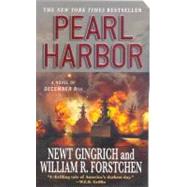

NEWT GINGRICH, former Speaker of the House, is the author of several bestselling books, including Never Call Retreat, Grant Comes East, and Gettysburg—all available from St. Martin’s Paperbacks. He is a member of the Defense Policy Board and co-chair of the UN Task Force, is the longest-serving teacher of the Joint War Fighting course for Major Generals, served in Congress for twenty years, and was Time magazine’s 1995 “Man of the Year.” He is also the founder of the Center for Health Transformation. He resides in Virginia with his wife, Callista. The Gingrich family includes two daughters, two sons-in-law, and two grandchildren.

WILLIAM R. FORSTCHEN, Ph.D., is a Faculty Fellow at Montreat College, near Asheville, North Carolina. He received his doctorate, with a specialization in military history, from Purdue University, and is the author of more than forty books. William is a pilot and currently flies an L-3, an original WWII recon plane. He resides near Asheville with his wife, Sharon, and daughter, Meghan.

Please visit www.newt.org/pacificwarseries.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.