Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

|

1 | (31) | |||

|

32 | (110) | |||

|

142 | (104) | |||

|

246 | (49) | |||

| Epilogue | 295 | (4) | |||

| Appendices | 299 | (8) | |||

| Acknowledgments | 307 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

The old tales of adventure, whose characters, from beginning to end, travelled over all the continents and sailed over all the seas, are now written no longer, because even children nowadays think them too unlike life; and yet one man still lives them through and through--the journalist.

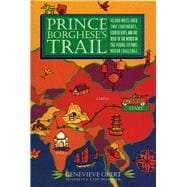

--Peking to Paris: Prince Borghese's Journey Across Two Continents in 1907

SAN FRANCISCO

[SATURDAY, MARCH 22]

The Golden Gate Bridge glowed in the crisp spring sunshine and white sails dotted the blue bay beyond the large window in Linda Dodwells posh living room. I had never met Linda before, and had only recently met the woman who was to be her co-driver on one of the greatest classic car rallies of all time.

I first spoke to the woman I'll call Karen the week before, at the annual potluck of the Arcane Auto Society, a loose-knit bunch of car devotees with a preference for odd automobiles. My husband Chris, our two children and I had been coming to these meetings for years. We had several arcane automobiles to choose from, but we usually drove either our baby-blue 1959 Fiat 500, or our 1955 Messerschmitt. Though the 'Schmitt, a three-wheeler that looks like an airplane cockpit without wings, attracts more attention, our little bubble-shaped Fiat is closer to our hearts, since we consider ourselves Fiat fanatics; we own and Chris runs a Fiat parts importing business and auto repair shop.

We pulled into the Arcane Auto Society's clubhouse and parked between two other micro-cars. On one side was a 600cc red-and-black Citroën 2CV, on the other a 300cc blue-and-white BMW Isetta, an egg-shaped car noted for its front-opening door. The Isetta belonged to Karen, who was talking to the 2CV owner about a new acquisition.

"I just bought a Zundapp Janus," she said.

"What's that?" the fellow said. "I've never heard of it."

She described it, and listening in, I remembered seeing one in a micro-car museum in Germany: it's a two-passenger four-wheeler, but the driver and passenger sit back-to-back. Its triangular shape makes it look like a miniature push-me-pull-you-mobile.

"I didn't think there were any of those in the States," I said, introducing myself. "I'm a freelance automotive journalist, and that car sounds like it would make a great story."

"Well, you're right, there aren't any in the States," Karen said. "Mine's still in England. But if you want to write a story, I've got a better one for you. Linda Dodwell and I are going to be driving from Beijing to Paris in the Second Peking to Paris Motor Challenge."

By some trick of synchronicity, I'd just read an article about the 1907 Peking to Paris race the week before. I'd been researching early auto races, sorting through reprints of old articles looking for women's names among the competitors. It was slow going, not because there weren't any women--in fact, there were many--but because I'd get so caught up in reading about those early races I'd lose track of time. In 1903, for example, Camille du Gast, reportedly the first woman racer, entered the Paris-Madrid. Halfway through, two drivers, three riding mechanics, and several spectators were killed in a series of accidents; Camille had been in eighth place until she stopped to assist a bleeding competitor. The 1907 Peking to Paris remarkably had no casualties, but it was the longest and toughest race of its day, and that reputation wasn't topped until the 1968 London to Syndey Marathon.

I couldn't pass up the chance to interview two women who would be participating in a re-creation of this great event. Karen and I set the interview date for the following Saturday.

After the potluck, I asked my librarian to dig a very old book out of storage: the tenth edition of Luigi Barzini's Peking to Paris: Prince Borghese's Journey Across Two Continents in 1907 . When she produced the worn volume, I took it home and finished reading it in two days.

By the time I met up with Linda and Karen in San Francisco, I was hooked. Somehow, some way, I had to be a part of their adventure.

* * *

In 1907, the automobile had only been around for twenty-one years. Those years were filled with a kind of mania that's difficult to imagine today--no contemporary innovation comes close to replicating the effect the automobile had on the world. Our current enthusiasm over the Internet, for example, is profound, but it's sedentary, intellectual. Not until someone invents Star-Trek-style "transporters" will anything come close to creating the kind of excitement the early automobile engendered.

Though the actual date is still argued along nationalist lines, it's generally agreed that Karl Benz's "vehicle with gasengine drive" qualifies as the first automobile, patented on January 29, 1886. The oft-quoted phrase says "The Germans invented the car, the French developed it, and the English opposed it," and Americans fell head-over-heels in love with it. In 1900, eight thousand passenger automobiles had been registered in the United States; by 1905, the number of registrations had increased nearly tenfold, to 77,000--nobody knows how many more were unregistered. In 1904, American author Edith Wharton wrote, "The motor-car has restored the romance of travel. Freeing us from all the compulsions and contacts of the railway, the bondage to fixed hours and the beaten track, the approach to each town through the area of ugliness created by the railway itself, it has given us back the wonder, the adventure, and the novelty which enlivened the way of our posting grandparents." Thanks to Henry Ford's egalitarian ideal of a motor-car for everyman, the automobile literally transformed America's way of life. The "Tin Lizzy" Model T, for example, put over fifteen million Americans on four wheels between its introduction in 1908 and the end of its run in 1927. In Europe, on the other hand, cars remained playthings for the rich until well past the First World War.

All nationalities, including the tradition-bound Brits, started racing motor-cars as soon as they got hold of them. The first formal race, called a "reliability trial" since race winners were always the cars that held together longest, was organized by a French magazine in 1894, and ran 127 kilometers (79 miles) from Paris to Rouen. The Tour de France began in 1899, and was won that year by a car averaging 35 mph over 1,350 miles. Hill-climbs pitted the early machines against gravity, and grim "dust trials" required a jury to stand by the road as cars roared by, then judge which car made them the dirtiest. Circular tracks sprung up all over, and city-to-city contests began between London-Brighton, Paris-Madrid, Paris-Berlin; then came the most audacious trek, the 1907 Peking-Paris.

In the article that appeared in Le Matin in January of 1907, the editors wrote:

The whole raison d'être of cars is that they make possible the most ambitious and unpremeditated trips to far horizons. For this reason the general public fails to see the logic of making motor-cars chase their tails in tight circles. We believe that the motor industry, the finest industry in France, has the right to claim a wider field in which to demonstrate its potential. Progress does not emerge from backing mediocrity or routine. What needs to be proved today is that as long as a man has a car, he can do anything and go anywhere.... We ask this question of car manufacturers in France and abroad: Is there anyone who will undertake to travel this summer from Paris to Peking by automobile? Whoever he is, this tough and daring man, whose gallant car will have a dozen nations watching its progress, he will certainly deserve to have his name spoken as a byword in the four quarters of the earth.

Some thirty entrants clamored to be that "tough and daring man." The start was set for mid-May, and based on the editors' estimated travel time of eighty-five days, the contestants would drive into Peking in the middle of August--monsoon season. So the direction was reversed, and Paris-Peking became Peking-Paris. The route was projected to traverse China's forbidding Western Mountains (between Peking and Mongolia), the Gobi Desert, and Siberia by way of a cart-track that had largely been abandoned, thanks to the recently completed Trans-Siberian Railway. By the end of March, when reports had come in from St. Petersburg and various outposts in China about the deplorable state of the roads, all but five entrants withdrew.

Among the five crews was a French con man named Charles Godard. Godard considered himself a professional driver, which in those days meant he drove motorcycles up a "Wall of Death" at circuses and traveling shows. He preferred to drive automobiles, but he hadn't yet found anyone who would loan him a car. The Peking to Paris, he decided, offered the perfect opportunity to prove himself to the world. He convinced a French manufacturer to list him as its driver, but that company soon pulled out of the event. Godard would not be thwarted so easily. He set to work on Josef Spijker, the Dutch manufacturer of Spyker Motor Cars. Godard convinced young Spijker that the cost of the 15HP model, and all the ancillary expenses, would be paid in full out of the proceeds of the ten-thousand-franc prize money Godard would collect when he won the race. Spijker agreed, and Godard then conned the merchant marine into shipping the car carriage-forward (cash-on-delivery). He ordered as many spare parts as the car could carry, then sold them all just before loading it onto the boat--he needed the proceeds to purchase his first-class ticket. His co-driver, Le Matin 's special correspondent Jean du Taillis, protested: "You can't set out on a journey like this without a sou . You can't do it!"

"Why not?" Godard answered. "Either I shall never see Paris again, or I shall come back to it in my Spyker, hot from Peking."

Joining Godard and du Taillis and their 15HP Spyker were nine other men in four other cars. Two teams of aristocratic French auto dealers would drive matching 10HP De Dion Boutons. A young Frenchman named Auguste Pons entered a 6HP Contal, a tiny one-cylinder "tri-car." The last and biggest car, a 40HP Itala, would be crewed by three Italians. The pilot was Scipione Luigi Marcantonio Francesco Rodolfo, Prince Borghese, Prince Sulmona, Prince Bassano, Prince Aldobrandini, the holder of four ancillary Italian dukedoms and four marquisates, a duke in the peerage of France, a grandee of Spain of the first class, a noble Roman and conscript, a patrician of Naples, Genoa, and Venice, and the grandson of the brother of Prince Camillo Borghese, who became Pope Paul V. Restrained, formal and clean-shaven in an era of luxurious moustaches, this man went by the less cumbersome name of Prince Scipio Borghese. His family had lost the bulk of their considerable fortune in the market crash of 1889, when Scipio was eighteen, so he enlisted in the army, which offered a "gentlemanly" income. There he developed a love of planning and organizing, and became somewhat of a socialist, unusual for a man with so many titles.

After he completed artillery school, Borghese's parents shipped him to France for diplomatic training, and also to find a wealthy and titled wife. He succeeded on both counts, but foreswore the foreign service in favor of breaking horses, climbing mountains, and planning long expeditions. In 1900, he traveled to Syria, Mesopotamia, Turkestan and Persia by horse, camel and foot, then followed the great rivers of Siberia--with occasional jaunts on the Trans-Siberian Railway--all the way to the Pacific. He wrote about this excursion, but his book wasn't like the popular travelogues of the day: it was a technical explorer's handbook. He considered himself a man of science, and he had a knack for reading a map in a single glance. He responded to Le Matin 's challenge as soon as he heard of it, ordered the Itala made to his specifications in February, and spent his thirty-sixth birthday examining detailed military maps of every inch of the presumed route. His brother, conveniently, was Italy's chargé d'affaires in Peking, and his wife had highly-placed relatives in Russia. While he knew Le Matin would arrange for basic supplies along the route, Borghese nevertheless contacted his wide network of relatives and friends to make sure additional stocks of petrol, food, and spares would meet him at frequent intervals.

Beside Borghese would be his riding mechanic Ettore Guizzardi, and behind him, perched on an extra fuel tank, would be Luigi Barzini, a journalist who had made his reputation as a foreign correspondent for Italy's Corriere della Serra and London's Daily Telegraph covering the 1904-05 Russo-Japanese War, and San Francisco's 1906 earthquake. When Barzini first met the mechanic, Guizzardi "was flat on his back under the Itala, lying quite still, with his arms folded. My first thought was that he was busy working. But he was relaxing. I discovered later that he was in his favourite place of off-duty pleasure. When there is nothing else to do he simply lies on his back under his motor-car and observes it, contemplates it item by item, every bolt and screw, in mystic communion with his machine."

Cars in those days were defined by their horsepower and their weight, using French terms, since the French (Peugeot and Panhard-Levassor) had been the first to build commercial motorcars: voitures were heavy cars, voiturettes were lighter cars, and mototris or motor-cyclettes were three-wheeled "tri-cars" or "cycle-cars." Steam and electric models abounded, but the gasoline-powered internal combustion engine was already proving its superiority. The most popular cars at the time were the mid-sized voiturettes, generally between eight and twenty horsepower and 3000 to 5000 cc's (though engine sizes sound similar today--for example, a Chevy Corvette displaces 5700 cc's or 5.7 liters--horsepower-per-cubic-inch has skyrocketed: that Chevy puts out 345 horsepower). The tri-cars or cycle-cars (precursors of our modern micro-cars) were much lighter and therefore needed much less power. Pons, in fact, boasted to his competitors that if the Chinese roads were truly as bad as everyone claimed, "the first to get through, perhaps the only one to get through, will be the Contal. Whenever you are stranded you can pick it up in your arms like a toy."

The voitures, on the other hand, needed much more power to propel their heavy frames. Borghese's Itala weighed 2700 pounds unladen, and two tons fully loaded. It was powered by a 7433cc four-cylinder engine that was expected to reach a top speed of 40 mph, very fast for the day. None of the cars had any kind of windshield. Their tops were cloth that dissolved soon after exposure to sun, wind or rain, and the shock absorbers were the passengers. There was no starter or electrical system of any kind; the brass headlight buckets would normally have been filled with candles, but some of the Peking-Paris raiders obtained newfangled carbide headlamps with built-in generators. Starting the cars each morning required manual cranking.

Godard's car was the closest in power to Borghese's--and the Spyker was lighter by 1200 pounds loaded--but those twenty-five extra horses made an immediate difference. Borghese took the lead right out of Peking.

All along the route, which followed the recently-installed telegraph wires, Luigi Barzini sent off dispatches to his two newspapers. These were reprinted in The New York Times, and his translated book was as big a hit in America as it was in Europe. The copy my librarian found for me ninety years later included a foreword by Luigi Barzini's son explaining the book's longevity. It had become something of a bible for young Italian men, proof of Italy's natural gift for world travel as direct descendants of Marco Polo, and their prowess as racers, from Borghese to Nuvolari to Ferrari and on. For the rest of the world, Barzini's book found a place on the shelf near Jules Verne, Edmund Hillary's tales of Everest and other stories of exotic places conquered by extraordinary men with (or without) fantastic machines.

In England, as in Italy, the Peking-Paris had remarkable staying power. One Briton, Allen Andrews, wrote what many consider a more rounded account than Barzini's (which, by virtue of Borghese's huge lead--he drove into Paris a full three weeks ahead of the rest--had given scant attention to the other teams). The Mad Motorists, published in 1965, featured the entertaining Godard as its main protagonist.

Just as Barzini's book had captured my imagination, Andrews' book changed the life of one Philip Young, a British motoring-journalist who had driven a Morris Minor in the first rally to traverse India, from Bombay up into India's Himalayas. Young later co-founded the Classic Rally Association, which organizes classic car rallies like the Monte Carlo Challenge. The first Monte Carlo Rally in 1911 created the term: competing cars started from points all over Europe and "rallied" at the finish line in Monte Carlo, Monaco. The CRA's Monte Carlo Challenge duplicates the earlier event for "classics," i.e., cars over twenty-five years old, every winter.

After reading The Mad Motorists, Young vowed to make the Peking-Paris happen again. Many had tried, including Luigi Barzini, Jr., but the Chinese, or the Russians, or myriad organizational problems, always prevented it. But not this time. Not if Young could help it.

* * *

I turned away from the radiant Golden Gate Bridge to focus on my two interview subjects, Karen and her co-driver, Linda Dodwell. Linda wore a soft black sweater and black jeans over a compact, powerful frame; she had blond, blunt-cut hair and striking blue eyes. A quick glance around the living room made it obvious that Linda's passion is motorcycling. Two detailed models of BMW motorcycles held pride of place directly in front of a framed photograph of her grown daughter, and the marque's blue, white and black emblem was stenciled on the side of her coffee mug and patched onto her black backpack. Cycling magazines were piled atop the coffee table where most women of Linda's social strata would display Town and Country and Vanity Fair . Phosphorescent issues of WIRED suggested computer literacy, and large black-and-white pastels on the walls revealed a taste for modern art.

She was evidently and proudly single, and unashamed to state her age: fifty-two. I soon learned that she was an artist (the pastels were her own), that this would be her first rally, classic or otherwise, and that she had very little knowledge of automobiles beyond what several good men-friends had shared with her. She had traversed Australia twice--she winters every year in Melbourne--once on a solo motorcycle journey and the second time with her daughter in a Toyota Land Cruiser. She figured that her trips around the world on BMW motorcycles--through Russia, India, South Africa and, of course, Europe--had provided adequate training for an event like the Second Peking to Paris.

While I talked with Linda, Karen sat quietly on the couch, saying little and seeming oddly uninterested in the conversation. At the potluck, Karen had been bubbly and talkative; now, she appeared distracted and uncomfortable. Beyond giving short answers to my questions, Karen acted as if she really didn't want to talk about this Peking to Paris thing. She looked away often, flipping through Linda's magazines and avoiding eye contact.

I was stunned at both women's ignorance of classic car racing and rallying. I had assumed that anyone entering something like the Second Peking to Paris Motor Challenge would be an experienced rallier, or at minimum a rally fan; he or she would want to campaign a long-owned, beloved automobile; that any two co-drivers would be very, very good friends--the kind who had traveled extensively together and knew each other's idiosyncracies--and that one or the other would be an excellent mechanic.

I was wrong on all counts. Linda and Karen had only met a few months before, brought together by mutual friends (two men) who had already signed up for the event. Karen did have a beloved marque, oddly enough the same as Linda's: BMW. But Karen's beloved Bavarians were Isettas. We joked about an Isetta making this long, difficult journey; though the Isetta's a four-wheeler, the rear wheels are placed only inches apart, so the car tracks like a tri-car. Auguste Pons had proved back in 1907 that the three-wheeled configuration put the vehicle at the mercy of every bump and pothole--even minor road-surface elevation changes stranded the Contal when the rear drive-wheel lost contact with the ground. Neither of them was seriously considering using one of Karen's Isettas for this journey.

Linda, remarkably, owned no car at all. She did have a car in mind, though. She had called the Classic Rally Association in England to ask if she could compete in a 1968 Toyota Land Cruiser. Philip Young told her that the four-wheel-drive Toyota "was not in keeping with the spirit of the event." He had recommended, instead, a Hillman Hunter. Neither woman had ever heard of it; I had heard of the British marque Hillman, but never the model name Hunter. They searched the Internet and discovered that the sedan, though not much to look at, was popular in England and Australia, and had made a name for itself back in 1968 when it beat out Porsches to win the London-Sydney. According to Young, the car had two additional advantages: it would be teamed with an identical car piloted by a British lord, and parts and mechanical expertise would be readily available in Iran, where the car is still being built as a "Peykan."

The two women hadn't yet decided if the Hillman would be right for them. I found it incredible that, with only six months until the starting line, they had yet to choose a car.

Both women professed some mechanical abilities, Linda with motorcycles and Karen with micro-cars, and they were both well-traveled. But the real reason they had decided to sign up was the route: it passed through China, Tibet, Nepal, India, Pakistan, Iran, Turkey, Greece, Italy, Austria, Germany and finally France. The road through Tibet is the highest in the world; Mount Everest's base camp would host an overnight. Seven days in the Islamic Republic of Iran would require that any women involved cover themselves from head to toe. I asked Linda and Karen if they were worried about this country's politics, and neither seemed concerned. "Iran's one of those places I wouldn't be able to see any other way," Linda said. Her main worries focused on health--everything from bacteria-laden food to the possibility of altitude sickness.

By the end of the interview, I realized that I was doing most of the talking, telling the women the history I knew of the original event, describing the vintage races I'd covered in California and Europe. I even admitted to the epic drive my now-husband and I took as teenage hippies--from central California to Alaska and back by way of western Canada, a four-month odyssey living in a 1959 Fiat Multipla. As I left, I promised to try and figure out a way to meet them en route, maybe in Kathmandu or Istanbul.

As I drove home in my ratty but reliable 1968 Fiat sedan--a car that, with some major suspension work, would be perfectly suited to the Peking to Paris Motor Challenge--I thought about the odd discomfort of the interview. Something about those two women bothered me, though I couldn't quite put my finger on what. It just didn't make sense: two women who hardly knew each other, spending ten thousand miles and forty-three days cooped up together in a thirty-year-old box they'd never seen before. Chris and I, for instance, would make a much more logical team. We're both certified car nuts; he's an excellent mechanic and driver, I'm a good navigator and decent driver, and we actually argue less on the road than we do at home. As I rounded the curves of the Santa Cruz Mountains highway, I kept thinking, if only we had forty thousand dollars for the fees and another twenty thousand to prep our Fiat. If only....

By the time I got home, I knew what it was that had been bothering me. "Those two women," I told Chris, "are going to kill each other long before they get to Beijing."

* * *

Two days later, my e-mail box held two messages. "Please call me!" was the subject of the first, and "Sad news" headed the other, originating from an e-mail address I didn't recognize. "Call me" said simply "Can you give me a call sometime soon? It's about the rally ... I can't find your card, Thx Karen."

"Sad news" was longer.

Dear Gennie, Jenny, Genny? (sp)

This is to inform you that after much consideration I have decided to move on with the Rally project without Karen. You don't need to know the particulars ... just say I have decided to go with my intuition. It is not my style to renege on a commitment, but in this case I have reason to believe we were not a good match. She is very angry with me and is hoping I will change my mind. This will not happen. I have decided I will take my chances with losing out myself knowing I have made the right decision at this time.

I don't know how this affects you since I'm not clear how you are connected with Karen. I did get the impression that if you could figure out a way to participate you would be very interested. If you feel comfortable talking about that with me I will be glad to hear from you. If you decide not to get involved I will certainly understand.

All the best,

Linda

I printed this one out and showed it to Chris. "Do you think she's actually inviting me to go with her?" I asked him.

"You can't afford it."

"I know, but can't I dream a little?" I clicked Reply and wrote a response, halfheartedly suggesting some women I knew as possible replacements, mentioning how much I'd love to myself, if only. A phone call came the next day.

"I have a feeling about you," she said. "I think it might work out."

I parroted Chris. "I can't afford it."

"If that's your only problem," she said, "I think we can work something out."

I held the phone out and stared at the receiver. "Really?" I finally asked, squeaking like a pre-teen girl who's just been offered a pony. We talked and talked, brainstorming ideas on how to find sponsors. By the end of the conversation it seemed as if we were old friends. "Give me a couple of days to talk to my family," I told her. "I'll come up Thursday. We can talk in person."

I was shaking when I hung up. I walked barefoot over the jagged gravel in our long driveway--too excited to put on my sandals--to our garage barn, where Chris labored over the engine of a Fiat Spider he hoped to sell.

"You can't afford it." He didn't even look up from the head he was re-torquing.

"Maybe if I can get a sponsor ..."

"It's a long time to be away. Who's supposed to take care of the kids?" His bushy eyebrows shot up and his head lifted just enough to see me.

I tried to stand still, but I felt like I was vibrating, shivering in the full sun. "I know. I don't know. You, maybe, with some help from Mom ..."

"Your mother? " He stepped out of the barn, and began walking toward the house. I followed. "You want me to take care of the kids and deal with your mother while you drive halfway around the world?"

"It's a long shot that I'll even get sponsorship. But I'd like to try." He kept walking. "Look at it this way," I pleaded. "What would you say if a guy asked you?" He stopped, looked down at the ground, then at his grease-blackened fingernails, then at the sky. He heaved a big sigh: air rushed out of him, as if he'd flicked the switch on his air compressor.

"You're right," he said, and walked silently into the house.

* * *

I spent the next few days poring over the brochures Linda had given me. I lingered long over the day-to-day route descriptions. For September 7 it read, "Zhang Jiakou to West Baotou, 507 kms. A longer day, into Inner Mongolia, along the southern edge of the Daqing mountain range, towards the great Yellow River. Northern China is fairly industrious, we do our best to choose the quietest roads." Six days later would be "Golmud to Tuotuoheyan, 439 kms. Golmud marks the start of the `Roof of the World' section. Although mainly tarmac, the road across the plateau is constantly being repaired because of the severe weather conditions and diversions and delays are to be expected. Ground clearance is important on this section. First there is the long steep climb up to the Kunlun Pass (16,000 ft). The scenery is awe-inspiring with expanses of snow and moorland pierced by numerous peaks. Tuomoheyan is an army garrison on the Tuotuo River, one of the major tributaries of the Yangtze."

The more I read, the more convinced I became that there are two kinds of people: those who read something like this and think "Oh my God! How arduous! I'd never want to deal with all that"; and those who, like me, like Linda, simply say, "Sign me up."

Copyright © 1999 GENEVIEVE OBERT. All rights reserved.