Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

| ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS | xi | ||||

| MAP OF IRAN | xiii | ||||

|

1 | (9) | |||

|

10 | (32) | |||

|

42 | (45) | |||

|

87 | (31) | |||

|

118 | (39) | |||

|

157 | (24) | |||

|

181 | (25) | |||

|

206 | (51) | |||

|

257 | (20) | |||

| 10 Ashura | 277 | (4) | |||

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 281 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Why, I wondered long ago, don't the Iranians smile? Even before I first thought of visiting Iran, I remember seeing photographs of thousands of crying Iranians, men and women wearing black. In Iran, I read, laughing in a public place is considered coarse and improper. Later, when I took an oriental studies course at university, I learned that the Islamic Republic of Iran built much of its ideology on the public's longing for a man who died more than thirteen hundred years ago. This is the Imam Hossein, the supreme martyr of Shi'a Islam and a man whose virtue and bravery provide a moral shelter for all. Now that I'm living in Tehran, witness to the interminable sorrow of Iranians for their Imam, I sense that I'm among a people that enjoys grief, relishes it. Iran mourns on a fragrant spring day, while watching a ladybird scale a blade of grass, while making love. This was the case fifty years ago, long before the setting up of the Islamic Republic, and will be the case fifty years hence, after it has gone.

The first time I observed the mourning ceremonies for the Imam Hossem, I was reminded of the Christian penitents of the Middle Ages, dragging crosses through the dust and bringing down whips across their backs. In modern Iran, too, there is self-flagellation and the lifting of heavy things -- sometimes a massive timber tabernacle to represent Hossein's bier -- as an expression of religious fervour. The Christian penitents were self-serving; calamities such as the Black Death provoked a desire to atone, to save oneself and one's loved ones from divine retribution. Iran's grieving does not have this logic. This is no act of atonement, but a sentimental memorial. Iranians weep for Hossein with gratuitous intimacy. They luxuriate in regret -- as if, by living a few extra years, the Imam might have enabled them to negotiate the morass of their own lives. They lick their lips, savour their misfortune.

I see Hossein alongside Tehran's freeways, his name picked out in flowers that have been planted on sheer green verges. I see his picture on the walls of shops and petrol stations, printed on the black cloths that are pinned to the walls of streets. The conventional renderings show a superman with a broad, honest forehead and eyes that are springs of fortitude and compassion. A luxuriant beard attests to Hossein's virility, but his skin is radiant like that of a Hindu goddess. He wears a fine helmet, with a green plume for Islam, and holds a lance. I once asked an elderly Iranian woman to describe Hossein's calamitous death. She spoke as if she had been an eyewitness to it, effortlessly recalling every expression, every word, every doom-laden action. She listed the women and children in Hossein's entourage as if they were members of her own family. She wept her way through half a dozen Kleenexes.

Every Iranian dreams of going to the town of Karbala, the arid shrine in central Iraq that was built at the place where Hossein was martyred. I went there myself, the camp follower of American invaders, and visited the Imam's tomb. Inside a gold plated dome, Iraqis calmly circumambulated a sarcophagus whose silver panels had been worn down from the caress of lips and fingers. They muttered prayers, supplications, remonstrations. Suddenly, the peace was shattered by moans and the pounding of chests, splintered sounds of distress and emotion. Five or six distraught men had approached the sarcophagus. One of them was half collapsed, his hand stretched towards the Imam; the others shoved and slipped like landlubbers on a pitching deck. My Iraqi companion curled his lip in distaste at the melodrama. 'Iranian pilgrims' he said.

It all goes back to AD 632, when the Prophet Muhammad died and Ali, his cousin and son-in-law, was beaten to the caliphate, first by Abu Bakr, the Prophet's father-in-law, and then by Abu Bakr's successors, Omar and Osman. Ali gave up political and military office, and waited his turn, and the modesty and piety of the Prophet's time was supplanted, according to some historians, by venality and hedonism. After twenty-five years, following Osman's brutal murder, Ali was finally elected to the caliphate. But his rule, although virtuous, lasted only until his murder five years later and gave rise to a rift between his followers and Osman's clan, the Omayyids. The origin of the rift was a dynastic dispute, between supporters of the Prophet's family, represented by Aji, and the Prophet's companions, represented by the first three caliphs. It prefigured a rift that continues, between the Shi'as -- literally, the 'partisans of Mi' -- and the Sunnis, the followers of the Sunnah, the tradition of Muhammad.

After Mi's murder, Hassan, his indolent elder son, struck a deal with the Omayyids. In AD 680 Hassan died and Al's younger son, Hossein, took over as head of the Prophet's descendants. Hossein was pious and brave and he revived his family's hereditary claim to leadership over Muslims. This brought him into conflict with Yazid, the Omayyid caliph in Damascus. When the residents of Kufa, near Karbala, asked Hossein to liberate them from Yazid, the Imam went out to claim his birthright, setting in train events that led to his martyrdom.

One night, on the eve of the anniversary of Hossein's death, I put on a borrowed black shirt and took a taxi to a working-class area of south Tehran. The main road where the taxi dropped me was already filling with families and men leading sheep by their forelegs. Cauldrons lay by the side of the road. Everyone wore black; even the little girls wore chadors, an unbuttoned length of black cloth that unflatteringly shrouds the female body. I entered a lane with two-storey brick houses along both sides. There was a crowd at the far end of the street, their backs to us, and their silhouettes were flung across the asphalt. Black bunting had been strung between lampposts ...

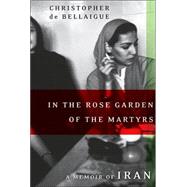

In the Rose Garden of the Martyrs

Excerpted from In the Rose Garden of the Martyrs: A Memoir of Iran by Christopher de Bellaigue

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.