Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

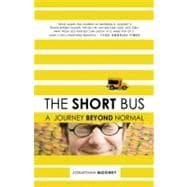

Jonathan Mooney graduated from Brown University with an honors degree in English. A recipient of the Truman Fellowship for graduate study in creative writing and disability studies, he is also the co-author of Learning Outside the Lines.

| Prologue: The Short-Bus Story | p. 1 |

| Everyone in Their Right Place | |

| You Are Responsible for the Safe Operation and Cleanliness of This Vehicle | p. 15 |

| The Lightning Field | p. 30 |

| The Hole in the Door | p. 42 |

| Steel Boxes, Crushed Cars | p. 57 |

| The Sound of One Hand Clapping | p. 68 |

| Welcome Pest Controllers Association | p. 91 |

| How to Curse in Sign Language | p. 106 |

| I Don't Know, I Don't Remember, It Doesn't Seem to Matter Anymore | p. 123 |

| Burning Man | |

| I Can't Remember to Forget You | p. 133 |

| The Turnaround Dance | p. 146 |

| Big Things, Little Things | p. 167 |

| Katie's Book of Life | p. 180 |

| Black Rock City's Bell Tree | p. 201 |

| The Eccentrics | |

| Driftwood Beach | p. 221 |

| Things Not to Share-at First | p. 233 |

| What Is Left, After What One Isn't Is Taken Away, Is What One Is | p. 258 |

| Author's Note | p. 269 |

| Acknowledgments | p. 271 |

| Table of Contents provided by Ingram. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Excerpted from The Short Bus: A Journey Beyond Normal by Jonathan Mooney

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.