Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

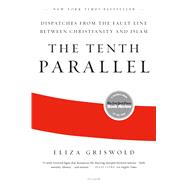

Eliza Griswold, a fellow at the New America Foundation, received a 2010 Rome Prize from the American Academy in Rome. Her journalism has appeared in The Atlantic, The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, and Harper’s Magazine, among others. A 2007 Nieman Fellow at Harvard University, she was awarded the first Robert I. Friedman Award for investigative reporting. A collection of her poems, Wideawake Field, was published by FSG in 2007.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.