| Acknowledgments | ix | ||||

| Chronology | xi | ||||

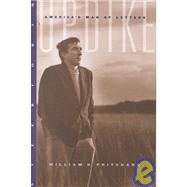

| Introduction: The Man of Letters | 1 | (16) | |||

|

17 | (28) | |||

|

45 | (18) | |||

|

63 | (54) | |||

|

117 | (28) | |||

|

145 | (24) | |||

|

169 | (26) | |||

|

195 | (34) | |||

|

229 | (24) | |||

|

253 | (24) | |||

|

277 | (24) | |||

|

301 | (32) | |||

| Notes | 333 | (6) | |||

| Bibliography | 339 | (4) | |||

| Index | 343 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

FIRST FRUITS

The Carpentered Hen • The Poorhouse Fair • The Same Door

Updike's first three published volumes -- a book of poems, a novel, and a collection of stories -- were written over a five-year period, 1954-9, although he reached back into the Harvard Lampoon for two poems published in 1953. Each of these books received respectful, "positive" notices, but their collective impact was minor compared to that of a predecessor like Salinger ( The Catcher in the Rye , 1951) or of his contemporary Philip Roth, who made his debut in 1959 with the prizewinning Goodbye, Columbus . Updike's earliest books didn't set out, so it seems, to make major claims for themselves: full of style, they might well be called "stylish," a word with just the hint of a reservation about it. The poems, almost entirely light verse, are undeniably clever, but then -- so the reservation says -- perhaps too clever, merely cute. The novel, in its determination to avoid the autobiographical sprawl of a first book, is compact, elusive, often oblique in its presentation. The stories present graceful, unfervid renderings of people in very much less than extreme circumstances -- in a high-school classroom, at the dentist, on a New York City bus, or returning to see old classmates at a high-school party.

With hindsight and knowledge of the forty-year career of books about to unfold, however, we can say that Updike's first three showed a writer who was concerned to demonstrate more than one string to his bow. Although the strings have intimate relations with one another, individually they exhibit different sides of an inclination and temperament. The Carpentered Hen ( "And Other Tame Creatures" is the subtitle) exhibits Updike the "gagster," as he once called himself: the cartoonist in print, the former Lampoon editor whose specialty, he tells us in an interview, was Chinese jokes in which children at a birthday party sing "Happy Birthday, Tu Yu," or "coolies" listening to a labor agitator ask one another, "Why shouldn't we work for coolie wages?" In the stories from The Same Door the gagster is subdued; a single character is observed in relation to other characters and placed by an ironic narration whose voice is quieter, woven into a subtler texture. By contrast with these straightforward ways of address to a reader, the narrative of The Poorhouse Fair is impersonal, almost disembodied, fully caught up in the elaborate patterns of image and perception that inform the novel's sentences. In the spirit of Holden Caulfield's formulation in The Catcher in the Rye , one might (if one were Holden, certainly) phone up the light-verse writer or the author of the stories for an animated conversation, but one would not be at all inclined to dial the creator of the novel.

It may be too easy to credit Updike with supreme canniness in distributing his three earliest eggs in baskets distinct from one another, yet together they stake out a claim for a writer who fancied himself, from the beginning, at least a triple threat. In their different ways each book avoids falling into the blatantly autobiographical plea of an "I"-dominated young man making his debut. Updike declares himself, but does so by also keeping a lot back. In one of his letters Robert Frost speaks satisfiedly of having a "strong box" of poems he's written but not yet published: "I have myself all in a strong box where I can unfold as a personality at discretion," he wrote. Updike might be said to have "had" himself this way as well, though he didn't bother to boast about it. These books called forth words from reviewers that would stick to him throughout his career: elegance, charm, wit, gracefulness, verbal talent -- the stuff that made up "a writer's writer." This is of course a dangerous thing to be called, perhaps especially when one is starting out, for it is but a step away from the suggestion, first made by Norman Podhoretz in 1964, that one has nothing to say.' A writer's writer deals in words rather than things, art rather than life; his art shows itself ostentatiously as embroidery, astutely stitched but cloying in its richness. "Clever" quickly modulates into too clever, merely clever, clever at the expense of worthier things for a writer to be. What such predictable and not very imaginative responses ignore -- or simply aren't able to conceive -- is the boldness that lies in unrepentantly making language a display of self, rather than hiding that self behind more modest appearances. The young Updike inhabited his lines and sentences in ways that were audacious, provocative, extravagant. If, from the beginning, he was a writer's writer, that makes him all the more difficult to come to terms with -- after all, the poet's poet, Edmund Spenser, still presents a problem for readers.

The Carpentered Hen

It may seem odd to launch an account of Updike's career as man of letters with his early light verse. But he has noted, in the preface to Collected Poems (1993), that this way of "cartooning with words" first got him into print, in the work for his hometown papers and the Harvard Lampoon that preceded his first published volume. In retrospect Updike's way of dividing his light verse from his "poems" was intended to say that the poems derived from the "real (the given, the substantial) world," while light verse "took its spark from language" and came "from the man-made world of information -- books, newspapers, words, signs." He did not attempt to conceal light verse's derivation from verbal sources; many of the poems in The Carpentered Hen as epigraph a line picked out of a newspaper, a magazine, a sign in a bus. "Youth's Progress," for example, was sparked by some words from Life magazine that occurred, doubtless, in one of its reports of goings-on in American colleges: "Dick Schneider of Wisconsin ... was elected `Greek God' for an inter-fraternity ball." Updike duly celebrates the lad in three stanzas:

When I was born, my mother taped my ears

So they lay flat. When I had aged ten years,

My teeth were firmly braced and much improved.

Two years went by; my tonsils were removed.

At fourteen, I began to comb my hair

A fancy way. Though nothing much was there,

I shaved my upper lip -- next year, my chin.

At seventeen, the freckles left my skin.

Just turned nineteen, a nicely molded lad,

I said goodbye to Sis and Mother; Dad

Drove me to Wisconsin and set me loose.

At twenty-one, I was elected Zeus.

The low-key, modest, and rather toneless account by the young man of how he was shaped into divinity exists only to usher in that closing apotheosis, locked into placed by strongly rhymed couplets (the difference to the eye of "loose" and "Zeus" is also part of the fun). Doubtless Updike could have provided an accompanying graphic cartoon, but the words do well enough on their own.

Kingsley Amis, who chose and edited The New Oxford Book of English Light Verse , wrote a valuable introduction to it in which he called light verse altogether literary and artificial, a kind of performance that caters to certain expectations in its audience. Its task is to emphasize "manners, social forms, amusements, fashion (from millinery to philosophy), topicality, even gossip," and to treat these matters always in "a bright, perspicuous style." One of the ways Amis distinguished light from what he called "high" verse is that in the latter, as with a concert pianist, a wrong note here or there was permissible; with light verse, the writer -- like a juggler -- must not drop a plate. This caveat applies to the tight prosodic control necessary to good light verse, and the one spot where "Youth's Progress" strikes a slightly wrong note is its penultimate line ("Dad drove me to Wisconsin and set me loose"), where the extra syllable causes a falter in the middle -- hardly as notable, though, as a juggler's plate dropping.

In his 1982 foreword to the reissued Carpentered Hen , Updike noted that many of the poems were written during the year he spent, after graduating from Harvard, on a fellowship in Oxford at the Ruskin School of Art, and that the details triggering the poems -- such as the line from Life about Dick Schneider's deification -- took on quaintness from an overseas perspective. In the same foreword he locates his endeavors in a tradition that latterly included such American light-versers as E. B. White, Phyllis McGinley, and Morris Bishop. Today's reader may well find those names stone dead, along with the poems they produced; but in the 1950s and a way beyond, the light-verse industry enjoyed a relative boom. Books by its practitioners were reviewed in the New York Times Book Review , the general sense being that, in the age of Eliot and Wallace Stevens, it was an excellent alternative to high modernism. For that very reason I remember setting myself resolutely against light verse and its advocates, making sure I did not find in their productions the "superior amusement" T. S. Eliot said was poetry. Looked back on from forty years, Updike's light verse appeals partly because of its period furniture: poems, for instance, about what Debbie Reynolds and Eddie Fisher did on their whirlwind honeymoon, or a Life article about the tribulations of the starlet Kim Novak. But sometimes a mere word is enough to strike off a sequence that builds in surprise and delight -- as happens in "To an Usherette":

Ah, come with me,

Petite chérie ,

And we shall rather happy be.

I know a modest luncheonette

Where, for a little, one can get

A choplet, baby lima beans,

And, segmented, two tangerines.

Le coup de grâce

My pretty lass,

Will be a demi-demitasse

Within a serviette conveyed

By weazened waiters, underpaid,

Who mincingly might grant us spoons

While a combo tinkles trivial tunes.

Ah, with me come,

My mini-femme

And I shall say I love you some.

This homage to the diminutive is a perfect instance of what its creator, in the same foreword, called light verse's "hyperordering of language through alliteration, rhyme, and pun." It was a "way of dealing with the universe," he said, that partook of high spirits. For the reader, as well as, doubtless, the writer, such an exercise generates a purely literary pleasure that has in it a strong element of admiration -- of wondering at the spirited facility brought to bear on the usherette and her related items.

Updike observed that it was around 1964, after the Kennedy assassination, when he found the market for light verse drying up. Although he didn't himself cease to write it, the practice became more and more occasional for him -- an exception rather than the rule of his poetry composition. It is also of interest that these early evidences of high spirits were thrown off by a sensibility which, at its opposite end, concerned itself with thoughts about God, immortality, the soul. The composer of light-verse squibs was also a man whose reading in Kierkegaard, Karl Barth, and other soul-doctors was no disinterested game but one played for ultimate stakes.

The Poorhouse Fair

When Updike and his family returned in 1955 from the year at Oxford, they settled in New York City, he having been hired by Katharine White to provide "Talk of the Town" columns and other contributions to the New Yorker . Sometime in 1956 he completed a draft of a six-hundred-page novel titled Home , but decided against further revising it and gave his attention instead to the poems and stories he was writing and publishing in the magazine. In 1957, with a second child on the way, he and Mary decided to move to New England, his determination being to function as a self-employed, self-supporting writer. The decision may have helped to concentrate composition of a relatively short novel, very different in focus and narration from the abandoned one; at any rate, The Poorhouse Fair was written in three months after the move to Ipswich, Massachusetts. When Harper Brothers, which had brought out The Carpentered Hen , expressed dissatisfaction with the novel's ending, Updike changed publishers to Alfred Knopf, beginning -- when Knopf published The Poorhouse Fair in 1959 -- the mutually gratifying association that has endured ever since.

By far the most interesting commentary on The Poorhouse Fair came from its author twenty years after the writing of the book when, in an introduction to the 1977 edition, he provided a rationale for its futuristic setting and named a few books and writers instrumental to its conception. The novel had its roots, he tells us, in a 1957 visit to Shillington in which he inspected the site of the former County Home, a yellow "poorhouse" at the end of the street where he had lived. He decided to write a novel in celebration of the fairs held at that institution during his childhood, and in conceiving the book's central figure, a ninety-four-year-old inmate named John Hook, he would pay tribute to his recently deceased maternal grandfather, John Hoyer. The novel's time is set roughly twenty years hence, not really a long jump ahead compared to other examples of the futuristic genre. Orwell's 1984 had been in Updike's mind: there is, in The Poorhouse Fair , a disposition of countries reminiscent of the tripartite division in Orwell's totalitarian world. But in Updike's novel, totalitarian is hardly the adjective for the benignly intended administration of Conner, the prefect whose attempts to preside efficiently and thoughtfully over the old people's declining years go awry.

More important than Orwell's novel for the literary texture of The Poorhouse Fair were the examples of two other English writers: H. G. Wells's science fiction classic "The Time Machine," and a not very well-known futuristic novel by a writer Updike would more than once admire in print: Henry Green's Concluding (1948). Both writers are invoked in the 1977 introduction for their stylistic distinctiveness: singling out the "superb and dreadful poetry" of "The Time Machine," Updike names an aspect of Wells's work that is typically ignored by critics concerned with themes and ideas. With Henry Green, Updike admits to appropriating from Concluding an "embarrassing" number of particulars; he acknowledges also the influence of Green's "wilfully impressionist style" by quoting from the opening paragraph of Concluding , then following it with early sentences from The Poorhouse Fair . It's hard to see why the extremely mannered English writer held so much attraction for the American, but it is useful to be directed, at the novel's outset, to the way typical sentences from The Poorhouse Fair conduct themselves:

In the cool wash of early sun the individual strands of osier compounding the chairs stood out sharply; arched like separate serpents springing up and turning again into the knit of the wickerwork. An unusual glint of metal pierced the lenient wall of Hook's eyes and struck into his brain, which urged his body closer, to inspect. Onto the left arm of the chair that was customarily his in the row that lined the men's porch the authorities had fixed a metal tab, perhaps one inch by two, bearing MR, printed, plus, in ink, his latter name.

This is both cool and arresting, by not nudging us into an easily remembered impression -- as who should say, oh yes, I've noticed how, in wickerwork, strands of osier arched like serpents spring up -- but inviting us to recognize the poet's eye as Emerson named it at the beginning of Nature : "There is a property in the horizon which no man has but he whose eye can integrate all the parts, that is, the poet." Such seeing is some way beyond our ordinary, finite procedures.

Thus one understands why a stylist like the New Yorker jazz critic, Whitney Balliett, should have written an admiring review of The Poorhouse Fair . Balliett praised Updike's prose as "tight but never brittle ... breaded with simile and metaphor," also his "tough, hounding selectivity of materials," an especial characteristic of poetry. Such a prose was like what Balliett was writing so well in his descriptions of a comet solo by Bix Beiderbecke or one of Sid Catlett's drum riffs. Hook's discovery of the metal tags Conner has had placed on the inmates' chairs -- a trivial example, but one that quickly establishes the kind of officious care (for their own good) being provided them -- is negotiated in a language Hook himself, like the rest of us, would not employ, as in the detail of the metallic glint piercing "the lenient wall of Hook's eyes," thus urging his body closer. Such language has its hand in making the book feel strangely remote, and Balliett himself mentioned that he never thought of either "liking" or "disliking" it. Its remoteness is part of our relation even to the main character, Hook, who again sees with a poet's eye as he looks eastward over farm plains to the New Jersey hills:

Despite the low orange sun, still wet from its dawning, crescents of mist like the webs of tent caterpillars adhered in the crotches of the hills. Preternaturally sensitive within its limits, his vision made out the patterned spheres of an orchard on the nearest blue rise, seven miles off.

Hook goes on seeing the landscape, through a long paragraph, and even though he's been familiar with it for a long time, his perceptions are surely extraordinary ones for a ninety-four-year-old ("webs of tent caterpillars adhered in the crotches of the hills"). But we acknowledge Updike's writerly hand in all this: as with the verbal high jinks of his light verse, this novel's prose calls attention to itself and makes a demand on readers some were -- and are -- unwilling to meet.

The disposition of narrative action in The Poorhouse Fair is as coolly detached as the behavior of individual sentences. Its 185 pages are divided into three untitled sections, which are subdivided into forty parts, separated one from another by extra space. There are no chapters: we move from one character's perspective to another's, and as the book proceeds the cross-referencing becomes intricate, often pleasurable. What happens is always tame, never the stuff of tragedy, nothing that would be amiss in a novel by Howells. We are told of the physical appearance of quilts, readied for sale at the fair; what to do with a half-dead cat that suddenly materializes; a trip to the infirmary by an inmate with an inflamed ear; a parakeet on the loose; a delivery truck that knocks down part of the poorhouse's surrounding wall as it attempts to deliver soft drinks for the festivities. These less-than-momentous events are presented in a narrative voice devoid of anything, it seems, but the obligation to set them down clearly, distinctly, and with nuance. So in those rare moments when the voice deepens and moves inward -- mainly when Hook is the focus -- the narrative temperature makes a pronounced rise. For a moment we glimpse a different kind of book.

Here is Hook, having been confronted with some frank sentiments about death by one of the female inmates he's been conversing with, and now attempting to regain his composure:

Her speaking so plainly of death stirred the uglier humors in him. In the mid-mornings of days he usually felt that he would persist, on this earth, forever; that all the countless others, his daughter and son among them, who had vanished, had done so out of carelessness; that if like him they had taken each day of life as the day impossible to die on, and treated it carefully, they too would have lived without end and would have grown to have behind them an endless past, like a full bolt of cloth unraveled in the sun and faded there, under the brilliance of unrelenting faith.

This touches momentarily on a conceit most of us have entertained, superficially plausible and immensely reassuring. Such a moment is as close as we ever get to Hook's thoughts or those of any other character; by contrast, Conner (as Updike himself notes in the introduction) comes across mainly as a thirty-year-old "goodie-goodie" who "should have been something more." (Curiously enough -- and who knows how much to make of it? -- the paragraph succeeding Hook's deep thoughts about life and death suddenly registers, in the meadow beyond the wall, a rabbit pausing, "a silhouette of two humps, without color." Hook's creator may already have been making plans to get the rabbit running.)

Moments of poetically rendered vision like this stand at one extreme of narrative style, the opposite of which is the prosing of banal talk, the stuff of daily conversation at the poorhouse. At the midday meal on fair day, a large one (meat loaf, boiled potato, broccoli), Mrs. Lucas, married to the man with the earache, expatiates on the difficulties of caring for a parakeet her daughter has unloaded upon her and which, let out of its cage for an airing, has escaped through the door suddenly opened by Mr. Lucas. Mrs. Lucas bitterly retails her daughter's thoughtlessness:

"She bought it for her boy and the boy tired of it after a week, as you might expect. So, ship it off to Mom, and let her spend her pitiful little money on fancy seed of all sorts and cuttlebone. Let her clean the cage once a day. Let her worry with the bird's nails. They're more than a half-circle and still growing. It gets on its perch and tries to move off and beats its wings and wonders why it can't, poor thing. I thought I could take my sewing scissors and trim its nails myself; they're fragile looking; you can see the little thread of blood in there. But evidently you can't. They'll bleed unless you know just where to cut."

And on and on. A bit like one of Miss Bates's endless monologues in Emma , but also rather extraordinary when considered from the perspective of the young first novelist who, among other tasks, has set himself to imagine trivial anxieties of old age as embodied in the hazards of parakeet pedicure. This is the kind of challenge Updike courted in writing The Poorhouse Fair : that of vocalizing, in the most unremarkable speech rhythms, the dismal complaint of a boring old lady. And it is why the novel benefits, even more than most novels do, from rereading. Once you know how it comes out -- or doesn't come out, since the ending is impressionistically inconclusive -- you begin to pay attention to something other than story or idea; to the textures, the all-too-human polyphony that informs the book.

On rereading, we're likely to pay less attention to the futuristic paraphernalia which, important as it was in Updike's motive for writing the novel, is much less so in our experience of it. Setting a book twenty years in the future is a relatively modest leap (think, by contrast, of Wells's "The Time Machine") and feels even less breathtaking as we read it in 2000. In fact I think The Poorhouse Fair is least convincing when it presses hard the thematic content of a future America, even though there are good formulations along the way ("Heart had gone out of these people; health was the principle thing about the faces of the Americans"). An anonymous voice declares, late in the book, that with the disappearance of war -- a pact has been made with the "Eurasian Soviet"--

we were to be allowed to decay of ourselves. And the population soared like diffident India's, and the economy swelled, and iron became increasingly dilute, and houses more niggardly built, and everywhere was sufferance, good sense, wealth, irreligion, and peace.

This anonymous narrative, in its sweep of declaration, is less convincing and engaging than when similar sentiments are expressed directly through the consciousness of Hook, especially when he muses, commandingly, on the American past: "There is no goodness, without belief. There is nothing but busy-ness. And if you have not believed, at the end of your life you shall know you have buried your talent in the ground of this world and have nothing saved, to take into the next." But the resonance this has is independent of the novel's futuristic dimension.

There is also an increasingly allegorical feel to things as the novel draws to its close. The most notable piece of action comes at the moment when, repairing the stone wall hit by the soft-drink truck, some of the inmates, though not Hook, in a parody of the stoning of the martyr Stephen, throw stones at Conner, wounding his pride and soul. Conner declares, "I know you all," and tells his sidekick Buddy that he "forgives" them, whatever that means. The poorhouse itself, as the townspeople come to the fair, assumes a larger symbolic range of perspective: "In a sense the poorhouse would indeed outlast their homes. The old continue to be old-fashioned, though their youths were modern. We grow backward, aging into our father's opinions and even into those of our grandfathers." That last sentence is delivered very much in the voice of an Updike we shall become increasingly familiar with in fiction to come. Here, though eloquent, it feels just a shade disembodied, almost too wise for the occasion.

In a later comment on the book Updike said, unpacking the metaphor of his novel, that the poorhouse was our world, a poor house to live in, under the aspect of the spirit, but nevertheless all we had, and to be cherished for that fact. There is an appealing inconclusiveness to the way things are concluded in the novel: the narrative diffuses itself into myriad voices of the visitors -- separate, random bits of conversation that overall, as to be expected, are aimless, casual. Hook, ending his day, and one day closer to the end of his life, thinks vaguely about how he must try to help Conner after the day's humiliation -- must tell him something "as a bond between them and a testament to endure his dying in the world." But the book's final sentence is a question: "What was it?"

The Same Door

There is comparatively little of such tentativeness in the sixteen stories published in the New Yorker between late 1954 and the beginning of 1959 and collected in The Same Door . Updike's first collection of short fiction came at the end of a decade that had seen a number of impressive collections by American writers, among them Salinger's Nine Stories (1953), John Cheever's The Enormous Radio (1953), and Flannery O'Connor's A Good Man Is Hard to Find (1955). More than one critic has noted the air of self-conscious effort with which short-story writers try to say what it is that this genre attempts and what claims it makes on a reader. Such an effort is noted by John Bayley, in his study of the short story from Henry James to Elizabeth Bowen, when he quotes Kay Boyle, herself a prolific writer of stories who attempted to put it all into words: "At once a parable and a slice of life, at once symbolic and real, both a valid picture of some phase of experience, and a sudden illumination of one of the perennial moral and psychological paradoxes which lie at the heart of la condition humaine ." Bayley remarks wittily that this definition makes the perusal of a short story into more of a duty than a pleasure, and we may sympathize with his uneasiness. No such anxiety is shown, he points out, by writers of novels, who don't have to feel that they must justify their trade, whether the result is a tight, poetic operation like The Poorhouse Fair or a loose and baggy monster. Certainly Boyle's solemn claim, that stories render the human condition (in French), feels inappropriate to characterize the playful, unsolemn treatment of characters and situations in Updike's early ones.

Although the category has fallen out of use, a popular way of classifying and often dismissing or disparaging short fiction, especially in the 1950s and 1960s, was to attach the adjective New Yorker to it. New Yorker stories were supposedly deft, witty, but superficial (perhaps therefore superficial) treatments of eastern-seaboard suburban life as lived by well-off, middle-class families and as written about predominantly by American middle-class white males like Salinger, Cheever, and Updike. Characters in these stories were wholly under the author's thumb; the only disruptions allowed them were minor ones, to be remedied or absorbed by the story overall. The "typical" New Yorker product was narcissistic in its overriding concern for style, which rendered all action in neatly turned, elegant sentences and paragraphs. These stories' commitment to surface values opened them, predictably, to the charge of lacking depth -- like the magazine in which they appeared. Their ironic, witty way of taking things made them inimical, or at least unresponsive to -- so the charge ran -- Life, which was disorderly, unmanageable, a matter not adequately dealt with ironically or stylishly. It is interesting that Nabokov, who published stories and the chapters of Pnin in the New Yorker , when asked whether his characters ever broke free from his authorial control, replied straight-facedly that no, he kept them severely under his thumb at all times -- they were "galley slaves." But Nabokov, being an expatriate and the author of Lolita , was immune to the criticisms his younger American New Yorker contributors received.

Two years after The Same Door was published Updike reviewed in the magazine Salinger's Franny and Zooey , and before he turned to some fairly sharp criticisms of "the extravagant self-consciousness" of Salinger's later prose -- especially in the overextended "Zooey" -- he addressed himself to the writer's earlier work. It had come upon Updike as "something of a revelation," particularly Salinger's conviction that "our inner lives greatly matter." Updike saw this conviction as consonant with the temper of current America in an age of "introversion," "of nuance, of ambiguous gestures and psychological jockeying on a national and private scale." Salinger's "intense attention to gesture and intonation," Updike wrote, made him "a uniquely pertinent literary artist." This is strong praise indeed, but not at all carelessly eulogistic; since the force with which Salinger struck young readers in the 1950s, especially those who themselves aspired to "write," can't be overstated. (It is a commonplace that those of us who began our teaching careers back then could assume that the one book every college freshman had read, probably more than once, was The Catcher in the Rye .)

Updike doesn't go on to point out that Salinger's penchant for "introversion" expressed itself in his fiction mainly in terms of anguish, nervous collapse, and suicide. Holden Caulfield speaks to us from the sanatorium where he's recuperating; the opening and closing pieces in Nine Stories , "A Perfect Day for Bananafish" and "Teddy," end with the protagonist's taking his own life. In between there is drunken anguish ("Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut"), a broken romance ("The Laughing Man"), and shell-shocked disorder ("For Esmé -- with Love and Squalor"). If this writer's mood and themes were coincident with national ones, then America was in for difficult times, which proved to be the case as the 1960s unrolled. By contrast, nothing really serious goes wrong in any of the stories in The Same Door: some sort of nonviolent resolution always occurs, and there is almost no attempt on Updike's part to explore a consciousness with complicated, penetrating analysis. Not that Salinger goes very deep either; his introversion, his preoccupation with extreme states of nerve are more given and asserted than they are explored.

What Salinger and Updike most notably do share is, in the words quoted from Updike's review, "intense attention to gesture and intonation." The most impressive intonation in Salinger's art, and where his true originality may be said to lie, is in the immediate, direct, unaffected address to the reader with which the storyteller launches his tale -- as in "The Laughing Man":

In 1928, when I was nine, I belonged, with maximum esprit de corps , to an organization known as the Comanche Club. Every schoolday afternoon at three o'clock, twenty-five of us Comanches were picked up by our Chief outside the boys' exit of P.S. 165, on 109th Street near Amsterdam Avenue. We then pushed and punched our way into the Chief's reconverted commercial bus, and he drove us (according to his financial arrangement with our parents) over to Central Park. The rest of the afternoon, weather permitting, we played football or soccer or baseball, depending (very loosely) on the season. Rainy afternoons, the Chief invariably took us either to the Museum of Natural History or to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This first-person mode is untypical of Salinger's collection as it is of Updike's, but the detail, the parenthetical ease of "(very loosely)," the generally humorous perspective on things -- all embodied in a confident, easy address to a reader from whom sophistication and irony are expected -- make the "intonation" a classic American one. It is an intonation shared by at least one other writer of the period, John Cheever, all of the stories in whose first collection were also published in the New Yorker . Here is the beginning of its opening one, "Goodbye, My Brother":

We are a family that has always been very close in spirit. Our father was drowned in a sailing accident when we were young, and our mother has always stressed the fact that our familial relationships have a kind of permanence that we will never meet with again. I don't think about the family much, but when I remember its members and the coast where they lived and the sea salt that I think is in our blood, I am happy to recall that I am a Pommeroy....

Here the narrator says something like, "Let me, without even clearing my throat, introduce myself to you in the most unassumingly direct way -- then we can get on with the tale." The "plots" of Cheever's stories seem much less important, even trivial and random, compared with the steady reassurance provided by the narrative speaking voice, available to all readers who use their ears.

The young Updike had of course read these stories by Salinger and Cheever published in his favorite magazine, whose ranks he had just entered as a salaried contributor. What in their work would he choose to steer clear of? Put another way, what resources had they drawn upon that he lacked, and therefore must supply with different ones? Their first resource, surely, was eastern urban-suburban life. Salinger grew up in New York City, knew his Fifth Avenue and Central Park; Cheever lived there for some years before moving to Ossining (Connecticut in the fiction) and taking over exurbia. By contrast Updike was, as he would later call one of his fictional stand-ins (in the story "Flight"), "a homely, comically ambitious hillbilly," a country boy whose family's move to the farm in Plowville, Pennsylvania, in 1945 made him feel more like a "hick" than his classmates from Shillington. But this was also his major resource: he had, as he put it later, "a Pennsylvania thing to say" and in the mid-1950s he was saying it in the autobiographical novel (Home) while working other material into New Yorker stories. A good strategy, except that, as noted earlier, when he moved to Ipswich in 1957, he decided to scrap the novel, going to work instead on The Poorhouse Fair -- another "Pennsylvania thing" but not an autobiographical one.

"Pennsylvania" thus enters only glancingly into the stories collected in The Same Door . It is there in the earliest one, "Friends from Philadelphia," where the boy, John Nordholm, is asked by his mother to procure a bottle of wine to serve some Philadelphia people who are coming for dinner. John enlists the help of Mr. Lutz, the breezy father of one of his friends, who purchases a bottle for John, ostensibly with the two dollars the boy has given him. At the story's end John glances at the label, Château Mouton-Rothschild 1937, unaware that he has been benignly tricked by Mr. Lutz. It is the purest O. Henry ending of any story in Updike's oeuvre, and for that reason looks like a youthful experiment in a mode that was not to prevail. Other loosely based Pennsylvania tales include "Ace in the Hole," about an ex-basketball star, a trying out of the character who would become Rabbit Angstrom and the first story in which the town is called Olinger; "The Kid's Whistling," set in a department store in what sounds like Reading; and a couple of school tales, one about a high-school teacher, another about a new girl in elementary school. It's not until the final and by far the best story in the book, "The Happiest I've Been," that the Olinger scene gets a fuller treatment and where we hear an intonation in the narrative voice predictive of Updike's best writing. Otherwise, except for "Dentistry and Doubt," where the protagonist visits an Oxford dentist, the scene of the stories is New York City. For the most part Updike's New York is sketched in pretty lightly, the focus being on a recently married man and his wife, sometimes with a baby daughter. They live on the upper West Side, later in a small apartment in the Village. There are a couple of Salingeresque efforts with clever titles ("Who Made Yellow Roses Yellow?" and "A Trillion Feet of Gas"), while "A Gift from the City," the collection's longest story, is a nod to the Cheever mode. (A young couple becomes involved in increasingly complicated relations with a black man to whom they've given money and who keeps returning for more.) From this group of urban tales I single out the two that seem most original, that could not have been written by Salinger, Cheever, or any writer except Updike: "Toward Evening," and "Snowing in Greenwich Village."

The first of these feels like a slight thing indeed, a "sketch" only eight pages in length but also distinctive insofar as it's difficult to name its subject precisely. A young man, Rafe, headed home from work in midtown and carrying a just-purchased mobile his wife has suggested he buy for their daughter, boards an uptown bus in front of St. Patrick's Cathedral, then proceeds past Columbus Circle and up Broadway until he alights at Eighty-Fifth Street, where he lives. The ride consists of Rafe first assisting a fat woman in black to board the bus, then gazing at two women who rouse him to erotic thoughts. He first regards a beautiful, stylishly dressed white woman who looks as if she speaks French and -- since she sports a copy of Proust's A l'ombre des jeunes rilles en fleurs -- probably does. Then, standing, he eyes a desirable, inaccessible "Negress" seated beneath him, and his steady look at her turns from a lustful fantasy to consideration of "the actual Negress" -- "the prim, secretarial carriage of her head, the orange skin, the sarcastic Caucasian set of her lips." When he alights from the bus she has "dwindled to the thought that he had never seen gloves like that before." In between his gazings at the two women, Rafe's eye is caught by an advertisement on the bus for Jomar Instant Coffee, ingeniously constructed so as to afford two versions of a man enjoying his coffee. But Rafe is too close to the ad for its ideal desired effect to work, and instead he begins to feel bus-sick.

Upon reaching home, he plays with his daughter, producing the mobile he has carried home. It is not a success: his wife had expected something more Calder-like and his daughter is simply not interested. After his "favorite" dinner of peas, hamburger, and baked potato, Rafe smokes a cigarette and looks across the Hudson to the Palisades where he notes that the Spry sign has gone on. The sign -- an actual phenomenon of the 1950s -- is described in close detail, and an imaginary account of it is conjured up by Rafe to explain how such an object came into being. (Among the amusing details of the account is a directive from the head office to turn it slightly south, since "Nobody at Columbia cooks.") After the fantasy about the Spry sign's genesis is completed, this paragraph concludes the story:

Above its winking, the small cities had disappeared. The black of the river was as wide as that of the sky. Reflections sunk in it existed dimly, minutely wrinkled, below the surface. The Spry sign occupied the night with no company beyond the also uncreated but illegible stars.

This is the first moment in the collection when, having finished the story, a reader might well ask, what of it? What is this story "about" -- indeed, is story the right name for it? After all, nothing happens, characters aren't "developed," there is no conversation between the husband and wife (Updike excised, from the version published in the New Yorker , what little there was), and the wife doesn't even speak. Events over the course of eight pages are linked only in the most tenuous way as moments in the mind of an inventive, rather playful consciousness. Yet the final paragraph sounds a deeper note, feels elevated and somber, out there on the edge of something with that black river, those sunken reflections on what one might call the loneliness of the Spry sign as imagined by a watcher, himself alone. For want of a better term, it may be called a poetic moment in which the language's density is out of proportion to anything it is "saying," and where the sequence in that final four-sentence paragraph is more heard than seen, aurally resonant even while visually precise. It is quite distinct, in its way of concluding, from the kind of thing either Salinger or Cheever provides, and a New Yorker reader who encountered it in the issue of February 11, 1956, might well have taken such note.

The story that follows "Toward Evening" in The Same Door , "Snowing in Greenwich Village," is probably the best known of Updike's New York City efforts, also of interest since it inaugurates what he would later call the Maples stories, about the fortunes of a married, then divorcing, couple and their children. It's also Updike's first story to savor of the illicit -- sexual temptation and the married man's close escape (or is it his failure?). The word close is rather flagrantly highlighted at the beginning and end of the story: Richard and Joan Maple have just moved from the West Eighties to West Thirteenth Street and decide to invite for drinks a friend living in the neighborhood, Rebecca Cune, "because now they were so close." The third-person narrative is centered on Richard; his wife has a cold; the three of them talk and drink sherry and eat cashews; at one point they rush to look out the window as six mounted police gallop down the street. It is now snowing and for Joan at least, we are told, the snow comes as a sort of benediction on their marriage. When Rebecca, who has entertained them with a number of amusing, slightly odd stories, gets up to leave, Joan insists that Richard accompany her, "close" as she lives to them.

Earlier in the story Richard had helped Rebecca off with her coat, thinking to himself how "weightless" the coat had seemed, how gracefully he had managed this act. Generally he has been pleased with himself as host, presiding at this minor entertainment with a satisfaction not untouched by vanity. But when Rebecca invites him to come up and see her apartment, "in a voice that Richard imagined to be slightly louder than her ordinary one," he becomes nervous. Opening the door to her room, Rebecca announces that "It's hot as hell in here" but doesn't remove her coat; nor does Richard offer to help remove it, noting instead the prominent presence of a double bed. They look out the window, make further small talk, then Richard moves toward the door, deciding she has been standing "unnecessarily close" to him. Leaving, he makes a weak joke, delivered with a slight stammer, and she -- seeing he has attempted a joke -- laughs before he's finished it:

As he went down the stairs she rested both hands on the banister and looked down toward the next landing. "Good night," she said.

"Night." He looked up; she had gone into her room. Oh but they were close.

The story is artful and satisfying for the way it tempts a reader into interpretive moves while refusing to endorse any of them. When, in reviewing Salinger, Updike declared the current temper in America to be one of "nuance," of ambiguous gestures and psychological "jockeying," he used terms that fit the temper of "Snowing in Greenwich Village." Is Rebecca out to seduce Richard or just to tease him? Or is she innocent, and does she keep her coat on so as to respect his status as a married man? Or is she inviting him to help her take it off, then see what happens? Is Richard correct in deciding her moves are provocative, or is he deluding himself, as a somewhat vain, self-important, and insecure young married man might do? With retrospective knowledge of the Maples stories to come, are we justified in seeing this small instance of temptation as the entering wedge? If this is a story about fidelity and temptation, of suspicion directed at both the hero and The Woman, of desire and anger at desire, of self-satisfaction at having resisted the temptation for now -- how much of these mixed feelings does Richard Maple's author share with him? Does Updike know something Richard doesn't know? To answer these questions unambiguously is to prevail over the story by ignoring other, contrary possibilities. What the tempted but undeluded reader responds to instead is, I think, something more like nuance, as felt in the ring of that "Oh" in the final sentence --"Oh but they were close." Whatever happens in "Snowing in Greenwich Village," no one including the narrator is about to say exactly, to name it any more closely than does the final sentence. We're closer to the atmosphere of Chekhov than of O. Henry, or for that matter of either Salinger or Cheever.

But it is in "The Happiest I've Been," concluding and best story in The Same Door , that Updike first taps the rich vein of nostalgic, guilty affection that animates the "Pennsylvania thing" he had it in him to say. It is also the only story in the book told in the first person singular. Its style is distinct from both the impressionistic montage of "Toward Evening" or the tight, economical, rather taciturn presentation of "Snowing in Greenwich Village." It rejects the virtues of ambiguous gestures and psychological jockeying in favor of a more open, "sincere," even good-hearted vision of things. While it is still full of nuance, of delicate noticings and expressively voiced reflections, such noticings and reflections are put in the service of a perspective on life that is appreciative, wondering, accepting. At one moment the narrator, John Nordholm (back from "Friends from Philadelphia"), confides to us that he had "nearly always felt at least fairly happy." Whether his creator ever said something like that about himself, there is surely a temperamental affinity between the nineteen-year-old Nordholm, a sophomore at college, and the about-to-be twenty-seven-year-old Updike, who published this story, set in late December 1951, in the January 3, 1959, issue of the New Yorker . Wordsworth's declaration that "The Child is Father of the Man" seems relevant to mark the continuity between someone about to leave his teens and a somewhat older writer concerned to celebrate the adolescent becoming man, which is the burden of "The Happiest I've Been."

The correspondence between the particulars of John Nordholm's life, as laid out in the opening paragraphs of the story, with those of his creator's suggests that Updike was anxious not to hide behind the anonymous resources of fiction. Like his hero, Updike was nineteen in late December 1951, was in his sophomore year at Harvard, had met the "girl" (Mary Pennington) he fell in love with "in a fine arts course" (she was a student at Radcliffe). In the story John Nordholm is going to visit this young woman at her parents' home in Chicago, where Mary Pennington's father was a Unitarian minister. John Nordholm lives, as did Updike, with his mother, father, and maternal grandparents on a farm some four miles from Olinger (Shillington), bordering on the city of Alton (Reading), Pennsylvania. (The distance between the farm and Olinger/Shillington later becomes ten miles.) As John and his friend Neil Hovey, in whose car he is going to Chicago, leave the farm -- not directly for Chicago but first to a party with old Olinger high-school pals -- the hero takes a picture of the homeplace he won't see again until spring:

I embraced my mother and over her shoulder with the camera of my head tried to take a snapshot I could keep of the house, the woods behind it and the sunset behind them, the bench beneath the walnut tree where my grandfather cut apples into skinless bits and fed them to himself, and the ruts in the soft lawn the bakery truck had made that morning.

One says, seeing those bits of apple and those ruts in the lawn, that no one is making this up: its authority comes from an "I" who was also "really" there -- who had the experience.

Updike's self-confidence in openly trusting himself to speak truly in fiction about his younger self may be a matter of having picked exactly the right moment to bring that younger self back to life. He once declared his conviction that the first great wave of nostalgia hits us when we're done with high school and moved away from our hometown, launched on some sort of independent life, yet close enough to what life was once (and not so long ago) that we can be both involved with and detached from the experience. There is a moment during the party John and Neal attend when John, "sitting alone and ignored in a great armchair," watches his ex-classmates dance to records, still 78s ("Every three minutes with a click and a crash another dropped and the mood abruptly changed"). He notes the "female shoes" scattered about the room, and is suddenly moved to feel "a warm keen dishevelment, as if there were real tears in my eyes." The tears have to do, he thinks, with how things are superficially unaltered, how it's the same party he's been going to throughout his life, and how people have changed very little -- "a haircut, an engagement ring, a franker plumpness." Yet, the implication is, everything has changed, is different, unforeseen, potentially "tragic" -- a word the narrator uses about John's perception.

Among the quite ordinary events that follow, Neil Hovey proceeds to get drunk, sitting in the den and listening over and over again to Gene Krupa's "Dark Eyes" on the phonograph, while an unidentified girl keeps him company, silently reading issues of Holiday and Esquire . The girl has been brought by Margaret Lento, another acquaintance of John's, also drunk and now furiously dancing by herself, having been ditched by the host, who has taken off with another girl. Neil has promised to drive Margaret and the other girl home (they live on the far side of Alton, away from Olinger) and while John waits for him to pull things together, he amuses himself by reading in volume 2 of Thackeray's Henry Esmond , which he's removed from a glass bookcase. Finally Neil appears, addresses him affectionately as "Norseman," and says, "Let's go to Chicago." But first they must deliver the girls home, and the evening -- now middle of the night -- prolongs itself when Margaret invites them in for instant coffee. Neil and Margaret's friend retire to the couch for some necking, while Margaret and John, discussing her ex-boyfriend's character, have a satisfyingly intimate conversation -- "the quick agreements, the slow nods, the weave of different memories; it was like one of those Panama baskets shaped underwater around a worthless stone." She draws his arm around her shoulder and eventually falls asleep, wakened only by the milkman making his morning rounds. The boys leave, drop the other girl off, and in a short concluding section to the story head out, at 6 AM, for Chicago.

That concluding section, one of the best pieces of writing to be found anywhere in Updike, shows him exploiting, for the first time, the full resources of a remarkable voice. In "The Happiest I've Been" that voice builds in interest as the boys drive back through the dead stillness of Alton and Olinger, then pass close enough to John's house so that he imagines shooting out a pane of his parents' bedroom window with a .22. He thinks of his grandfather stamping around, waiting for his grandmother to make breakfast; then the turnpike entrance looms and he is "safe in a landscape where no one cared." At which point Neil asks him to take the wheel -- even though previously he had never trusted John with his father's car -- and promptly falls asleep. The landscape where no one cares unrolls itself:

We crossed the Susquehanna on a long smooth bridge below Harrisburg, then began climbing toward the Alleghenies. In the mountains there was snow, a dry dusting like sand, that waved back and forth on the road surface. Further along there had been a fresh fall that night, about two inches, and the plows had not yet cleared all the lanes. I was passing a Sunoco truck on a high curve when without warning the scraped section gave out and I realized I might skid into the fence if not over the edge. The radio was singing "Carpets of clover, I'll lay right at your feet," and the speedometer said 81.

But nothing momentous happens, except in Updike's sentences, as Neil sleeps on, even providing an accompaniment of homely snoring.

The promise of those words from the song "For You," the magical, providential sense that nothing bad will occur to them -- that the landscape where no one cares isn't, on the other hand, malign, and that the future really does lie ahead -- these and other feelings coalesce in a wonderful moment as they navigate the tunnel country and begin the descent to Pittsburgh. Neil wakes up, scratches a match to light his cigarette; at which point John experiences an extraordinary happiness that he accounts for in the story's concluding sentences:

We were on our way. I had seen a dawn. This far, Neil could appreciate, I had brought us safely. Ahead, a girl waited who, if I asked, would marry me, but first there was a vast trip: many hours and towns interceded between me and that encounter. There was the quality of the 10 A.M. sunlight as it existed in the air ahead of the windshield, filtered by the thin overcast, blessing irresponsibility -- you felt you could slice forever through such a cool pure element -- and springing, by implying how high these hills had become, a wide-spreading pride: Pennsylvania, your state -- as if you had made your life. And there was knowing that twice since midnight a person had trusted me enough to fall asleep beside me.

It's those final two sentences that makes the story's ending so powerful, convincing us that, indeed, this is the happiest John Nordholm has been and that he's more than right to feel that way. The penultimate sentence is long, complex, almost going overboard as it twice punctuates itself with dashes, suspending us over the course of the first one until we see that the participles ("blessing," "springing") are in apposition. There follows the lovely appreciation of "Pennsylvania, your state" followed by the recognition of such appropriation as extravagant, though forgivably so -- "as if you had made your life." Then, ushered in by the innocuous "And," comes the final revelation, directly stated, about the human circumstances that have made such happiness fitting, almost inevitable.

Updike knew what he had done here, at least so it seems when in 1985 he said about the story that "I had a sensation of breaking through, as if through a thin sheet of restraining glass, to material, to truth, previously locked up." Amusing and agile as the light verse is on occasion, technically impressive and resourceful as is The Poorhouse Fair , this final story in The Same Door , especially its conclusion, is the happiest Updike had yet been as a writer.

Copyright © 2000 William H. Pritchard. All rights reserved.