Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

| Foreword | p. ix |

| Prologue: "We Might as Well Win" | p. 1 |

| What I Learned from Winning | |

| Follow Your Heart-But Bring Along Your Head | p. 13 |

| It Starts with Belief | p. 26 |

| Leave Some Dents | p. 37 |

| Do Whatever It Takes to Communicate | p. 48 |

| To Earn Confidence, Confide | p. 54 |

| Bluff When You're Weak-And When You're Strong | p. 64 |

| Lose a Little to Win a Lot | p. 78 |

| Recruit Too Much Talent | p. 84 |

| Trust People-Not Products | p. 95 |

| What I Learned from Losing | |

| "Lucky to Stare So Boldly at Loss" | p. 109 |

| When Failure Is Inevitable, Limit the Damage | p. 118 |

| Find a Victory in Every Loss | p. 127 |

| If You're Breathing, You Still Have a Chance to Win | p. 136 |

| Build the Foundation of Victory During Defeat | p. 147 |

| Putting It All Together | |

| "It Was My Dream" | p. 161 |

| Everything but Winning Is a Distraction | p. 178 |

| Winning Leads to Winning | p. 197 |

| Johan Bruyneel's Cycling Career | p. 207 |

| Acknowledgments | p. 215 |

| Index | p. 217 |

| Table of Contents provided by Ingram. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

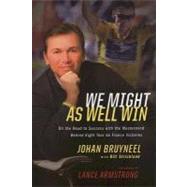

Excerpted from We Might As Well Win: On the Road to Victory with the World's Winningest Team Director and Mastermind Behind Lance Armstrong's 7 Tour de France Wins by Johan Bruyneel, Bill Strickland

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.