The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

THE EVOLUTION OF A MARXIST HOLY-ROLLER

TO THIS DAY, MY MOTHER SWEARS MY father tricked her into marrying him. Laurette Mathieu was a medical student in Liège, Belgium, during the waning days of World War II when she first met Sgt. James B. Henley of the U.S. Army. He was riding up and down the streets of Liège on his army-issue motorcycle, looking confused and lost. The local newspaper had run story the day before asking the citizens of Liège to please assist the Americans in any way possible and Laurette saw this as opportunity to help an American in trouble.

With the encouragement of her best friend, she yelled out, "Do you need directions?" Sergeant Henley took one look at the attractive young woman calling to him and immediately pulled over to the curb.

My mother recalls that she repeatedly explained the directions while my father feigned confusion, after which he said, "Just come with me and show me." She was reluctant, but like most Belgians, she was grateful to the American forces and wanted to help them in any way she could. So she hopped on the back of the motorcycle and pointed him in the direction of the base.

Once he'd gotten her on the motorcycle, Sergeant Henley had no intention of simply driving this pretty young Belgian woman to the base. He insisted on taking her home-which not only made him look chivalrous, but gave him the benefit of finding out where she lived. From that point on, he became a regular visitor in the Mathieu house, much to the delight of my grandmother, who worshiped the Americans. She was certainly not opposed to having her daughter entertain a Yankee, especially one as handsome and charming as Sergeant Henley.

For the next few weeks, Sergeant Henley came to see Laurette nearly every day, sometimes going AWOL from the base to do it. He told her all about his hometown of Camden, Arkansas, painting it as a perfect little town in the most picturesque part of the country. He also regaled her with stories about the beauty and glamour of America, most of which he'd stolen from the movies: before joining the army, he'd never been outside of small-town Arkansas.

Although she will admit to having been intrigued by my father's stories, my mother insists that she had no intention of marrying anyone. She was dating a fellow Belgian medical student at the time and had decided to wait until the war ended before deciding where her future might lie. But my father had already decided his future would include her.

"Laurette," he told her, "I've been told that I am being shipped out to the front any day now." His voice breaking, he told her how he'd gladly fight and give up his own life if it meant she could have a brighter future. In return, he just wanted one thing: the privilege of being her husband for a brief, shining moment.

Moved by his courage, Laurette was plunged into uncertainty. She told her two suitors that she needed time to think and made them both promise to leave her alone for a week while she tried to sort it all out. Her Belgian boyfriend honored her request and left her alone. My father also agreed to honor her wishes-and then proceeded to show up at her house for seven days in a row. On the eighth day he showed up at the house to find the Belgian boyfriend sitting in the dining room having dinner with the family. My father stormed out of the house and headed back to the army barracks.

To everyone's surprise-including my mother's-she jumped up from the dinner table and went straight to the base to find him. Until that moment, she hadn't realized the depths of her feelings for him-and now he'd stormed out, perhaps for good. When she caught up with him, my father did not mince words. "I'm about to be transferred to the front," he told her. "I don't have time to waste." She could either marry him, he said, or he would probably never see her again.

Unsure of what to do, but knowing that she didn't want to lose him forever, she agreed to marry him. A few weeks later, after she'd already become Mrs. James B. Henley, she learned the truth-the mission my father was being sent on was actually a routine exercise with a degree of danger only slightly greater than an army barracks inspection. By the time she discovered the truth, however, she was safely ensconced in the local army housing for young married couples and scared out of her mind.

Sergeant Henley has a different version of the story. To hear him tell it, my mother was immediately taken with the debonair American serviceman who bore a striking resemblance to Robert Mitchum. She fell hard for him and was just waiting to come to the promised land, America. If given the opportunity, she would gladly serve as his dutiful wife and bear him many children, all the while never removing her transfixed, adoring gaze. The way he tells it, she would beg him to tell her stories of life in America and could not wait to get married.

As I grew older and began to realize that my father's stories were often more fiction than fact, I began to suspect that my mother's version was the more accurate one. However, one thing still confused me: how could a woman, especially a strong-willed, intelligent one like my mother, be pressured into marrying before she was ready. I remember promising myself that when my time came, I would hold out for true love on my own terms. God would later punish me for this bit of hubris.

My parents were married on October 11, 1945, and suddenly my mother found herself thrust into the role of American military wife. Over the next fourteen years, she packed up and moved with him every couple of years-from Brussels to Munich to Heidelberg, Germany (where I was born in 1955), to Fort Riley, Kansas. Then, in 1959, my father retired from the army and took his Belgian bride and growing brood back to the small town where he had grown up.

Camden, Arkansas, was a far cry from the place my father had described when courting my mother. It was and still is like many southern Arkansas towns: quiet, friendly, devout, and mostly conservative, but with an underlying live-and-let-live attitude. When we moved there for good in the late fifties, the chief industry was timber and, thanks to the paper mills, you could smell Camden long before you could see it.

My father had had many years of distinguished army service in both Europe and Korea, but he never did advance past the rank of sergeant for one simple reason: he could not follow orders. Every time his career seemed to be on the rise, he would violate a curfew or go AWOL and soon find himself busted down a pay grade or two. Now that he was retired, his attempts at breaking into the private sector were not much better. Unable to follow directions from his bosses, he found himself wandering from job to job until he finally decided that his future would lie in that last-chance domain of the headstrong: he decided to become an entrepreneur. In the early sixties, he bought a gas station near downtown Camden and promptly became a part of the burgeoning American middle class.

My mother was keeping busy as well. My father might have had trouble sticking to one job, but there was another area in which he proved to have remarkable consistency: over the course of twenty years, my parents produced seven children-four boys and three girls. The three oldest, Danielle, Jim, and Bill, were all at least seven years older than the three younger children, Paula, David, and John. I was right in the middle, and my relationship with each of the two groups was very different. With the older set I was the kid sister, always trying to measure up. I never could quite succeed, as Danielle was a beauty queen, Jim was the brain, and Bill was the most popular teenager in town.

But my relationship with the younger kids was a different story. While Paula, David, and John were still very young, my mother took a job as a nurse to help provide for our family of nine. When that happened, I found myself responsible for getting the younger kids out of bed, making their breakfasts, and getting them dressed for school. Each night, I looked over their homework and made sure they brushed their teeth before bed. I seemed to fall naturally into the role of surrogate grown-up-and I took it very seriously.

I became aware early on that I was not like other kids. Instead of playing outside or watching television, I found comfort in reading about the world beyond Camden and imagining lives different from my own. In the third grade, we had a class project where all the kids were supposed to dress up as their favorite historical figures. Kids came to school that day dressed as Davy Crockett, Abraham Lincoln, and even Dorothy from the Wizard of Oz. I, on the other hand, asked my mom for a white lab coat so I could go dressed as Marie Curie. It was the first time I began to get the weird looks that would be the hallmark of my youth.

The rest of my brothers and sisters were relatively normal, which made my quirks stand out even more. My younger sister Paula, with whom I shared a bedroom and whose biggest concern was showing off her blond hair to its full advantage, used to bemoan what an oddball I'd become. "Susan!" she'd shriek. "Why can't you just be normal?" I would just laugh because I knew she was right. The evidence was everywhere, like the time in the fourth grade when I went to donate my used books at the school book fair. As my fellow ten-year-olds piled their Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys books on the table, I dropped off The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich .

I was always a daydreamer, and reading fed my imagination. On summer days, instead of going to play ball or hang around with other kids, I used to take Paula, David, and John to the library. I loved the library so much that we'd walk the two miles there even if it was 100 degrees outside-but then, when we got there, we had to do battle with the librarian. She was a cranky woman, and she would never let me look around anywhere but the children's section.

As soon as she'd turn her back, I'd sneak over to the history and biography shelves and conduct a hurried search for books about World War II. The most fascinating tales I'd ever heard were my parents' stories of wartime Europe, so I was forever trying to get my hands on as many books about Hitler, concentration camps, and the Russian front as I could. Not surprisingly, this alarmed the librarian, who once even called my father to complain when she caught me sneaking out of the children's section. Instead of getting me in trouble, she succeeded only in confusing my father, who couldn't figure out what the fuss was about. With seven active kids, my parents tended to reserve their worrying for times when someone was in danger of losing a limb, not when they were trying to read history books.

In the fifth grade I managed to sneak a copy of Karl Marx's writings out of the library. To an idealistic eleven-year-old, the concept of sharing the wealth among all people sounded wonderful. Excited at this new idea, I brought it up with my teacher, Mrs. Booker. "Under communism," I informed her, "everybody would be equal. There'd be no rich people, and no poor people." A look of bug-eyed horror crossed her face. "I work hard for my money," she said. "I'm not going to give it away to anyone." I argued with Mrs. Booker for a few minutes, trying to convince her that she would probably end up with even more money under a communist system, but inexplicably she remained unswayed.

My conversation with Mrs. Booker created something of a ripple in the community. A few of the other kids went home and told their mothers about our discussion, and the frightful prospect of possibly losing one of its young people to the lure of communism was too much for Camden to take. Some of the mothers notified the church leaders, and the following weekend, the whole Sunday school was asked to pray for my soul.

This would be a common thread throughout my early life: reading would usually get me into trouble. Having never traveled anywhere-save for a seemingly endless two-week, flu-ridden station-wagon trip to Jacksonville, Florida-reading took me out of Camden and into the world. I had always been a daydreamer, and reading took me a step further. The more I read, the more I became convinced that I was somehow being deprived of seeing the magnificent and fascinating places in my books. I'd had very little contact with the world outside Camden, but my love of reading convinced me of one thing: I decided early on that the quality I wanted most in a man was that he be able to "speak like a book."

For some reason, despite seven shots at it, my parents failed to produce even one shy wallflower of a child. I used to fantasize that our family was an Arkansas version of the Kennedys, conveniently overlooking the fact that we had no money, political clout, or Ivy League educations. Though we were a big, loving family, we were hardly the Kennedys-in truth, we were more like the Brady Bunch on amphetamines. We spent our evenings crowded around the dinner table, with each of the seven children vying to be heard over the shouting and each willing to offer opinions without the slightest provocation.

But one voice always rose above the tumult-that of my father. During the last ten years of his army service he'd served as a drill sergeant, shaping up young recruits with a two-step program of yelling and yelling louder. At home, he saw no reason not to raise his children in the same manner. Strict discipline was required in everything we did, from waking up at 05:30 every morning to making up our beds with hospital corners. We were to come directly home after school and, if there was a need to go out, we were given a rigid, nonnegotiable deadline as to when we were to return. Being late meant a whipping, which was accompanied by the inevitable lecture in which my father insisted he had to whip us because he loved us so much. During these times, he introduced us to the unique army vocabulary-words that might seem inappropriate at a dinner party but later came in handy for me during discussions about Kenneth Starr.

For my sisters and me, dating was pretty much out of the question. Even if we did happen to get a date with a local boy, the thought of having him meet Sergeant Henley was enough to dampen any romantic desire. But when she was seventeen, my oldest sister, Danielle, began seeing Bobby Jo Dickinson, a James Dean wannabe complete with ducktail, tight white T-shirt, and a souped-up '57 Chevy.

Because my father forbade any of us from going out on weeknights, Bobby Jo would drive his Chevy up and down our street honking his horn, and call Danielle at all hours of the night-all of which drove my father crazy.

Continues...

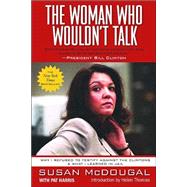

Excerpted from THE WOMAN WHO WOULDN'T TALK by SUSAN McDOUGAL with Pat Harris Copyright © 2003 by Susan McDougal and Pat Harris

Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.