Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

| Introduction | ix | ||||

|

|||||

| Foreword | xliii | ||||

|

|||||

| Clarification of Certain Names and Terms | li | ||||

| Preface | 1 | (4) | |||

|

5 | (4) | |||

|

9 | (4) | |||

|

13 | (9) | |||

|

22 | (6) | |||

|

28 | (10) | |||

|

38 | (13) | |||

|

51 | (7) | |||

|

58 | (11) | |||

|

69 | (7) | |||

|

76 | (9) | |||

|

85 | (6) | |||

|

91 | (10) | |||

|

101 | (10) | |||

|

111 | (10) | |||

|

121 | (14) | |||

|

135 | (8) | |||

|

143 | (12) | |||

|

155 | (24) | |||

|

179 | (16) | |||

|

195 | (10) | |||

|

205 | (14) | |||

| Epilogue | 219 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

FIRST ACT

In a story of this kind, it is difficult to locate the first act. For narrative convenience, I shall take this to be a trip I made in Africa which gave me the opportunity to rub shoulders with many leaders of the various Liberation Movements. Particularly instructive was my visit to Dar es Salaam, where a considerable number of Freedom Fighters had taken up residence. Most of them lived comfortably in hotels and had made a veritable profession out of their situation, sometimes lucrative and nearly always agreeable. This was the setting for the interviews, in which they generally asked for military training in Cuba and financial assistance. It was nearly everyone's leitmotif.

I also got to know the Congolese fighters. From our first meeting with them, we could clearly see the large number of tendencies and opinions that introduced some variety into this group of revolutionary leaders. I made contact with Kabila and his staff; he made an excellent impression on me. He said he had come from the interior of the country. It appears he had come only from Kigoma, a small Tanzanian town on Lake Tanganyika and one of the main scenes in this story, which served as a point of embarkation for the Congo and also as a pleasant place for the revolutionaries to take shelter when they tired of life's trials in the mountains across the strip of water.

Kabila's presentation was clear, specific and resolute; he gave some signs of his opposition to Gbenye and Kanza and his broad lack of agreement with Soumaliot. Kabila's argument was that there could be no talk of a Congolese government because Mulele, the initiator of the struggle, had not been consulted, and so the president could claim to be head of government only of North-East Congo. This also meant that Kabila's own zone in the South-East, which he led as vice-chairman of the Party, lay outside Gbenye's sphere of influence.

Kabila realized perfectly well that the main enemy was North American imperialism, and he declared his readiness to carry the fight against it through to the end. As I said, his statements and his note of confidence made a very good impression on me.

Another day, we spoke with Soumaliot. He is a different kind of man, much less developed politically and much older. He hardly had the basic instinet to keep quiet or to speak very little using vague phrases, so that he seemed to express great subtlety of thought but, however much he tried, he was unable to give the impression of a real popular leader. He explained what he has since made public: his involvement as defence minister in the Gbenye government, how Gbenye's action took them by surprise, and so on. He also clearly stated his opposition to Gbenye and, above all, Kanza. I did not personally meet these last two, except for a quick handshake with Kanza when we met at an airport.

We talked at length with Kabila about what our government considered a strategic flaw on the part of some African friends: namely, that, in the face of open aggression by the imperialist powers, they thought the right slogan must be: "The Congo problem is an African problem", and acted accordingly. Our view was that the Congo problem was a world problem, and Kabila agreed. On behalf of the government, I offered him some 30 instructors and whatever weapons we might have, and he was delighted to accept. He recommended that both should be delivered urgently, as did Soumaliot in another conversation--the latter pointing out that it would be a good idea if the instructors were blacks.

I decided to sound out the other Freedom Fighters, thinking that I could do this by having a friendly chat with them at separate meetings. But because of a mistake by the embassy staff, there was a "tumultuous" meeting attended by 50 or more people, representing Movements from ten or more countries, each divided into two or more tendencies. I gave them a speech of encouragement and analysed the requests they had nearly all made for financial assistance and personnel training. I explained the cost of training a man in Cuba, the investment of money and time that it required, and the uncertainty that it would result in useful fighters for the Movement.

I gave an account of our experience in the Sierra Maestra, where we obtained roughly one soldier for every five recruits, and a single good one for every five soldiers. I put the case as forcefully as I could to the exasperated Freedom Fighters that most of the money invested in training would not be well spent; that a soldier, especially a revolutionary soldier, cannot be formed in an academy but only in warfare. He may be able to get a diploma from some college or other, but his real graduation--as is the case with any professional--takes place in the practice of his profession, in the way he reacts to enemy fire, to suffering, defeat, relentless pursuit, unfavourable situations. You can never predict from what someone says, or from his previous history, how he will react when faced with all these ups and downs of struggle in the people's war. I therefore suggested that training should take place not in our faraway Cuba but in the nearby Congo, where the struggle was not against some puppet like Tshombe but against North American imperialism, which, in its neo-colonial form, was threatening the newly acquired independence of nearly every African people or helping to keep the colonies in subjection. I spoke to them of the fundamental importance which the Congo liberation struggle had in our eyes. Victory would be continental in its reach and its consequences, and so would defeat.

The reaction was worse than cool. Although most refrained from any kind of comment, some asked to speak and took me violently to task for the advice I had given. They argued that their respective peoples, who had been abused and degraded by imperialism, would protest if any casualties were suffered not as a result of oppression in their own land, but from a war to liberate another country. I tried to show them that we were talking not of a struggle within fixed frontiers, but of a war against the common enemy, present as much in Mozambique as in Malawi, Rhodesia or South Africa, the Congo or Angola. No one saw it like that.

The farewells were cool and polite, and we were left with the clear sense that Africa has a long way to go before it reaches real revolutionary maturity. But we had also had the joy of meeting people prepared to carry the struggle through to the end. From that moment, we set ourselves the task of selecting a group of black Cubans and sending them, naturally as volunteers, to reinforce the struggle in the Congo.

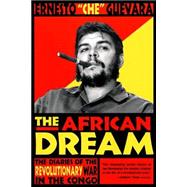

Excerpted from THE AFRICAN DREAM by Ernesto `Che' Guevara. Copyright © 1999 by Archivo Personal del Che.

Translation copyright © 2000 Patrick Camiller. Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.