What is included with this book?

| Map | p. viii |

| Fate in the Convergence | |

| Malta, Summer of 1942 | p. 3 |

| Fred and Minda | p. 8 |

| Fire Down Below | p. 15 |

| To Belfast and Oslo | p. 23 |

| Lonnie Dales | p. 28 |

| The Second Great Siege | |

| The Fortress | p. 37 |

| Gladiators | p. 40 |

| From Nelson to Cunningham | p. 46 |

| Debut of the Luftwaffe | p. 49 |

| Siege on the RAF | p. 55 |

| Allies | |

| Out of Norway | p. 65 |

| Operation Harpoon | p. 68 |

| Malta's Last Hope | p. 75 |

| SS Santa Elisa, June 23 | p. 81 |

| SS Ohio, June 23 | p. 89 |

| Operation Pedestal | |

| Master Dudley Mason | p. 99 |

| The Clyde | p. 105 |

| Cairo | p. 110 |

| Admiral Neville Syfret | p. 113 |

| Lieutenant Commander Roger Hill | p. 117 |

| Operation Berserk | p. 121 |

| Into the Mediterranean | |

| Operation Bellows | p. 127 |

| Dive of the Eagle | p. 132 |

| Dive-Bombers at Dusk | p. 139 |

| Bad Day for Secret Weapons | p. 146 |

| Ithuriel and Indomitable | p. 151 |

| Nigeria and Cairo | p. 157 |

| Captain Ferrini's Amazing Hat Trick | p. 164 |

| Hell in the Narrows | |

| This One's for Minda | p. 171 |

| Creams on the Water | p. 179 |

| Moscow | p. 183 |

| Retreat of the Commodore | p. 186 |

| Il Duce's Pajamas | p. 192 |

| Night of the E-Boats | p. 198 |

| Hell in the Aftermath | p. 205 |

| Survivors | |

| Santa Elisa | p. 211 |

| Waimarama | p. 221 |

| Swerving Toward Malta | p. 230 |

| Just a Mirage | p. 236 |

| Lame Duck off Linosa | p. 242 |

| Nowhere to Hide | p. 248 |

| Two Men, One Warrior | |

| Black Dog | p. 257 |

| The Bofors | p. 260 |

| Nerves of Steel | p. 265 |

| The Teetering Tirade | p. 270 |

| Nine Down, Four Home, One to Go | p. 274 |

| Grand Harbour | p. 276 |

| Moscow Saturday Night | p. 281 |

| The Cablegram | p. 284 |

| Malta Rises | p. 287 |

| Afterword | p. 291 |

| List of Ships | p. 295 |

| Source Notes and Acknowledgments | p. 299 |

| Bibliography | p. 315 |

| Index | p. 323 |

| Table of Contents provided by Ingram. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

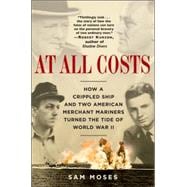

Excerpted from At All Costs: How a Crippled Ship and Two American Merchant Mariners Turned the Tide of World War II by Sam Moses

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.