What is included with this book?

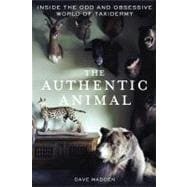

DAVE MADDEN is a professor at The University of Alabama. He lives in Tuscaloosa and co-edits The Cupboard, a quarterly pamphlet.

“Don't let the gory subject matter repel you from this charming account of the cast of kings, artists, biologists, circus performers, and ordinary folks who populate the world of taxidermy. Madden's investigation is marked by appealing candor, literary references, and atmospheric descriptions of (and fondness for) the subculture and its adherents…this book muses with verve and wit on the relationships between human and animal, art and artifact, as well as on the collector's obsession.”– Publishers Weekly

Madden…investigates the subculture of taxidermy…[and] can be a bit tongue in cheek…when he wonders “what would happen if the tables were turned?” and the animals put the humans on display… [A] sometimes chilling tour of an intriguing subculture. – Kirkus Reviews

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.