Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

| Foreword | p. ix |

| Preface | p. xi |

| Manners Acquired as a Child | p. 3 |

| Manners Learned While an Undergraduate | p. 21 |

| Manners Picked up in Graduate School | p. 38 |

| Manners Followed by the Phage Group | p. 55 |

| Manners Passed on to an Aspiring Young Scientist | p. 72 |

| Manners Needed for Important Science | p. 94 |

| Manners Practiced as an Untenured Professor | p. 118 |

| Manners Deployed for Academic Zing | p. 136 |

| Manners Noticed as a Dispensable White House Adviser | p. 155 |

| Manners Appropriate for a Nobel Prize | p. 173 |

| Manners Demanded by Academic Ineptitude | p. 195 |

| Manners Behind Readable Books | p. 213 |

| Manners Required for Academic Civility | p. 240 |

| Manners For Holding Down Two Jobs | p. 259 |

| Manners Maintained When Reluctantly Leaving Harvard | p. 286 |

| Epilogue | p. 316 |

| Cast of Characters | p. 329 |

| Remembered Lessons | p. 343 |

| Table of Contents provided by Ingram. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

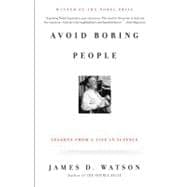

Excerpted from Avoid Boring People: Lessons from a Life in Science by James D. Watson

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.