Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

| Introduction: Why Learning? | ix | ||||

|

1 | (30) | |||

|

31 | (28) | |||

|

59 | (32) | |||

|

91 | (50) | |||

|

141 | (42) | |||

|

183 | (26) | |||

|

209 | (36) | |||

|

245 | (28) | |||

|

273 | (38) | |||

|

311 | (36) | |||

| Conclusion: Secrets of a Tiger's Success | 347 | (4) | |||

| Notes | 351 | (24) | |||

| Bibliography | 375 | (24) | |||

| Acknowledgments | 399 | (2) | |||

| Index | 401 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Studying killer whales off the Canadian Pacific coast, researcher Alexandra Morton spotted an eaglet learning that not all birds are alike. The nest he had hatched in was in a fir tree by the shore. Gazing keenly about, the eaglet saw a great blue heron standing on floating kelp. Deciding to do likewise, the eaglet flew down to alight on the kelp. Instead of standing on it with splayed toes as the heron did, he griped it like a bough. The seaweed sank when the young bird landed on it, and he plunged in. He struggled free, but didn't give up the project. "Again and again the eagle alighted and sank to his breast, flapping wildly to avoid drowning," writes Morton. It took all morning before the eaglet abandoned hope of becoming the Terror of the Kelp.

An experimental process of trial and error persuaded the young bald eagle that at least one perching place wasn't for him. Some baby animals are born with most of the skills they will use in their lives, and need to gather very little information to make their way through life. Others must learn many skills and collect a great deal of information if they are to survive.

There are many ways to learn. An orphaned fox cub at a rehabilitation center who stops panicking every time someone puts a food pan in its cage is becoming habituated. An owlet flapping its wings and trying to fly to a higher branch is practicing. Wrestling puppies come to understand social relationships by playing. A tiger cub with newly opened eyes is learning to see by forming neural connections. A dayold chick that begins foraging by pecking indiscriminately at seeds, bugs, and its own toes (and switches to pecking only at seeds and bugs) is using trial and error. When a young raven, cawing fiercely, joins with the rest of the flock in mobbing a creature it has never seen before, the fledgling is undergoing social conditioning. These are all forms of learning.

Researchers have carefully examined many of the ways animals learn, and have focused a lot of attention on which ways to learn are available to all kinds of animals and which are special to only a few top-flight species, particularly the human species. But that animals of every kind learn in at least some ways is undisputed.

Why learn?

A young rabbit being closely pursued by a predator zigzags crazily from side to side. The rabbit covers less ground this way, but because it's nimbler than a big wolf or bobcat or eagle, it stands a chance of getting away by dodging. This is an excellent strategy that might not occur to me if a monster were suddenly hot on my heels. The young rabbit doesn't have to learn zigzagging -- a rabbit's life is short, and if it had to learn its evasive tactics would be even shorter. This is great, unless the rabbit stupidly jumps out in front of your car, realizes that it's in trouble, and starts zigzagging down the road in front of the car. If rabbits lived a long time, and were protected from predators by their parents while they slowly learned about the world, we might hope they would come up with a better way not to be hit by cars. (How about not jumping in front of them in the first place, pal?) Not having time, rabbits are born ready to zigzag.

Being prepared ahead of time or thinking on your feet?

Why go to the trouble of learning if you can just be born knowing how to dodge? You may dodge when it's inappropriate, like the rabbit in front of the car. You may be unable to learn new strategies, like crossing the road after the car comes, not before. Species vary tremendously in how much of their behavioral repertoire is learned. The zoologist Ernst Mayr proposed the metaphor of closed and open programs. Mayr defines a closed program as one which does not allow appreciable modifications, and an open program as one "which allows for additional input during the lifespan of its owner."

An animal with a closed program recognizes mates without having to learn what their species looks like, usually by one or two key features or a ritualized display. An animal with an open program learns what prospective mates should look like, often by observing its own family. A frog doesn't need to learn what a suitable frog mate looks like, but an owl must learn to spot a suitable partner. Many animals have closed programs for some aspects of their behavior and open for other aspects.

I once raised two small Virginia opossums whose mother had been hit by a car, and they operated largely on closed programs. Things they simply knew included how to hiss (showing 50 teeth), how to curl up in a ball, how to hang by their tails, how to beat up a cat that jumped them, and how to catch fledgling birds. They knew that fledgling birds and rotten apples were good to eat (they thought almost everything was good to eat). They knew they should waddle along, sniffing, until they smelled food. They knew that climbing upward was a good way to be safe.

They were open to some new information. They learned that I was a friend who would protect them, and so when I took them to the woods, thinking they'd like to explore, they whirled in alarm and clambered up my legs-because they hadn't learned to know the woods. They learned that I wouldn't really let them fall if they refused to hang by their tails. They learned that my dog and my cat wouldn't bother them. And that was about all.

Species with short lifespans, like opossums, have little time to learn, so they are apt to have more closed than programs open ...

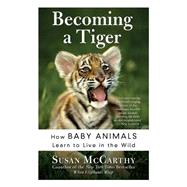

Becoming a Tiger

Excerpted from Becoming a Tiger: How Baby Animals Learn to Live in the Wild by Susan McCarthy

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.