Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

| Introduction: Gabriel's Helper | |

| Book 1 | |

| Introduction | |

| Beginnings | |

| Coming of Age | |

| Wedding | |

| Mourning | |

| Book 2 | |

| Introduction | |

| Rosh Hashanah | |

| Yom Kippur | |

| Sukkot and Simchat Torah | |

| Hanukkah | |

| Purim | |

| Passover | |

| Yom HaShoah and Yom Ha'atzmaut | |

| Shavuot | |

| Fast Days | |

| Sabbath | |

| Book 3 | |

| Introduction | |

| Prayer | |

| Kosher | |

| The Jewish Home | |

| Outside the Home | |

| Study | |

| Bibliography | |

| Index | |

| Table of Contents provided by Publisher. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Gabriel's Helper

There is a medieval Jewish legend, "Gabriel and the Infants," that goes like this: In the months before a Jewish child is born, it is visited in the womb by the Angel Gabriel. There, in the warmth and Silence of the mother's body, the angel teaches the baby all of Jewish learning -- the Torah, the rituals, the holidays, the deepest truths of Jewish wisdom. The baby absorbs it all, just as it takes nourishment from its mother. But suddenly, as the baby is about to be thrust into the world to eat and breathe on its own, the angel presents it with a similar intellectual challenge. Right before birth, Gabriel strikes the Child on the upper lip, and all the teachings are instantly forgotten.

I loved hearing this story as a child. For one thing, it explained that otherwise useless indentation above my upper lip. For another, it gave me a timeless relationship with all Jewish knowledge. The process of living a Jewish life seemed to have more to do with remembering what is inherently mine rather than learning anew. As I encountered Jewish rituals and holidays, Jewish ideas and philosophies, they seemed to have a familiar ring. Sometimes the image of Gabriel flashed before my eyes.

The legend of Gabriel also provided me with something else: company, I knew that as a Jew I was not alone, From my earliest beginnings, there was someone there -- teaching, coaxing, and guiding. This notion of a Gabriel in one's life is built into virtually all of the Jewish life cycle events. At the first initiation rite, thebrit,there is thesandek,the man who holds the baby during the cutting. A bar or bat mitzvah cannot take place without a teacher who passes on the ancient words and melodies to a new generation. At a wedding, the bride and groom are traditionally givenshomrim,or royal guards, who escort them to the wedding canopy, And even in death, Jewish law ensures that the body is not left alone from the time of death until the moment of burial. It is customary for family members or friends to take turns standing watch at the bier.

Judaism provides community. It does so in the major life cycle events as well as in the more mundane moments of the day, the week, the month, and the year. Daily, Sabbath and festival services ring out from synagogues across America and the world in a variety of styles and beliefs. Home rituals, from Sabbath candle lighting to Passover seder meals, connect the individual with the Jewish community at large and with practices both ancient and modern.

In American society, there is no coercion to be a religious person. Freedom of religion means that we are as free to dowithreligion as we are to do without. Those who convert to Judaism are nowadays called Jews by choice. But, as has often been said, every Jew today is, in fact, a Jew by choice. We can go to synagogue or not go to synagogue, pray or not pray, mark the life cycle events or ignore them. Judaism is out there, something external, something we can choose to partake of -- or dismiss.

But the legend of Gabriel and the Infants provides another model. Gabriel teaches us that Jewish knowledge is not external, removed from life, but something inside: the very stuff of life that must be reckoned with and rediscovered. And, just as important, Gabriel reminds us that built into Judaism are guides, companions, and teachers who can help both those born Jewish and others who want to learn about the faith. These lessons, I believe, are ones that American Jews desperately need. Judaism can help ease the modern sense of isolation and loneliness, providing a sense of belonging in the present and a sense of connection with the past.

A third lesson I take from Gabriel is that Jewish teaching is not monolithic. What is good for one person may not be the answer for others. Gabriel visits each of us with a personalized lesson. Of course, there is Sinai, with its dramatic revelation for all the faithful, but there is also the awareness that each Jew has to forge an individual relationship with the divine.

In this book, I will lead the reader through the process of Jewish discovery, moving first from birth rituals to funeral rites, and then through the Jewish months, from one Jewish New Year to the next. Along the way, I will take a look at how different Jews have found meaning, richness, and variety in the tradition and made it their own.

The book is divided into three sections, each representing a cycle of Jewish life. The first section will demonstrate how Judaism responds to the natural events of life, looking at the ceremonies associated with birth, the coming of age, marriage, and death.

The second section will deal with the major milestones of the Jewish calendar -- the classic holidays, such as Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, Hanukkah and Passover -- as well as the minor fast days and holidays created in the twentieth century to respond to the tragedy of the Holocaust and the Creation of the modern State of Israel.

The third and final section will explore the rhythm of the Jewish day, in which time is marked with prayers and blessings. This section will look at Jewish prayer, the laws ofkashrut,and Jewish ethical behavior in everything from charitable giving to family life.

BEING JEWISH IN AMERICA AND IN ISRAEL

This book grew out of a rethinking and reexamination of Jewish life during a sabbatical I took with my family in Jerusalem in 1997-1998. My previous sabbatical, taken over a decade earlier, was spent at Harvard Divinity School exploring the religions of the world. The literary product of that year, my bookThe Searcher God at Harvard,struggles with concepts of pluralism and belief. It deals with the question of how someone Orthodox, like myself, can embrace and appreciate the truths of other religions.The Searchgained widespread acclaim, with one reviewer calling me "a kind of Gulliver of faith," but there was criticism too, perhaps the most stinging from a rabbi in a right-wing Jerusalem yeshiva who "caught" one of his students reading my unorthodox hook. He was dismissive, telling the student: "Why does Goldman run off and study Christianity and Islam when he barely knows Judaism?" This new book is my effort to examine not the faiths of others but my own faith, to look deep into its practices and history and try to invigorate it with new meaning and purpose. I undertake this examination not as the yeshiva boy I once was but with the insight of a Gulliver who has seen the lives of others and can now reflect better on his own.

This book is not a right-wing or even Orthodox approach. While Orthodoxy is my home, I believe that Judaism can and should be celebrated in a variety of ways. I am that rare breed: an Orthodox pluralist, someone who believes that the right answer for me is not the answer for everyone. After all, if I embrace pluralism in my approach to other religions, I must embrace it as well within my own faith. In these pages, I will demonstrate a variety of Jewish practices: some traditional, some innovative, and -- many of the best of them -- a combination of the two.

In recent years, the pietistic ArtScroll Series of books has enjoyed enormous popularity in Orthodox circles. Riding a wave of Orthodox fundamentalism, ArtScroll has found a niche in a community obsessed with unbending adherence to halacha, Jewish law. Every aspect of life, from the bedroom to the synagogue to the kitchen stove, has found regulation in ArtScroll's three hundred volumes, often lost in this effort, however, has been much of the nuance, subtlety, poetry, and flexibility of traditional Judaism. To put it plainly, Judaism is much more fun than the ArtScroll Series would have you believe.

To me, the way in which people live their Judaism tells as much. about Judaism as what is legally required in the halachic system. I have tried to enrich this volume with stories -- stories from my own life and from the lives of other Jews who, while far from perfect, are striving to live a meaningful Jewish life.

This is not a comprehensive religious text on Jewish observance. Do not look at this book as a manual, but as a beginning. There are many places to turn -- even to ArtScroll -- for greater depth and knowledge. In these pages, I want to demonstrate how Judaism developed over the centuries and provide a snapshot of how it is observed at the turn of the new millennium.

During my year in Jerusalem, I studied with some of the greatest teachers of Judaism at the Shalom Hartman Institute and at the Jerusalem Fellows. I read in the finest libraries of Jewish law and literature at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and at the campus of Hebrew Union College in Jerusalem. I dipped into the cacophonous and exuberant study halls at the Mir Yeshiya, Aish Hatorah, and Chabad-Lubavitch. I availed myself of the riches of the stately Diaspora Museum on the campus of Tel Aviv University. But I probably gained the most from extended conversations with several pulpit rabbis from around the world -- people who, like me, were on sabbatical for the year in Jerusalem. They represented all the major modern movements in contemporary Jewry -- Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform -- and helped root my academic inquiry in the reality of contemporary. Jewish practice.

My study of Judaism was also set against the backdrop of a year of extraordinary political and security developments. I arrived with my wife, Shira, and our three children-on August 1, 1997, the day after two Arab suicide bombers killed fifteen people at the busy outdoor-market in Jeruslem known as Machane Yehudah. Less than a month later, Shira was a block away when three Arab terrorists killed themselves and four others on the pedestrian walkway of Ben Yehudah.

The year 1998 arrived with renewed fear of chemical attacks by Iraq's Saddam Hussein. The fears were rooted in the 1991 Persian Gulf War, when Saddam rained thirty-nine Scud missiles on Israel. With concerns about a renewed conflict, we were sent scurrying to find gas masks in adults' and children's Sizes. We sealed a room of our Jerusalem apartment in fear of an attack. At the last moment, the threat of war was averted after a settlement brokered by the United Nations Secretary General, Kofi Annan.

It wasn't until a year after we left Israel that a new prime minister, Ehud Barak, ushered in an era of new hopes (and fears) by reopening long-dormant negotiating channels with the Palestinians and Syrians.

While the issues of survival are always paramount in Israel, the issue of religion was never deep beneath the surface during our visit. Until I lived there, I never understood what power religion had in Israel, in both good ways and bad. I had read so much about the deep division over religion -- how the secularists hated the ultra-Orthodox, known as theharedim,and vice versa. I saw much evidence of this on the streets of Tel Aviv and Jerusalelm, But, living in Israel, I came also to see something else: how much the Orthodox and secular have incommon.Judaism is a central part of the identity of the non-Orthodox. For virtually all Israeli Jews, religion serves as a common denominator when it comes to life cycle events and holiday celebrations. Regardless of whether you are religious or secular, you don't work on Yom Kippur. That doesn't mean you go to synagogue -- many Israelis go to the beach (and some go to both). But for all it is a festival. Nearly all Israeli Jews (95 percent) circumcise their sons, and virtually all are married under achuppah,a Jewish wedding canopy. There are problems, to be sure. Israelis have no choice when it comes to religion. The only religious Judaism that is officially recognized in Israel is Orthodoxy. About 15 percent of Israeli Jews are orthodox, but the Orthodox grip on the religious establishment is absolute. There is no formal sanction (and little government support) for the non-Orthodox movements. During our year in Israel, Conservative and Reform Jewry struggled to gain some recognition but made little headway in the face of the powerful Orthodox political parties.

Clearly, the Israeli's life is governed by the religious calendar and shaped by Jewish life cycle events, There is no such guarantee for American Jews, many of whom have no relationship to the Jewish calendar on either a communal or a personal level. What came through clearly to me during our year in Israel is how different American Jewry is from Israeli Jewry. American Jews have many options when it comes to Judaism -- they can choose between the three major religious movements, the smallest of which is Orthodoxy. But on a day-to-day level, most American Jews have little relationship with or knowledge of the Jewish cycle of life.

Today, there are more Jews in America than there are in Israel (although demographers, say that within the next ten. years Israel's Jewish population will surpass America's). Of the 15 million Jews currently in the world, roughly 6 million live in the United States, and about 5 million live in Israel. There remain about 1.5 million in the former Soviet Union and more than 1 million in Western Europe, principally in France and Great Britain. In addition there are 300,000 in Canada, 233,000 in Argentina, 120,000 in South Africa and 130,000 in Brazil. The remaining 5 percent are scattered throughout the world.

WHAT DO ALL JEWS HAVE IN COMMON?

What connects this dispersed people? Some say a common history. We all share a story that includes both triumph and tragedy. While we all have our personal Gabriel, the tradition teaches that all jews Stood at Sinai thirty-five hundred years ago when God gave the Torah to the Jewish people. The souls of Jews for all time were there, the rabbis state, when the Jews answered God's charge with the wordsna'asheh v'nishma:"We will do and we will listen." By plating all Jews at Sinai, the rabbis argue that all are included in the covenant. History is a strong bond.

Others say that all Jews are connected by a common wisdom, as embodied in Jewish writings, both sacred and secular. We are guided by the Torah, the Talmud, and the codes of Jewish law developed over the centuries, as well as by the genius of Maimonides, the Baal Shem Tov, Herzl, Freud, and Einstein. Still others point to our ancestral home and the imperative to keep modern Israel a safe and thriving nation. When Israel is at risk, Jews everywhere feel endangered. All of these are powerful connections.

Last, Jewish ritual serves as a powerful connection between all Jews. It occupies a special place because it sanctifies all these elements -- our history, our ideas, and our land -- through acts that unite us in common practice.

Ritual acts aremitzvot,acts of obligation, more commonly known in the singular form,mitzvah.By the count of the rabbis of the Talmud, there are 613mitzvot.There are two kinds ofmitzvot,those that involve human relations and those that involve relation with the divine. Examples of the former include "Thou shalt not steal," and the imperative to "love the stranger? Examples of the latter -- between humankind and God -- include "keep the Sabbath" and the obligation to pray.

GOD AS FATHER? MOTHER? LOVER?

Each of the modern branches of Judaism sees God in a different way. And its God-view shapes the ritual. The Orthodox, it might be argued, see God as Father, demanding and exacting. God loves us, the Orthodox say, but it is a conditional love, dependent on our actions. For the Orthodox, ritual reigns supreme, especially the rituals between God and man. The Orthodox punctiliously watch what they eat (kosher only), what they wear (modest garb), and how often they pray (three times a day).

For the Reform, God is Mother, whose love is unconditional. The details of themitzvot,are not important; if she cares about ritual, it is only in a nostalgic way. The important thing is that we're good to our fellow human beings and try to leave the world a better place than we found it. Reform emphasizes themitzvotinvolving human relations, such as helping the poor, rather thanmitzvotinvolving obligations to God.

The Conservatives, however, see God as a lover. According to this approach, Jews are in a partnership with God in which God listens and we listen. God wants us to do God's will, but that will is not static. It changes as we change. The Conservatives believe that God's law is modified to fit the modern circumstance. Hence, ritual is an elastic phenomenon that changes with the times.

In this book I will deal for the most part Only with the three major branches, but let me just extend this analysis to one Other branch: the small Reconstructionist group. Reconstructionism sees God as neither Mother, Father, nor Lover. The Reconstructionists do not see God as a noun at all, but as a verb. God is the catalyst that enables us to actualize who we are as people and as a nation. We can use ritual to take us where we need to go. It is an instrument for our use.

My friend Elie Spitz, a West Coast rabbi who was on sabbatical with me in Jerusalem, likens the denominations to a deck of cards. My ritual summary above emphasizes the top card -- the ritual-bound Orthodox, the ritual-free Reform, the ever-changing Conservatives, and the utilitarian Reconstructionists. "All too often they play only their top card," Rabbi Spitz would say of the branches. In fact, the decks of all the denominations include the ritual card, just as all the denominations include love, change, and acts of charity, These days, ritual might be seen as the wild card. In all the denominations, including the Reform, the ritual card is moving higher and higher in the decks. In May 1999, the Reform movement -- which for more than a hundred years had stood squarely against ritual observane -- took the extraordinary step of encouraging its members to reconsider traditional observances, such as embracing the dietary laws and observing the Sabbath. The movements abbinical body, the Central Conference of American Rabbis, issued the challenge using the wordsmitzvahandmitzvot-- terms more often utilized by the Orthodox.Mitzvot,the Reform rabbis said, "demand renewed attention as the result of the unique context of our times." Among all branches of Judaism, there is a growing awareness that ritual acts that are specifically Jewish have the power to create and preserve the Jewish community.

Take lighting candies on Friday night to usher in the Sabbath, an act traditionally performed in the home by Jewish women. The four denominations might have a different explanation for the act, but they all would see it as having great merit. The Orthodox say that women must light the candles because on Sinai that is what God told Moses that Jews must do in perpetuity. It is a practice that goes back to our matriarch Sarah, who lit candles in Abraham's tent, the Orthodox explain. The Conservatives would say that yes, we are commanded to light, either by Sinai or by the tradition. But it is not only women who must light; men have the obligation too. Times change. The Reconstructionists might talk about how lighting chases away the darkness and ennobles our spirits. And the Reform would argue that lighting candles on Friday night is a matter of personal choice, but certainly it is a ritual of great beauty.

To my mind, the important thing is not why you light, just that you light. What is the value of ritual? There are many answers. On a fundamental level, a ritual act connects you with all the others who have done that ritual, both past and present. Light the Sabbath candles and think of all the candles being lit by members of your congregation that night. Then think about all the candles in your city, in your country, in the world. Then think of all the candles ever lit by Jewish women and men through the ages, back to the matriarch Sarah. Now that's a lot of light.

On another level, doing a ritual act connects the Jew to a power larger than ourselves. If we are to believe on some level that God -- whether Mother, Father, Lover, or Catalyst -- wants us to do this act, then lighting the candle or keeping the Sabbath or having abritor attending a seder or helping the poor connects us with the Divine. On a vertical level we are connected to God; on a horizontal level, to others who have done these acts, both past and present. What emerges for me is a web of light.

BEING JEWISH MEANS HAVING JEWISH CHILDREN

How do we pass Judaism on to our children? For the Israeli, it is easy. Judaism is there as part of the atmosphere -- in the language, in the food, and in the music as well as in the events of the year and one's life. For the American Jew, who lives in a place where Judaism is a minority culture, education is essential: we can teach our children our history and our wisdom and our love for the land. But nothing makes it more concrete than ritual.

I recently heard a Reform rabbi talk to a group of parents of teenagers about intermarriage. Alarmed by statistics showing that more than 50 percent of Jews are marrying out of the faith, the rabbi encouraged us not to send our kids off to college without "the talk." "Tell them that they can have friends from all over, but the person they marry should be Jewish," he said. I remarked that I've been working on it since my children were born. "How?" he asked. I explained that every night before I put my children to sleep, I have them saysh'ma,the Jewish creed: "Hear O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One." They're all still young, but they could no more go to sleep withoutsh'mathan without a pillow. It gives them comfort and closure on their day. Now, I don't pretend to think that my children won't intermarry because they say a Jewish prayer before nodding off. But in this way and in hundreds of others, I have given them a practice, a ritual, that reminds them they are Jewish -- and not just in synagogue but in school, in the playground, at home, in the kitchen, and even in bed.

In recent years, several authors, from Alan Dershowitz to Herman Wouk, have written about a crisis in American Jewry. While Jewish political and economic power appears secure, our numbers are shrinking; "disappearing" is Dershowitz's word. The intermarriage rate -- as high as 52 percent marry out of Judaism, according to the 1990 Jewish Population Survey -- shows no sign of reversing its upward trend, and our birthrate is below the replacement rate. Several solutions have been advanced. For some, the solution is to open up Judaism by relaxing its rules and making conversions to the faith easier. Others say, target efforts toward the non-jewish spouses of intermarried couples to bring them into Judaism. Others say, concentrate instead on the "core Jews" -- those-already members of the faith; build walls and fortify the faithful. Still others say, strengthen Jewish community centers where Jews can both study and socialize; others say, concentrate on improving and building synagogues. Others say that a fund must be supported to guarantee that every Jewish teen gets a trip to Israel; clearly, it is an experience that ties One to the land and the people. Still others talk about strengthening Jewish educational and Social programs for college youth.

I say, start simple. Do a ritual. Light a candle, visit a synagogue, attend a seder, celebrate life in a Jewish way. I believe there is something intrinsically valuable about Jewish observance. Take the Sabbath. In our house, we do not watch television or cruise the Internet or even talk on the telephone from sundown Friday until the stars come out Saturday night. For some this deprivation might seem like a punishment, but for me it is bliss. Our week is so filled with outside intrusions that it is a blessing to have one day without them. It is one thing to do that alone, or even as a family, but to do it in connection with others all around the world can transform and enrich.

YOU DON'T HAVE TO DO IT ALL

To my mind, it is not necessary to shut out all intrusions; even dropping one of them has its benefits. Turn off the television, and you just might finish that book you've been reading. Forget the telephone, and you just might spend more time at the dinner table talking to your family and guests.

I've spent my life observing Jews. As a child from a divorced family, I grew up at the tables of my aunts and uncles, in kosher hotels with one parent or the other, and in the synagogue, which often served as a home away from home. I've always been a student of the many variations in religious practice. In my twenty years, at theNew York Times-- ten of them spent covering religion -- I made a living out of watching these different ways of practicing Judaism. I covered New Age Jewish retreats, staid rabbinical conventions, and exuberant Hasidic gatherings known asfarbrengens.In addition, with this book in mind, I've conducted interviews with hundreds of Jews about their religious practices -- both on the Internet and in person -- in every denomination and in every region of the country. From all my years of observing Jews, I find one common thread: Jews are not consistent. Jews pick and choose from among the wide panoply of religious practices. In the words of the late Jacob Rader Marcus, the preeminent historian of American Jewry, who died in 1995 at the age of ninety-nine: "There are six million Jews in America and six million Judaisms."

Jews are not alone in their selective observance. American Roman Catholics, in fact, have a name for it: Cafeteria Catholicism. The image is of Catholics walking down the line with their cafeteria tray, taking what suits them. Some will agree with the Church on birth control but not on abortion, some will want to see women as priests but not gays. Many revere the office of the Pope but vehemently disagree with the man in office.

Instead of Cafeteria Catholics, we are Smorgasbord Jews. No orderly cafeteria line for us. I use the term smorgasbord because the Jewish choices are so much greater. Traditional Judaism makes demands that Christianity, from its very start, dismissed: circumcise, eat only kosher meats, pray three times a day, don't mix milk and meat, don't work on the Sabbath, and on and on. American Jews come to the great table of jewish observance and take what best suits them. No two buffet plates are the same.

There are Jews who keep kosher at home but not-outside the home. Some observe the Sabbath by not working, and others keep it by going to synagogue. There are those who observe neither the kosher laws nor the Sabbath, but wouldn't dream of eating bread on Passover. Some won't keep any rituals but wouldn't think of buying a German car, listening to a Wagner opera, or reading Ezra Pound.

Even the Orthodox are subject to these variations. There are those who eat kosher and those who eat onlyglattkosher (a higher level of kosher supervision). Some Orthodox men go to their jobs wearing large black hats; others go bareheaded. There are some married Orthodox women Who cover their hair all the time -- some with wigs, others with hats -- and there are others who cover their hair only in the synagogue. There are Orthodox men who will not shake hands with women other than their wives, and there are those who do. Some go to synagogue for prayer twice a day; others go only on Saturdays and festivals.

One of the nation's leading sociologists of Judaism, Dr. Bethamie Horowitz, has conducted hundreds of in-depth interviews with Jews around the nation. Getting a precise picture of Jewish practice is difficult, she said, because Jewish religious practice is fluid and idiosyncratic, and reinvents itself constantly throughout the life of the believer. Dr. Horowitz added, "We need to widen the way we define Jewish identification to include the idiosyncratic things people relate to Jewishly."

REACHING FOR THE HOLY

I like to think of these inconsistencies as the Jewish attempt to reach for the holy. As we stand at the smorgasbord we take the items that are most meaningful to us, and that will make us better Jews. All of this makes Jews a very quirky people. There is no single way to be Jewish in America today. Let me give some examples from my "quirk file":

* Joe, a high school teacher and a big Red Sox fan from Boston, always has a hot dog on opening day at Fenway. Hot dogs at Fenway are not kosher, but that doesn't bother Joe, who considers himself an American first and a Jew a distant second. One year, however, when opening day landed on Passover, Joe bought his hot dog, took it off the bun, and put it on a piece of matzah he had brought along just for that purpose.

* Phil works for a major weekly magazine that goes to press on Saturdays. He can't observe the Sabbath in the traditional manner, so he makes his own -- beginning Monday night; for twenty-five hours, he does not work.

* Sam is an orthodontist with a busy practice in New Jersey. He neither prays, goes to synagogue, nor keeps any ritual laws, with one exception. Every morning, he puts ontzitzit,the four-cornered fringed undergarment worn by pious Jews. He wears the garment all day while he sees patients and while he eats his non-kosher meals. Why does he weartzitzit?"I feel naked without them," he Says.

* Katherine, a convert to Judaism, can't fast on Yom Kippur. She gets sick if she doesn't eat. So she spends the day with a fast of another kind: she doesn't speak for twenty-five hours.

* Charlie and his wife, Susan, do not keep kosher. But on the Sabbath they never eat bacon or shellfish. "It's our way of keeping Shabbos," Charlie explains.

* The Weinstein family in Detroit keeps a kosher home; there are separate dishes for meat and milk. But there is also a third set -- Chinese -- which they use only for non-Kosher takeout.

All of these are true stories; about real people. What has been changed here are their names. In fact, the vast majority of them did not want their names used -- they consider these quirky practices to be private. Several admitted to being downright ashamed at their behavior, but for very different reasons. In some cases they felt they were doing too little; in other cases they felt they were doing too much. Perhaps the most poignant story for me came from my friend Bill (not his real name). Bill, a book editor, is not otherwise observant on a daily basis, but before he goes to sleep each night, he whispers thesh'ma."I don't even think my wife knows," said Bill. "It's my own little private prayer."

I had known Bill for decades and never knew this about him. As a regularsh'masayer myself, I felt a new connection. "Do you say it with your kids?" I asked hopefully. "No," he said. "I never thought of it."

What has happened is that religious idiosyncrasies have gotten such a bad name that people don't want to talk about them, let alone pass them on to their children. I know this mind-set; I was brought up with it. The Orthodox rabbis of my youth did not subscribe to the more popular notion we find today that Judaism is a matter of choice for both converts and those born Jewish. They spoke about the "yoke of the kingdom of heaven," an obligation to follow the precepts of Torah right down to rigorous daily observances. Feeling good was not part of the system. To allow people to do what they felt good about Jewishly was to invite a kind of religious free-for-all that allows people to pick and choose what feels good to them.

Today, even some outside of the Orthodox world worry about this kind of anarchy. Writing recently inCommentarymagazine, Jack Wertheimer, provost of the Conservative Jewish Theological Seminary, warned of those who advocate a "Judaism without limits," where a variety of choices and practices are incorporated into Judaism simply because they are trendy or they feel good. "Instead of setting clear lines," he wrote, "they enjoin Jews to lower the barriers between Jewish and non-Jewish religion....This way lies not pluralism but anarchy, and self-extinction."

I'm not advocating extinction, but I do think a little anarchy can be healthy. Being Jewish is about feeling good. It is about finding meaning. For some, that might mean the ArtScrollShabbos Kitchen Guide,but for others, it might mean eating lox and bagel or even a non-kosher hot dog on matzah. It might mean not talking on Yom Kippur, or having three sets of dishes, or saying thesh'masilently on your bed.

The young assistant rabbi in my Manhattan Orthodox synagogue might not put it the way I do, but he, too, sees virtue in idiosyncratic practice. "Judaism gives you 613 opportunities to find God," said Rabbi Yair Silverman, referring to the 613mitzvot,or commandments. "For each one you do, you do good."

"People are afraid of looking like hypocrites" by observing some laws and ignoring others, Rabbi Silverman added. "But they shouldn't be afraid. You should strive to be as great a Jew as you can be. Inconsistencies are part of human nature." He noted that the Jewish festivals, periods during which greater ritual observance is required, are meant to "highlight the extremes." The festivals "modulate the monotony of everyday life," he explained. "You don't live at the extremes. You climb to the top of the mountain to see the view. But you don't necessarily stay there."

Throughout this book, in sections labeled "variations on a theme," I will give other examples of how Jews live their Judaism -- on their own terms. I will describe both what the tradition demands and what people actually do in their lives. My purpose is to elevate these practices and show how indeed they are all efforts to reach for the holy. Only if people are proud of them and have confidence in their idiosyncrasies will they endure.

WHERE DOES ONE BEGIN?

I believe that quirks reveal a desire on the part of American Jews to act in a Jewish way. While some may ask why they go to so much trouble, I wonder why they don't do more. Why doesn't Joe find a kosher hot dog? Why doesn't Sam go to synagogue? Why doesn't Bill say thesh'mawith his children? One rabbi told me that fear keeps many American Jews from performing rituals -- fear of doing the wrong thing, fear of sitting in the wrong place, fear of not knowing the words to the prayer. I understand this fear. Many Jews, well educated at the best universities, know Homer and Shakespeare but never read Maimonides. They can order food at the best French restaurants but can't read the Passover haggadah. We've forgotten the lessons of the Angel Gabriel. Gabriel reminds us that we have a relationship with ritual that goes back to our very beginnings. And whether or not we want to believe that all that is part of our distant past, Gabriel reminds us that there are mentors and teachers and stories that can help us make Judaism a greater part of our lives.

My hope is to be one of those mentors -- Gabriel's helper, if you will -- by making Jewish ritual accessible for American Jews and others interested in the faith. I will explain what the tradition demands, what the rabbis allow, and what people actually do in their daily practice. In these pages, I offer a "toolbox" of Jewish ritual that I hope readers will open, explore, and experiment with. These are not magic incantations or rites. Lighting a candle is no more meaningful than picking up a hammer. What is important is how you use that candle to build a Sabbath experience in your home. Ritual has the power to take the mundane and make it holy and, with time, open the heart.

To my mind, the greater debate on the Jewish destiny can wait. What is important is to start with acts that proclaim that Jews are a people with a land, a history, wisdom, and a heart. Doing ritual acts makes those ideas concrete and connects us with our past, our God, and our people.

Copyright © 2000 by Ari. L. Goldman

CHAPTER ONE

Beginnings

Judaism, from its beginnings, has been obsessed with fertility. Abraham, as the first Jew, knew that his discovery of the Oneness of God would amount to little if he did not have a child with his wife, Sarah. But "Sarah was barren," Genesis reports; "she could not give birth." Yet, God promises Abraham offspring "as numerous as the stars" and "as plentiful as the sands of the earth." When three visitors appear and promise Abraham a child through Sarah, she laughs with a mixture of disbelief and delight. It is a great moment -- one of the only times in the Bible that anybody laughs. The name she gives her son, Isaac, comes from the Hebrew tzechok, laughter. Isaac's wife Rebecca is also barren, and so is Rachel, the favorite wife of Jacob. But in response to their prayers, God intervenes there too; they bear children and, through them, the Jewish people.

In Judaism, the birth of a child is a fulfillment of a dream. In a sense, every Jewish child is an Isaac, worthy of being welcomed with laughter and celebration. In birth ceremonies, we give the child a Jewish identity by giving a Jewish name. In the case of boys, the identity is cut into the flesh in the act of the brit, or circumcision. Boys are named at their brit; girls, either in a special naming ceremony, known as a simchat bat, or when one or both of their parents are called to the Torah in the synagogue. The formal naming is so significant that traditionally the name of the child is not revealed until the moment of the religious ceremony. For that reason, you will often see bassinets in maternity wards with a last name and the word "Baby" filled in where the first name should be, as in "Baby Rabinowitz." These are often the babies of Orthodox parents who are waiting for the formal ceremony to give the name. The official Hebrew name, usually an analogue of the English (Yosef for Joseph, Rivka for Rebecca) is completed not with the family name but with the name of the parents. Thus, it would be Yosef ben Avraham V'Sorah (Joseph the son of Abraham and Sarah), or Rivka bat Yitzchak V'Rachel (Rebecca the daughter of Isaac and Rachel). While it is not required, children are often named after relatives, although there is a difference of opinion as to which relatives are so honored. Jews of Middle Eastern origin name children after their living or deceased relatives; most European Jews name them only for relatives who have died.

A name is a powerful legacy. Our youngest child, Judah, was born just five weeks after the death of my mother, Judith Goldman, from cancer at the age of seventy. Giving Judah my mother's name provided enormous comfort -- and a lasting connection to her. My mother would want to be remembered first as a religious woman, but she also believed in adventure, in love, and in life. She had two homes, one in Manhattan and the other in the tony Connecticut town of Westport. On Saturdays, you'd find her with her head covered in the women's balcony of the Fifth Avenue Synagogue in Manhattan, but during the week, she'd be driving around Westport in her white convertible, the top down and the radio blaring. Judah, an energetic preschooler who does cartwheels down the halls of our Manhattan apartment, has much of her spirit. Sometimes I even find myself calling him "Judy."

The Brit

Boys are circumcised on the eighth day, just as Abraham circumcised his son Isaac, some four thousand years ago. "This is my covenant," God tells Abraham in Genesis, "which you shall keep, between me and you and your offspring after you: Every male among you shall be circumcised...when he is eight days old."

A circumcision can be postponed if the child is sick or otherwise at risk, such as in the case of a premature baby, but the tradition to perform the ritual on the eighth day is strong, even if the eighth day turns out to be the Sabbath or Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the year. To be considered a ritual act, the circumcision -- the removal of the foreskin that covers the penis -- must be done in a religious ceremony. A circumcision performed by a doctor in the hospital without the attendant blessings and intentions is not considered a religious rite. Religious circumcisions are often performed by a trained practitioner, known as a mohel, at a celebration that is held in either the home, the hospital, or the synagogue.

The popularity of circumcision, once a standard practice in America for most of the twentieth century, is apparently on the wane. Thirty years ago, about 90 percent of boys in the United States were circumcised; the most recent figures from the National Center for Health Statistics show that the rate has fallen to 62 percent. The American Academy of Pediatrics, which for decades favored the procedure on the grounds that it had medical benefits, reversed itself in 1999. "Circumcision is not essential to a child's well-being at birth," the group, with fifty-one thousand members, said.

Individual doctors take positions one way or the other. Some health authorities say that to circumcise is to ensure a cleaner, healthier male who will have greater pleasure during sex. Circumcision is said by these authorities to reduce the risk of contracting urinary tract infections. Uncircumcised males have a higher incidence of penile cancer as well as a higher risk of contracting HIV infections and other sexually transmitted diseases, they say. Other health authorities say that the traumas and dangers of such surgery are so great that any positive by-products are to be discounted. The risks of infection can be effectively reduced by proper hygiene. Besides, they add in direct contradiction of circumcision advocates, sex is better with a foreskin.

"For every health argument, you can find a counterargument," said Rabbi Jeffrey Kamins of Sydney, Australia, who was on sabbatical in Israel with me. His congregation is Reform, but still, most members opt for circumcision. "Every once in a while you get a couple who doesn't want one. I go through the arguments with them. I'm not going to say that it's painless. It hurts, but isn't it better to do it now than for your child to grow up and want one? It's a lot simpler in infancy. As for trauma, ask any Jewish man if he's had surgery, and chances are, unless he's had his appendix out, he'll say no. Who remembers their brit? There are no lasting harmful effects. Sure, it's tough to do, but part of being a parent is making tough choices."

It is significant that a Reform rabbi advocates for brit. One hundred fifty years ago, in the early days of the Reform movement, some of its theologians argued that circumcision should be rejected as a bloody throwback to antiquity. In 1843 in Germany, where Reform Judaism was founded, some of its leaders attempted to abolish the practice on several grounds, including the fact that there is no parallel initiation rite in Judaism for girls. Abraham Geiger, an early Reform leader, described circumcision as "a barbaric, bloody act, which fills the father with fear."

Over the years, Reform Judaism softened its opposition and today recommends that parents circumcise their sons. In Reform and Reconstructionist Judaism, however, brit is not required, as it is among the Orthodox and Conservative branches.

Rabbi Kamins tells the parents that whether or not they opt for the brit, "your child will still be Jewish," an opinion shared even by the Orthodox. But he adds, "Think about where your son stands regarding the Jewish community." To be a Jewish male is to be circumcised. In ancient times an uncircumcised male could not fully participate in the seder by eating the Passover sacrifice. Some religious authorities today say that someone without a brit should not be called to the Torah in synagogue.

Both of those acts -- eating at the Passover sacrifice and being called to the Torah -- demonstrate one's attachment to the Jewish people. "Brit links the child to the Jewish community," said Rabbi Elie Spitz, the head of a Conservative congregation near Irvine, California. "It's not simply a tribal act, but a statement of linkage to God. What makes the Jewish people a religious people is that we live our life moments in God's embrace. In this moment of brit the child is given an identity in covenant with God."

Creating a child involves not only mother and father, he adds, "but a presence of God that makes the moment transcendent, providing miracle and meaning. At a brit, all these things come together: the wonder and fear of being a parent, the sense of discovery of who this child is, and the wonder that out of an act of sex comes a human being."

For me, brit is not only a statement of Judaism but a declaration that one is not a Christian. God's covenant with Abraham still stands despite what was once a pervasive Christian theology that said that the Jews lost the covenant because they failed to live up to it. What's important, Paul says in the New Testament book of Romans, is "to be circumcised in the heart, not in the flesh."

For a Jew to affirm circumcision at the beginning of the third millennium, then, means much as it did four thousand years ago when Abraham circumcised Isaac. Back then, Abraham was just breaking with his clan; but today, the act of ritual circumcision is a counterpoint to Christianity. To circumcise today is to proclaim publicly and boldly that we are still circumcised in the flesh, bound to the everlasting Covenant of Abraham.

The Ceremony for Boys

Preparations for the ritual begin when the baby is born. The parents have to find a mohel and decide whether to hold the circumcision in the home or the synagogue. Arrangements must be made for the seudah, a light celebratory meal that follows the circumcision. A time must be set. By tradition, the brit is held early in the morning on the eighth day.

On the night before the brit, some families gather around the newborn's bassinet to observe a special night of watching, in German Wachnacht. In Jewish folklore -- a world populated by spirits, some of them good, most of them bad -- the uncircumcised male is particularly vulnerable. He does not yet bear the sign of the covenant and therefore can fall prey to the mightiest female demon, Lilith. Sometimes identified as the first wife of Adam before the creation of Eve, Lilith is said to prey on males, women in childbirth, and especially newborn babies. Even a full-grown man should be wary of sleeping alone, lest Lilith seduce him. From his nocturnal emissions, she bears an infinite number of demonic sons.

In some Sephardic homes, candles are lit throughout the house and incense is burned. Among the Jews of Greece, the mother stays awake all night. Among Ashkenazic Jews, the mother sleeps, but the father stays up late into the night studying sacred texts. Brothers and sisters will sing lullabies to comfort the infant. Among the Jews of Yemen, a white lamb is slaughtered the morning of the brit, both as a symbolic sacrifice in which one soul is given for the safety of another and, on a more practical level, to provide food for the celebratory seudah. Most American Jews will just order lox and bagels. The brit is bloody enough without a slaughtered lamb.

A brit is a community celebration. Traditionally, one does not invite friends to a brit but just informs them that the brit is taking place. The parents might call and say "The brit will be held Wednesday at eight," rather than "You're invited to join us." There's no time for RSVPs. It is understood that all are welcome. According to the Talmud, the religious obligation to circumcise falls on the father, just as it fell on Abraham. If the father is unable to perform the rite, it is the responsibility of the Jewish community; if the community fails to step in and the child grows to manhood without being circumcised, the obligation falls on the man himself to fulfill the commandment.

It is a tough thing to do, to cut the foreskin of your son, shed his blood for what you believe. Here, too, the ancient figure of Abraham serves as an inspiration. Abraham fulfilled his obligation to circumcise his son Isaac, but God wanted more. The same God who had promised to multiply Abraham's children like the sands and the stars, later in Genesis tells Abraham to sacrifice his beloved Isaac. "Take your son, your only son Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt offering upon one of the mountains of which I shall tell you." Abraham wastes no time in the pursuit of God's will. "So Abraham rose early in the morning," the story continues. He takes Isaac, a knife, and firewood, and marches to the top of Mount Moriah and prepares the sacrifice. As everyone knows, Abraham was lucky. An angel stayed his hand.

I think every Jewish father, in the moments before his son's brit, secretly wishes for another visitation by God's angel. Happily, Jewish law allows for a surrogate in the person of the mohel, a professional with a steady hand specially trained in the art of circumcision. In the traditional ceremony, the mohel, with the scalpel in his hand, turns to the father and asks, "Do you designate me as your messenger?" With the father's assent, the cutting begins.

The place that is cut is at once the most sensitive and most potent part of the male body. As in any operation, there is risk, but there is also great symbolism. The child is connected to Jewish history through the cutting of his reproductive organ, an organ through which he will some day pass his Judaism on to another generation. The moment of the brit, then, is a link between the Jewish past and the Jewish future.

To represent this continuity between the generations, older members of the family take a central role in the ceremony. The kvaterin, a grandmother or other senior member of the family, brings the baby into the room, passing the child from one relative to another until it reaches the sandek, the grandfather or other elder of the family. The sandek holds the infant during the operation but first gently places the child on a special chair called kesai shel Eliyahu, the chair of Elijah, symbolizing that, like Elijah, every child has the potential to bring the Messiah -- or to be the Messiah.

After the operation, a blessing is said over a cup of wine, and the baby is given a name. It is customary to dip a piece of gauze in the wine and let the baby suck; just a drop, I've found, always eases the baby's crying. A prayer is then offered that the child grow "to Torah, the wedding canopy, and good deeds." The prayer sets an agenda for life and reminds me of what one older friend once told me about being a parent. "You're not raising children," he said. "You're raising adults." The brit is the first step.

The Ceremony for Girls

A baby girl's entry into the Jewish community was traditionally marked by her father's being called to the Torah in the synagogue on the Sabbath after the birth. The father would first make a blessing for the health of the girl and the recovery of the mother and then bestow a Hebrew name on the newborn. The mother and daughter were rarely present.

Since the advent of the women's movement in the 1970s, ceremonies celebrating the birth of a daughter have become more popular. But they didn't have to start from scratch. In the traditional Jewish communities of Yemen, for example, women for centuries held a service called the zebed habat, the Gift of a Daughter. Women of the community would come and sit with the mother and child to admire both with songs of praise. Women would bring gifts of incense and candles and fertility symbols, such as live chickens and "star water" (water exposed to the heavens for seven nights). This was to ensure the continued fertility of the mother and the eventual fertility of the newborn.

Today's ceremonies for girls are focused less on fertility, and both men and women participate. Known as the simchat bat, the Joy of the Daughter, the ceremony is a time to welcome the newborn into the community of Israel, both male and female. The practice can today be found in all the branches of Judaism.

Rather than hold the simchat bat on the eighth day, a time when the mother may not have fully recovered and the infant is still fragile, families decide on the most convenient time, usually within a month of the birth. Some will wait for the beginning of the next Jewish month, known in Hebrew as Rosh Hodesh, a time that coincides with the cycle of the moon, which is of special significance to Jewish women. The new moon is traditionally seen as a special holiday for women, whose bodies are biologically in tune with the cycles of nature.

Simchat bat ceremonies by their very nature are more relaxed and spontaneous than the brit ceremony. I've seen grown men faint and most men admit to feeling a little weak at the knees at the sight (or even mention) of a circumcision. The baby boy's cry when he is cut has no echo at the simchat bat.

While the liturgy for the brit ceremony can be found in any prayer book, the ceremony for girls is constantly updated. The Jewish feminist Arlene Agus has collected a whole file of these ceremonies, some of them handsomely printed on glossy paper but most written by hand and photocopied for the participants. A ritual guide published by the Jewish Women's Resource Network, a national group based in Manhattan, suggests that the ceremonies include songs, blessings, wine, and a celebratory meal. "And not to be forgotten," the guide adds, "the ceremony should be fun." Rabbi Kamins told me that in his community in Sydney, the women bring their Sabbath candlesticks to the simchat bat and light them to serve as a backdrop to the ceremony. The newborn is passed from woman to woman, but instead of being handed over for surgery, she is placed on a bed of flowers and is formally named by her parents.

Haviva Ner-David, an Orthodox Jewish feminist who lives in Israel, took her newborn daughters to the mikveh, the ritual bath, to mark their entrance into the Covenant of Abraham. She based the custom on the commentary of Rabbi Menachem ben Solomon, who lived in Provence in the late thirteenth century. Rabbi ben Solomon, known as the Meiri, suggested that Abraham's wife, Sarah, immersed herself in the mikveh as a sign of her connection to God when Abraham was circumcised. In her book Life on the Fringes, Ner-David writes: "There can be no more appropriate ritual to bring our daughter, the product of our love and partnership with God, into the Jewish people. There can be no more appropriate means than mikvah, the ritual bath in which women throughout Jewish history have been immersing themselves after the cessation of their menstrual flow, for me to initiate my daughter into Jewish womanhood, with all its joys and conflicts, trials and responsibilities."

Ner-David was nervous about putting her newborn underwater, but was assured by her doctor and her husband that it would be all right. She concludes: "I blew into her face so that she would instinctively hold her breath, and then I dunked her.... I put what is most precious to me in the hands of God."

The trip to the mikveh might work for Ner-David, but some rabbis feel that it smacks of Christian baptism and should be avoided. An alternative that I heard about at a meeting of Orthodox feminists involves holding a special ceremony for the infant girl during which her ears are pierced. The act of cutting the ear has echoes in the Bible -- in Exodus, a Jewish servant is permanently bound with such an act to his master. In this context, piercing the ears can be a sign of the newborn's attachment to God. And such a ceremony outdoes the brit, if only because there are two ears.

A Sign of the Covenant

The Bible refers to the mark of male circumcision as "ot brit" -- a sign of the covenant. The guide from the Jewish Women's Resource Network comments: "Since women do not have a permanent sign of the covenant cut into them, some parents like to supply their daughter with an external sign." The simchat bat is a time to make a public presentation by the parents of a gift that will be a reminder of the day. Among the suggested gifts are Sabbath candlesticks, a silver wine goblet, or a Hebrew Bible.

One enduring gift that parents can give a child, boy or girl, on the day of the baby's naming is a letter in which they detail their decision to give the child a particular name. Parents often use the occasion of the ceremony to give a short talk on the name. They tell the assembled who the child is named for or what attributes of the name they especially identify with. Rabbi Stuart Kelman, who leads a Conservative congregation in Berkeley, California, urges parents to write down their thoughts in a letter and save it for the child. Who wouldn't love to have such a letter from his or her parents? he asks. Each new life brings a hope so pure and horizons unlimited. Jewish ritual helps you capture and preserve those feelings.

*****

The Basics

*****

Biblical Origins "Every male among you shall be circumcised. And you shall be circumcised in the flesh of your foreskin, and it shall be a token of a covenant between Me and you. And he that is eight days old shall be circumcised among you, every male throughout your generations" (Genesis 17:11-12).

The Operation The foreskin is surgically removed from the head of the penis.

Vocabulary In Hebrew, the circumcision is called a brit, which literally means covenant. The man who performs the brit is a mohel (plural: mohalim). A woman is known as a mohelet (plural: mohalot). If a man is already circumcised surgically and wants a ritual circumcision as well, a mohel makes a symbolic incision in the head of the penis in a procedure known as hatafat dam brit.

Purpose The Bible is silent on any motive. In Jewish history, the brit has served to distinguish Jews from others. The operation was also a deterrent against conversion into Judaism. Some see in the act a message of sexual restraint.

First Recorded Circumcision Abraham, at age ninety-nine.

Second Ishmael, at age thirteen.

Third Isaac, at eight days.

Code of Jewish Law (Shulchan Aruch) It is a father's duty to have his son circumcised. If the father does not act, the community must step in and ensure that the boy is circumcised. If the boy grows to adulthood without a circumcision, the duty falls on the man himself. When possible, the circumcision should be done on the eighth day of life. If the brit would endanger the child, the operation can be postponed. The ritual is so sacred that it can even be performed on the Sabbath if it is the eighth day.

Blessings The father (or sometimes both parents) makes two blessings, acknowledging that he is initiating this act to bring the child "into the covenant of Abraham our father." Those gathered respond: "Even as he has been introduced into the covenant, so may he be introduced to the Torah, the marriage canopy, and to a life of good deeds." The mohel makes two additional blessings, one on the act of cutting and another on a glass of wine.

Honors Sandek, a man who holds the child during the circumcision. Kvaterin, a woman who presents the infant for the ritual.

Who Can Circumcise According to tradition, a Jewish man. If there is no one else available, the tradition allows a woman to do the brit.

Modern Innovations The simchat bat celebration for girls, a new custom found in all the branches of Judaism. Among the non-Orthodox, there is also a movement to involve women in the boy's circumcision. Women (usually pediatricians or gynecologists) are trained in the non-Orthodox movements to act as mohalot.

Copyright © 2000 by Ari L. Goldman

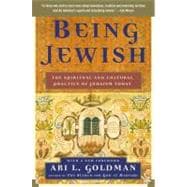

Excerpted from Being Jewish: The Spiritual and Cultural Practice of Judaism Today by Ari L. Goldman

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.