Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

| Illustrations | ix | ||||

| Preface | xi | ||||

| Author's Note | xiv | ||||

| Prologue | 1 | (235) | |||

|

4 | (19) | |||

|

23 | (41) | |||

|

64 | (21) | |||

|

85 | (29) | |||

|

114 | (33) | |||

|

147 | (6) | |||

|

153 | (30) | |||

|

183 | (12) | |||

|

195 | (41) | |||

| 10. In the Sight of the Heathen | 236 | (27) | |||

| 11. The Second Week | 263 | (33) | |||

| 12. The Legacy | 296 | (23) | |||

| Postscript | 319 | (1) | |||

| Acknowledgements | 320 | (3) | |||

| Notes | 323 | (12) | |||

| Bibliography | 335 | (10) | |||

| Index | 345 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

Sporting Spirit

With its grand classical façade, the town hall in Barcelona makes a suitable setting for momentous decisions. Gathered there on the morning of Sunday, 26 April 1931, were twenty men, all of whom had breakfasted well and were ready to discuss the most important matter on the agenda of their two-day meeting—the venue for the 1936 Olympic Games. The men were members of the International Olympic Committee, and this, their twenty-eighth annual meeting, was chaired by the committee's president, the Wfty-Wve-year-old Count Henri de Baillet-Latour. The Belgian had been a member of the IOC since 1903, just nine years after it had been created to establish the Wrst of the modern Olympic Games in Greece in 1896. A former diplomat and a keen horseman, Baillet-Latour had successfully organised the 1920 Olympics in Antwerp, a feat that had been regarded as extraordinary as he had only a year to accomplish it in a country that had been ravaged by war. Tall, with balding white hair and a large but trim moustache bristling under a long nose, Baillet-Latour commanded much respect from his fellow members of the IOC.

Also present were three men who hoped to gain much from the meeting. Their names were State Excellency Dr Theodor Lewald, Dr Karl Ritter von Halt and the Count de Vallellano. Lewald and von Halt were both German members of the IOC, and they felt conWdent that Berlin, after years of lobbying, would be awarded the prize. Nevertheless, Vallellano, a representative of the Spanish Olympic Committee and a powerful Wnancier with his own palace in Madrid, was hopeful that the IOC members would award the 1936 Games to Barcelona.

Although Berlin and Barcelona were the two front-runners for the prize, there were two other potential candidates for host city—Budapest and Rome. After an introduction by Baillet-Latour, the Wrst members to speak were two Italian members of the IOC, General Carlo Montu and Count Bonacossa. To the relief of the Germans and the Spaniard, they told the meeting that 1936 was not the right time for Rome to host the Games, but they begged the committee to consider the city at some future date. The next to speak was the Hungarian, Senator Jules de Muzsa, who instead of lobbying for his capital spoke in favour of Berlin, much to the delight of Lewald and von Halt.

Lewald then addressed the meeting. For him, that Sunday morning was the potential culmination of nearly two decades of intense eVort to get the Games staged in Germany. A member of the IOC since 1924, Lewald had also been head of the German Organising Committee that had been planning the 1916 Olympics, which were awarded to Berlin at Stockholm in 1912. The Germans had set to work immediately, and had constructed a magniWcent stadium outside Berlin that had been dedicated by the Kaiser in 1913. Surprisingly, the outbreak of war in 1914 did little to damage the chances of the Games being held in Germany. 'In olden times it happened that it was not possible to celebrate the Games, but they did not for this reason cease to exist,' Baron Pierre de Coubertin, the founder of the modern Olympics and the then president of the IOC, declared in the spring of 1915. In April, the Germans announced that the Games would simply be delayed until the end of the war, a decision agreed by the IOC.

On the 22nd of that month, however, a grey-green cloud was observed by 8,000 French colonial soldiers entrenched north of Ypres in northern France. The cloud was in fact a truly terrifying weapon. It was chlorine gas, and its sinister, billowing appearance caused the soldiers to Xee. The Germans, wary of their own gas, failed to capitalise on the French retreat and the gap in the line was quickly reinforced by Allied troops. The deployment of those Wrst few tons of chlorine changed the nature of the war, however, and soon poison gas was used on both sides. As a result of the war losing its 'gentlemanliness', Coubertin Wnally felt obliged to cancel the Games.

After the war ended, Lewald was to encounter more disappointments, as Germany was forbidden from taking part in the Games of 1920 and 1924. Nevertheless, along with Dr Carl Diem, his sidekick on the German Olympic Committee, he persisted in lobbying the IOC, whose new head, Baillet-Latour, was more amenable to their approaches. Lewald's eVorts paid oV. In 1928, Germany once more competed in the Olympics. Her performance at Amsterdam was stunning; the country came second only to the United States in the tally of medals. With eight gold medals, seven silver and fourteen bronze, Germany had Wrmly re-established herself as an Olympic power. Naturally, Lewald was determined to capitalise on the German success. In May 1930, the IOC held its congress in Berlin. Setting the tone for the gathering, President Hindenburg declared that 'physical culture must be a life habit'. But the meeting was more of a showcase for Lewald than the ageing president. If Lewald could suYciently impress the visiting Olympic dignitaries, then there was a good chance that Berlin might soon host the Games. Lewald was mercenary, even reminding the delegates that it was thanks to the work of German scholars that so much was known about classical Olympism. Rooted in antiquity, Germany was the natural home for the Games, he claimed.

Lewald drew on the same themes at the meeting that Sunday morning in April 1931. As a former under-secretary of state, the seventy-year-old Lewald was used to the sophisticated parley of the committee room. He made the case for Berlin impressively, with no need to draw on the smooth charm of his colleague, the handsome Wnancier and war hero von Halt. Lewald said that Berlin deserved the Games, not least because it had been denied them in 1916, and also because Berlin, being in the heart of Europe, would attract far . . .

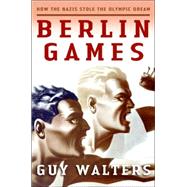

Berlin Games

Excerpted from Berlin Games: How the Nazis Stole the Olympic Dream by Guy Walters

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.