What is included with this book?

| Foreword | |

| Introduction | |

| "Verities" | |

| "'See the Pyramids Along the Nile'" | |

| From "Couple from Hell" | |

| "A Worldly Country" | |

| "Speech in a Chamber" | |

| "Letter from My Ancestors" | |

| "You Must Have Been a Beautiful Baby" | |

| "Apologia to the Blue Tit" | |

| "Rhetorical Figures" | |

| "Sestina for the Newly Married" | |

| "Our Generation" | |

| "Toward Some Bright Moment" | |

| "'Please Don't Sit Like a Frog, Sit Like a Queen'" | |

| "The Land of Is" | |

| "Souvenir" | |

| "List of First Lines" | |

| "For My Niece Sidney, Age Six" | |

| "Bust of a Young Boy in the Snow" | |

| "The Death of Winckelmann" | |

| "My First Mermaid" | |

| "The Curve" | |

| "Monsieur Pierre est mort" | |

| from "Sects from A to Z" | |

| "Bird, Weasel, Fountain" | |

| "Refusal to Notice Beautiful Women" | |

| "On the Way to the Doctor's" | |

| "The Problem of Describing Color" | |

| "Hour" | |

| "Talk" | |

| "My career as a director" | |

| "The Ferry" | |

| "At Gettysburg" | |

| "Just a second ago" | |

| "Seventeen Ways from Tuesday" | |

| "The Laws of Probability in Levittown" | |

| "Found" | |

| "Sally's Hair" | |

| "Tonight" | |

| "Double Abecedarian: Please Give Me" | |

| "Demographic" | |

| "That's Not Butter" | |

| "Eyes Scooped Out and Replaced by Hot Coals" | |

| "Blenheim" | |

| "Albert Hinckley" | |

| "Briefcase of Sorrow" | |

| "The Poet with His Face in His Hands" | |

| "Small Town Rocker" | |

| "The Sharper the Berry" | |

| "Race" | |

| "Two Poets Meet" | |

| "The Great Poem" | |

| "Roadside Special" | |

| "The Other Woman's Point of View" | |

| "Discounting Lynn" | |

| "Thin" | |

| "A Phone Call to the Future" | |

| "Memoir" | |

| "Misjudged Fly Ball" | |

| "House of Cards" | |

| Table of Contents provided by Publisher. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Foreword

by David Lehman

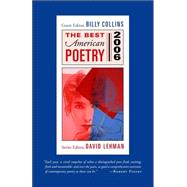

Back in 1992, when he made his first appearance inThe Best American Poetry, Billy Collins was a little-known, hardworking poet who had won a National Poetry Series contest judged by Edward Hirsch. He had supported himself for many years by teaching English and was, like many other poets, looking for a publisher. Charles Simic chose "Nostalgia" fromThe Georgia ReviewforThe Best American Poetry 1992and for the following year'sBest, Louise Glück selected "Tuesday, June 4th, 1991" fromPoetry. Others, too, recognized Collins's talent. The University of Pittsburgh Press began to publish his books in its estimable series directed by Ed Ochester. Radio host Garrison Keillor gave Collins perhaps the biggest boost of all by asking him to read his poems on the air. He did, and the audience loved what it heard. Collins grew popular. At the same time, it was understood that he was no less serious for having the common touch. Asked to explain his poetic lineage, he liked citing Coleridge's "conversation" poems, such as "This Lime-Tree Bower My Prison." And for all their genial whimsy, many of Collins's efforts have a decidedly literary flavor, with such subjects as "Tintern Abbey," Emily Dickinson,The Norton Anthology of English Literature, poetry readings, writing workshops, "Keats's handwriting," and Auden's "Musée des Beaux Arts." John Updike put it exactly when he described Collins's poems as "limpid, gently and consistently startling, more serious than they seem." In 2000, two publishers quarreled publicly over the rights to publish Collins's books, and theNew York Timesreported the story on page one. The unlikely success story reached its apogee a year after September 11, 2001, when Billy Collins read "The Names," a poem he had written for the somber occasion, to a rare joint session of Congress.

By then Collins had become a phenomenon. While remaining a member in good standing of the poetry guild, an entity with a purely notional existence whose members would theoretically starve for their art, he had regular contact with honest-to-goodness book-buying readers who were not themselves practicing poets. They numbered in the tens of thousands and made best-sellers of his books. He won a Guggenheim Fellowship and a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. His poems were published in respected journals such asThe AtlanticandPoetryand were chosen by the diverse quartet of John Hollander, Robert Bly, Rita Dove, and Robert Hass for four consecutive volumes ofThe Best American Poetry. In June 2001, Collins succeeded Stanley Kunitz as Poet Laureate of the United States, and I remember hearing people gripe about the appointment. Collins was regularly dismissed as an "easy" or "anecdotal" poet. It was then that I knew he had made it big. Harold Bloom has propounded the theory that poets fight Oedipal battles with ancestors of their choice, so that Wallace Stevens had to overcome Keats's influence as Wordsworth had earlier overcome Milton's. It sometimes seems to me that a different Freudian paradigm -- sibling rivalry -- may explain the behavior of contemporary poets, for the backbiting in our community is ferocious, and nothing signifies success better than ritual bad-mouthing by rivals or wannabes.

The story as I've sketched it broadly here illustrates more than one useful lesson. Probably the most important is that poetry has the potential to reach masses of people who read for pleasure, still and always the best reason for reading. Radio is a great resource for spreading the word, and attention from programs such as Keillor'sWriter's Almanac, Terry Gross'sFresh Air, and the interview shows of Leonard Lopate in New York City and Michael Silverblatt in Los Angeles is among the best things that can happen to a book or an author. Another lesson is that some poets share a resistance to popularity -- other people's popularity, above all -- though they might bristle if you called them elitist. It's a problem that afflicts us all to some extent. We say we want real readers, who buy our books not as an act of charity but as a free choice, yet should one in our party escape the poetry ghetto, we tremble with ambivalence, as if having real readers means a sure loss in purity. Inevitably the discussion turns to a question that seems substantive. What accounts for an individual poet's popular appeal? Does popularity result from (or result in) a loss of artistic integrity? What makes the lucky one's star shine so bright that it can be seen to sparkle even in the muddy skies of the metropolis, where industrial wastes have all but abolished the sighting of a heavenly body?

To the second of these questions, the answer is a simple no. Collins's readers came to him; he did not alter his style or his seriousness to curry anyone's favor. (It is, in fact, entirely possible that the poet setting out to be the most popular on the block stands the least chance of achieving that goal.) The answer to the other questions begins with the surface of Collins's poems, which is amiable, likable, relaxed. Even critics of Collins would concede that his poems have a high quotient of charm. He is, to ring a variant on a theme from Wordsworth, unusually fluent in the language of an adult speaking to other adults in the vernacular. Moreover, he insists on the primacy of the ordinary, as when he expresses contentment in "an ordinary night at the kitchen table, / at ease in a box of floral wallpaper, / white cabinets full of glass, / the telephone silent, / a pen tilted back in my hand." I would wager that Collins's ability to find and express contentment in the ordinary has contributed in a major way to his popular appeal. Wit and humor, traits of his verse, don't hurt. Above all, his poems make themselves available to the mythical general reader that book publishers crave. You don't need to have been an English major to get a Collins poem such as "Osso Buco" or "Nightclub." Such poems insist on a poetic pleasure principle. They are, to use a charged word,accessible. "Billy Collins's poetry is widely accessible," said Librarian of Congress James Billington in June 2001. "He writes in an original way about all manner of ordinary things and situations with both humor and a surprising contemplative twist." Collins himself has reservations aboutaccessible, a word that he says suggests ramps for "poetically handicapped people." He prefershospitable. But there's no dodgingaccessible, and in the introduction to his anthology180 More, Collins granted that the quality denoted by the word was what he looked for in a poem. An "accessible" poem, he wrote, is one that is "easy to enter," in the sense that an apartment or a house may be welcoming. "Some poems talk to us; others want us to witness an act of literary experimentation," he wrote, declaring his preference for the former and arguing that pleasure in poetry -- its paramount purpose, according to Wordsworth -- demands clarity.

The opposition between clarity and difficulty, or between communication and experimentation, is happily not absolute. Nor can we take it for granted that any of these terms has a fixed meaning that all can agree on. Accessibility -- as a term and, implicitly, as a value -- has been attacked recently by Helen Vendler inThe New Republic. " 'Accessibility' needs to be dropped from the American vocabulary of aesthetic judgment if we are not to appear fools in the eyes of the world," Vendler wrote in the context of defending John Ashbery, "with his resolve against statement bearing the burden of a poem." Yet it is of course conceivable, it is even perhaps inevitable, that a poem by John Ashbery should be among the seventy-five poems chosen by Billy Collins forThe Best American Poetry 2006. And so it has happened. Abstract discussion is one thing, poetic creativity and intuition is another, and it takes the former a long time to catch up with the latter. Let the debates continue. The poets themselves will make their choices, but they will do so on the basis of poems loved rather than positions held, rebuffed, or discarded.

There may be a structural antagonism between poets and critics, but at its best, criticism can make better writers of us, link poetry to its readership, and help build a community. The work of explanation, evaluation, and elucidation is there to be done. Unfortunately, much contemporary criticism is singularly shrill, sometimes gratuitously belligerent, even spiteful. I wonder where the rage comes from. Is it to overcompensate for the widespread if erroneous perception of poets as a band of favor-trading blurbists forever patting one another on the back? Or is the explanation simply that it is and always has been easier to issue summary judgments than to grapple with new art? I wonder, too, whether young poets flocking to MFA programs or working on their first manuscripts know what they're in for. It sometimes seems to me that the fledgling poet is in the position of the secret agent in Somerset Maugham'sAshenden, who gets his marching orders from a superior known only by his initial. "There's just one thing I think you ought to know before you take on this job," R. says. "And don't forget it. If you do well you'll get no thanks and if you get into trouble you'll get no help."

Perhaps when we review the reviewers, we should put a higher value on moments of mirth, such as Thom Geier ofEntertainment Weeklyprovided last year. Geier opined inventively that John Ashbery's "oeuvre is not unlike Paris Hilton's" but "much, much smarter." There is so much to admire in this formulation -- the word "oeuvre" bumping against that fussy "not unlike," and the double "much" -- that one feels like a killjoy pointing out the comic outrageousness of the comparison. In the same magazine Billy Collins was characterized as simultaneously the Oprah of poetry, "the best buggy-whip maker of the 21st century," poetry's answer to Jerry Seinfeld ("hilariously funny"), a "modern-day Robert Frost," and "like Rodney Dangerfield," a figure who "doesn't get much respect in some serious literary circles," in part because his work is, yes, "accessible." Well, whatever else he is, Billy Collins is a natural choice to edit this year'sBest American Poetry, and he has crafted an anthology that demonstrates the vitality of American poetry and showcases poems of wit, charm, humor, eloquence, ingenuity, and comic invention.

Every year I screen hundreds of newspaper articles touching on poetry, and there are always one or two items that linger longer in the memory. Two last year stood above the rest. One was in the obituaries for Jerry Orbach, an actor as skillful playing a cop onLaw and Orderas singing a chorus inCarousel. It turned out that Orbach wrote hundreds of short poems to his wife. Some were read at his funeral. In contrast to this loving memory was the terse funereal report filed by Carlotta Gall in theNew York Timeson November 8, 2005: "Afghan Poet Dies After Beating by Husband." Nadia Anjuman, twenty-five, who had just published a book of poems --Gule Dudi, or "Dark Flower" -- and had a second one ready for publication, had an argument with her husband. He beat her up, gave her a black eye, and knocked her unconscious; she died in the hospital. Five days later, Christina Lamb's article in theSunday Timesof London fleshed out the story. Nadia Anjuman was a woman of great courage as well as talent. In the city of Herat in western Afghanistan, she had joined a group that called itself the "Sewing Circles of Herat." Under this cover the women met, at the Golden Needle Sewing School, not to make clothes but to study literature and poetry in defiance of the Taliban's edicts forbidding women from studying. (The Taliban also forbade women to laugh out loud.) The women of the "Sewing Circles" risked grave penalties, imprisonment or worse, if caught. Nadja Anjuman survived these underground heroics but not, apparently, the wrath of a family that regarded as shameful the publication of a woman's poems about love and beauty. Brutally murdered, she left behind a six-month-old child and poems that continue to be read. "My wings are closed and I cannot fly," she laments in one ghazal, which concludes, "I am an Afghan woman, and must wail."

Was this tragic sequence of events a parable about the continuing plight of Afghani women four years after the defeat of the Taliban? An allegory in which the wielders of the pen suffer devastating losses before triumphing over the wielders of the sword? It may have been neither of these or other things that spring to mind. Yet I couldn't help translating the story into one in which poetry, emblem of free expression that it is, may be threatened with violent reprisal ending in death. Poetry, even the poetry of humor and delight, is an agent of the imagination pressing back, in Wallace Stevens's phrase, against the pressure of reality.

Copyright © 2006 by David Lehman

Excerpted from The Best American Poetry 2006

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.