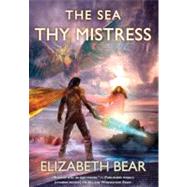

ELIZABETH BEAR is a two-time Hugo Award winning writer. She is the author of fourteen previous novels, including the first two books of The Edda of Burdens: All the Windwracked Stars and By the Mountain Bound. She lives in Connecticut.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

34 A.R. (After Rekindling)

On the First Day of Spring

An old man with radiation scars surrounding the chromed half of his face limped down a salt-grass-covered dune. Metal armatures creaked under his clothing as he thumped across dry sand to wet, scuffing through the black and white line of the high-tide boundary, where the sharp albedo of cast-up teeth tangled in film-shiny ribbons of kelp. About his feet, small combers glittered in the light of a gibbous moon. Above, the sky was deepest indigo; the stars were breathtakingly bright.

The old man, whose name was Aethelred, fetched up against a large piece of sea wrack, perhaps the wooden keel of some long-ago ship, and made a little ceremony of seating himself. He relied heavily on his staff until his bad leg was settled, and then he sighed in relief and leaned back, stretching and spreading his robes around him.

He stared over the ocean in silence until the moon was halfway down the sky. Then he reached out his staff and tapped at the oscillating edge of the water as if rapping on a door.

He seemed to think about his words very hard. “What I came to say was, I was mad at you at the time, for Cahey’s sake … but I had some time to think about it after you changed, and he … changed, you know. And I’ve got to say, I think now that was a real … a real grown-up thing you did back there. A real grown-up thing.

“So. I know it isn’t what you hold with, but we’re building you a church. Not because you need it, but because other folks will.”

A breaker slightly larger than the others curled up at his feet, tapping the toes of his boots like a playful kitten.

“I know,” he said, “but somebody had to write it down. The generation after me, and the one after that … You know, Muire. It was you wrote it down the last time.”

He frowned at his hands, remembering reading her words, her own self-effacement from the history she’d created. He fell silent for a moment, alone with the waves that came and went and went and came and seemed to take no notice of him. “I guess you know about writing things down.”

He sighed, resettled himself on his improvised driftwood bench. He took a big breath of clean salt air and let it out again with a whistle.

“See, there’s kids who don’t remember how it was before, how it was when the whole world was dying. People forget so quick. But it’s not like the old knowledge is gone. The library is still there. The machines will still work. It’s all just been misplaced for a time. And I thought, folks are scattering, and the right things would get forgotten and the wrong things might get remembered, and you know how it is. So I wanted folks to know what you did. I hope you can forgive me.”

He listened, and heard no answer—or maybe he could have imagined one, but it was anyone’s guess if it was a chuckle or just the rattle of water among stones.

“So I got with this moreau—they’re not so bad, I guess: they helped keep order when things got weird after you … got translated, and if they’ve got some odd habits, well, so do I. His name is Borje; he says you kissed him in a stairwell once—you remember that?”

The waves rolled up the shore: the tide neither rose nor fell.

“Anyway, he’s not much of a conversationalist. But he cares a lot about taking care of people. After you … left … nobody really had any idea what they should be doing. With the Technomancer dead and the crops growing again, some people tried to take advantage. The moreaux handled that, but Borje and I, we thought we should write down about the Desolation, so people would remember for next time.” He shrugged. “People being what people are, it probably won’t make any difference. But there you go.”

The moon was setting over the ocean.

When Aethelred spoke again, there was a softer tone in his voice. “And we wrote about you, because we thought people should know what you gave up for them. That it might make a difference in the way they thought, if they knew somebody cared that much about them. And that’s why we’re building a church, because folks need a place to go. Even though I know you wouldn’t like it. Sorry about that part. It won’t be anything fancy, though; I promise. More like a library or something.”

He struggled to his feet, leaning heavily on the staff to do it. He stepped away, and the ocean seemed to take no notice, and then he stopped and looked back over his shoulder at the scalloped water.

A long silence followed. The waves hissed against the sand. The night was broken by a wailing cry.

The old man jerked upright. His head swiveled from side to side as he shuffled a few hurried steps. The sound came again, keen and thoughtless as the cry of a gull, and this time he managed to locate the source: a dark huddle cast up on the moonlit beach, not too far away. Something glittered in the sand beside it.

Leaning on his staff, he made haste toward it, stumping along at a good clip with his staff.

It was a tangle of seaweed. It was hard to tell in the darkness, but he thought the tangle was moving slightly.

He could move fast enough, despite the limp, but when he bent down he was painfully stiff, leveraging himself with his staff. The weight of his reconstructed body made him ponderous, and were he careless his touch could be anything but delicate. Ever-so-cautiously, he dug through the bundle with his other hand. His fingers fastened on something damp and cool and resilient.

It kicked.

Faster now, he shoved the seaweed aside. A moment, and he had it: wet skin, flailing limbs, lips stretched open in a cry of outrage. He slid his meaty hand under the tiny newborn infant, scooping it up still wrapped in its swaddling of kelp. After leaning the staff in the crook of his other elbow, he slipped a massive pinkie finger into its gaping mouth with an expertise that would have surprised no one who knew him. The ergonomics of the situation meant both his hands were engaged, which for the time being meant as well that both he and the infant were trapped where they stood on the sand.

“Well, this is a fine predicament, young man,” Aethelred muttered.

At last, the slackening of suction on his finger told him the baby slept. Aethelred balanced the child on one hand, laid his staff down, and picked up the sheathed, brass-hilted sword that rested nearby in the sand.

“Heh,” he said. “I recognize that.” He shoved the blade through the tapestry rope that bound his waist.

With the help of his reclaimed staff, the old man straightened. Sand and seaweed clung to the hem of his robes.

The baby blinked at the old man with wide, wondering eyes, eyes that filled with light like the glints shot through the indigo ocean, the indigo night. The old man had a premonition that this child’s eyes would not fade to any mundane color as he grew.

“Oh, Muire.” Aethelred held the infant close to his chest, protectively. She’d been the least and the last remaining of her divine sisterhood, and she had sacrificed everything she was or could have become to buy his world a second chance at life. And now this: a child. Her child, it must be. Hers, and Cathoair’s. “Takes you folks longer than us, I suppose.”

He turned his face aside so that the tears would not fall on the baby.Salty,he thought, inanely. He shook his eyes dry and looked out at the sea.

“Did you have to give this up, too? Oh, Muire, I’m so sorry.”

Copyright © 2011 by Elizabeth Bear