Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

David Drake (born 1945) sold his first story (a fantasy) at age 20. His undergraduate majors at the University of Iowa were history (with honors) and Latin (BA, 1967). He uses his training in both subjects extensively in his fiction.

David entered Duke Law School in 1967 and graduated five years later (JD, 1972). The delay was caused by his being drafted into the US Army. He served in 1970 as an enlisted interrogator with the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, the Blackhorse, in Viet Nam and Cambodia. He has used his legal and particularly his military experiences extensively in his fiction also.

David practiced law for eight years; drove a city bus for one year; and has been a full-time freelance writer since 1981. He reads and travels extensively.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

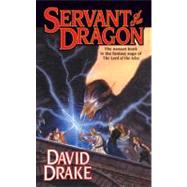

Excerpted from Servant of the Dragon by David Drake

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.