Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

| Prologue: Saginaw, Michigan, 1952 | p. 1 |

| Lula | |

| Paradise | p. 9 |

| The Sweet By-and-By | p. 23 |

| Into the Cold | p. 31 |

| Blood on the Snow | p. 53 |

| Stevie | |

| Sounds | p. 91 |

| Drummer Boy | p. 101 |

| Saint, Sinner | p. 125 |

| Signatures | p. 137 |

| Little Stevie Wonder | p. 163 |

| Showtime | p. 173 |

| Uptight | p. 189 |

| Panic in Detroit | p. 209 |

| Living for the City | p. 225 |

| Higher Ground | p. 247 |

| Epilogue: Los Angeles, California, 2002 | p. 259 |

| Table of Contents provided by Syndetics. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Saginaw, Michigan, 1952

You need a miracle. God bless you and your baby boy, but there is nothing we can do. I am so sorry.

It was the last doctor - the best doctor, the Mayo Clinic doctor - who said that. She had waited in his private office, the wriggling two-year-old in her lap, with all those impressive-looking diplomas on the wall, and then he had come in to talk to her. He was tall and intense, wearing a long, starched, white lab coat, a pair of half-moon spectacles teetering on the end of his nose. He had peered down through those spectacles at the clipboard in his hands for a great long while, and then he took the spectacles off and looked at her and the uncomprehending boy, and told her. Straight and honest. You need a miracle. God bless you and your baby boy, but there is nothing we can do. I am so sorry.

You need a miracle. Lula had taken those words home with her to Saginaw, which wasn't home at all. Not for an Alabama girl raised on a sharecropper's farm in the hot and humid middle of nowhere in the Black Belt, near a tattered little village called Hurtsboro, about a day's mule wagon ride from Montgomery in those days. That was home to her. But that was such a long time ago, eleven years now since her life crumbled around her and she made her way to this godforsaken place.

But not so long ago that she couldn't remember how it felt, then, to be back there. In times like these, with the winter cold starting to settle in, another whip-cold Michigan winter with the chill wafting into her bones like a ghost, Lula would remember what it was like back then in Alabama, where it never seemed to get cold and where children grew up strong and healthy and could see forever.

It never occurred to her, back then, that she would live anywhere else. Because when you are a child, Lula had decided, even a poor child, you don't ever really think that your world will change. You can't even picture it. You don't even know that any other world is out there. Even when times are hard and there isn't enough to eat and your back hurts so bad from picking cotton that you wonder if you'll ever stand upright again, a child will tell herself that everything is okay, because she doesn't know any better.

A little girl like that back in old Alabama...it would never enter her mind that one day she would be waiting on a platform at the train station in Columbus, Georgia, just across the state line from Eufaula, barely eleven years old, her planet in pieces, with no one to care for her but some man who called himself her daddy, a man who lived somewhere up in the grim reaches of Indiana at the distant end of the tracks. She couldn't have predicted that long, swaying, clacking train ride north and the very different world that awaited her there, gray and snowy and hardscrabble and without love. She couldn't have foretold the cruelties she would endure at the hands of ice-hearted men reeking of whiskey, men who would spend their money and their nights next to a warm stove in a gambling house rather than buy coal for their women and children shivering in a drafty, freezing stand of sticks back home. Those cold nights! Those nights when you sit there wrapped in some threadbare blanket and flimsy shawl, fighting off the ghost chill, thinking about that breadwinner who might come with money or who might not, but will sure enough come home sooner or later with anger in his soul.

That little girl chasing her favorite cat down a dusty dirt road near dark couldn't imagine any of that. Not when the sun is almost gone and the air is like a wondrous warm liquid and the crickets begin to rumble and the fireflies are darting and fluttering, their tiny yellow lamps flickering as if there is nothing amazing or spectacular about it at all. And there isn't, not when you're a little girl and you believe the world is a place where things are good and constant and make sense. You could never see yourself in a bitter-cold, crazy-dark tenement hallway with the knife in your hand, your jaw throbbing from the balled fist, a flash of blade and blood, the howling, the crimson tracks across the dirty, moonlit snow.

No, that little girl couldn't see any of that, not on a hot, savage-bright Sunday morning alongside a red-clay dirt road, with the church windows flung open to catch even the promise of salvation or a breeze, handheld paper funeral-home fans foaming back and forth like whitecaps on a choppy sea, the sound of the choir filling up the little white building as if it would burst. Not when the preacher, looming like an apparition, is up there bellowing and frothing at Satan in a voice that surely reached into the bowels of Hell, a voice strong and pure enough to make Satan think twice before attempting to deliver his evil into the hearts of this solid-rock congregation. A little girl wrapped in that much love and faith couldn't possibly envision a life where the Devil runs unchecked, where wind and hearts and blood run cold.

That young girl couldn't peer into the future and see that baby, her third child, born too soon, destined to spend fifty-two days in an incubator. She couldn't envision the day when that precious baby boy, the one with a special spark even as a tiny thing, the special spark that stopped people on the street - Look at that child! - she couldn't foretell the day when that doctor would take off his half-moon spectacles and tell her, straight and honest: You need a miracle. There is nothing we can do. I am so sorry. Or how people would stop her in the street; Look at that child! they would say. That child has the spark, the spark of something I've never seen! A little girl couldn't see that, not when she dreams of her own grown-up life, of some fine husband and their fine children and their life together, a life full of warm-liquid evenings and rumbling crickets and fluttering lightning bugs and churches and choirs and bellowing sermons and Sunday fried chicken and white tablecloths, a life of being wrapped in a man's love, in God's love.

The doctor's words stayed with her: You need a miracle. Little Stevie's affliction would have to be in the hands of the Lord now. But what kind of God would take from a helpless child the power of sight? Lula had seen them on the streets, the blind beggars and panhandlers, selling their pencils and gum and asking for handouts, dirty and pathetic and lost. In night terrors she saw Stevie huddled on the pavement, his mother dead and gone, and the panic would well up within her again, panic and desperation, the desperation that builds in a mother's heart when she has given up on the doctors and the hospitals and the clinics, and wonders what else she can do.

And then, on the radio: hope.

The radio preacher, the one who heals the sick and lame and - Yes, Lord - the blind, the one who exhorts demons from sinners, makes the drunks put their bottles down, brings the unconscious and near-dead to life, that preacher is telling his listeners about an upcoming trip to the Midwest. St. Louis and Topeka and Kansas City and Gary and Detroit and Saginaw and...Saginaw! At the fairgrounds. The hope rises in her heart, and she prays her thanks to God, and she mails in an offering of three hard-won dollars. The name of the preacher's radio program is Healing Waters. The lame and the halt and the blind have been restored by this man of God, and if God wills it, her little boy might see.

And so weeks later she wrapped the boy, walking good now, in his warmest clothes and begged a ride to the fairgrounds pressed hard against the outskirts of that cold and forbidding town, where the big revival tent loomed like the Promised Land bathed in torchlight. Admission is free, dear Sister, just remember the Lord when the plate is passed. It was warm inside, hundreds of people already there, black and white, clapping in time to the gospel singers onstage. Little Stevie was perched on her hip, mesmerized.

Shortly the singing stopped and the Reverend Oral Roberts took the stage, throwing a bolt of electricity through the still-growing, jostling crowd. The preacher, his stallion-black mane of hair glistening, started slow and quiet and stealthy and then began to pummel the crowd with his piercing taunts of their unworthiness before God, taunts punctuated by amens and dramatic chords from the piano. Finally, he sent out the call: "Who among ye would be healed? Who among ye would be healed before God?"

Dozens surged toward the stage. Lula gripped the boy tightly and began to force her way to the front, like a determined fullback swimming for the goal line. At the foot of the stage, amid the swirling tumult, men in suits were choosing who would be allowed onstage and turning others away; Lula still was at least fifteen feet away when one of the men began to bark, No more! No more! She bulled closer and somehow hoisted Stevie in the air. My baby is blind! she yelled. My baby is blind! A thickset white man beside her took up the chant: Her baby is blind! Her baby is blind! And suddenly the crowd just seemed to part, and she was there, the boy bawling, the men hustling her up onto the stage.

It seemed like something out of the New Testament, the braying multitude, the cursed and the afflicted before them, an old crippled man next to Lula speaking in tongues. Another elderly man in front of her shook uncontrollably, his body racked by palsy. Behind her, a young woman's face was marred by a spidery lesion. And Stevie, his opaque eyes rolling back into his head, but not crying now, instead quiet, rigid, instinctively transfixed by the moment. One by one, the preacher began to minister to them, laying his hands on tormented bodies, beseeching God to heal them, to stop the Devil's work, to allow this gentleman to walk unaided, to stop this elderly brother's tremors, to restore beauty to this young woman's face. One by one, he challenged God to invoke His mercy. And, one by one, the afflicted responded. The blathering old man fell silent, reason suddenly reflected in his face, and then he abruptly let his crutches fall away, standing gingerly yet unaided. "Praise God!" someone shouted, and the crowd cheered. The palsied gentleman ceased shaking; the crowd thundered. Roberts placed his hands on the young woman's face, then swept them away; the blight was gone. She gaped in astonishment as someone held a mirror before her. The stage fairly shook with the crowd's seismic roar of approval.

Stevie and Lula were last.

That little girl in long-ago-and-faraway Alabama could never have imagined a time when she would crumple to her knees before a crowd on fire, clutching her precious child as if he might suddenly ascend to heaven on wings, tears of terror and joy plummeting down her face, the radio preacher placing his hands over the boy's eyes and yelling time and again, "I command you to see! In the name of Almighty God, I command you to see!" and the doctor's words echoing in her head, in her heart, and on her lips:

You need a miracle!

You need a miracle!

You need a miracle!

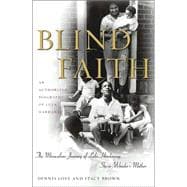

Excerpted from Blind Faith by Dennis Love and Stacy Brown Copyright © 2002 by Dennis Love, Stacy Brown, and Lula Hardaway

Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.