Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

| Editor's Foreword | vii | ||||

| Note on the Text | xv | ||||

| Acknowledgments | xvii | ||||

| Prologue | xxi | ||||

|

1 | (3) | |||

|

4 | (5) | |||

|

9 | (5) | |||

|

14 | (12) | |||

|

26 | (7) | |||

|

33 | (7) | |||

|

40 | (8) | |||

|

48 | (5) | |||

|

53 | (14) | |||

|

67 | (10) | |||

|

77 | (4) | |||

|

81 | (9) | |||

|

90 | (21) | |||

|

111 | (25) | |||

|

136 | (8) | |||

|

144 | (11) | |||

|

155 | (6) | |||

|

161 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

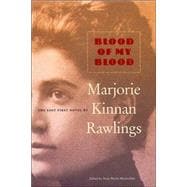

Blood of My Blood

As a girl of sixteen, Ida Traphagen stood before a walnut-framed mirror in the paternal farmhouse in Michigan and cried bitterly because she was so homely. The tears did not increase her charms. Her face was sharp and angular, with a pointed chin, high cheek-bones, slightly protruding upper teeth, an indeterminately formed mouth of some width, and a long, crooked nose. Her eyes, of a nice blue, were small. When she cried, the lids reddened and swelled almost shut; the nose became red and swollen at the tip; the upper lip swelled entirely out of shape. The spectacle, reflected in the mirror, brought fresh tears, ending with a violent nervous headache to which all her life she was subject.

After the tempest had subsided, leaving only the headache and a profound, resigned melancholy, she would go out to the windmill and pump fresh icy well-water with which to bathe her throbbing eyes and head. The farmhouse was equipped with running water through a homemade piping system, but by the time the water had passed through the pipes in the warm kitchen, its coldness was somewhat expended. She also hoped, by going outside, to avoid her mother; to heal her wounds, as it were, before the pretty, plump, sharp-tongued and stupid little woman could rub salt into them. It took so long for the redness and swelling to subside, however, that Fanny usually came upon her, or called her, before she had recovered from her lachrymose debauch.

"My Lord, Idy, you've been cryin' again. You're the homeliest thing I ever laid eyes on. It doesn't help that long nose of yours to get it red as a beet, and my land, look at your eyes."

The girl looked appealingly at her mother, mute with spent suffering. She had said these things to herself, over and over. The repeated words fell like blows on a heart already numb with pain. She felt them strike and bruise, but she was past bleeding under them.

Her mother's purpose was honest, even laudable. She only wished to point out to her daughter that it was a mistake to make herself more unattractive than was necessary, by indulging in tears. Incapable of delicacy, she relied on the maxim, "Tell the truth and shame the devil." She used the rapier of her tongue without a foil, and not content to make a thrust and cry "Touché!", must make sure that its point sunk deep within the vulnerable flesh.

What would have been the effect on her life, even on her granddaughter's, if Fanny Traphagen had been able to lave her child's aching forehead and sensibilities? She knew why Ida cried. She might have said:

"You are young and healthy, with a fresh, lovely complexion. You have soft, beautiful, chestnut-brown hair. There have been women in history who have gone far, with longer, crookeder noses and higher cheekbones than yours. George Sand was ugly, but she was famous and sufficiently beloved. Your physical appearance is a matter of no import."

But, what would you? She knew nothing of famous women. She had neither read nor heard of them, being glad to read and write a very little, and to hear as history the old wives' tales of her own locality, which had to do with births and deaths and scandals.

She might have said:

"If you acquire wisdom, my child, its white light will transform your plain features. If you acquire beauty of spirit, other souls, attuned to yours, will fly like birds to you and call you lovely."

Not knowing these things, she said:

"I don't know what man will ever want you. It's bad enough for you to look like your poor homely Pa, without taking after his solemn disposition."

The pebble drops in the source water of the shallow stream. Its course is deflected. It goes down this valley instead of that; it meets streams from these mountains instead of those; in a now unavoidable compulsion, the creek must eat its way through sand and thorny areas and never know the rich verdure a few miles away. A certain sort of river, composed of certain elements, arriving by a certain route, flows at last into the eternity of the sea. It is all one to the sea, but who can say that it is a matter of indifference to the river?

Chapter Two

Fanny and Abram

There are minds, like soils, incapable of fertility. No amount of enrichment, of cultivation, can produce in them any crop but weeds. Fanny Osmun Traphagen had one of these. Nothing existed for her except the surfaces skimmed by her eyes, blue as cornflowers. Nothing penetrated her head, framed in curls as soft, as golden-brown, as the heart of a chestnut burr, except the casual facts of life and its far from casual conventions. The middle-class virtues flourished in her, their natural milieu, and she passed them on to her children like stern and sacred vessels.

She taught them cleanliness. Ida, her first-born, received the full effect of her mother's horror of the sacrilege of dirt. A house, regardless of circumstances, must be "gone over" every day. It must be "cleaned" once a week, in every crack or crevice, visible or invisible. "Spring cleaning" and "Fall cleaning" were grim gods, on whose bloody altars were sacrificed biannually the peace and comfort of the family and entire nervous equipment of the housekeeper.

She taught them honesty, morality; then threw these desirable qualities into utter confusion by giving them at the same time a wide-eyed reverence for wealth and the material aspects of success, no matter how achieved. Long years later, her daughter Ida was to astonish her own daughter by denying her ethical gods when they came in conflict with her material ones.

Fanny Osmun married Abram Traphagen because he embodied these very ideals. He was clean, honest, and moral, and by the standards of the still pioneer, Michigan community, he was on the way to agricultural success. At sixteen, he had inherited one hundred and sixty acres of partly cleared land from his father. At nineteen he had completed a decent frame house and a red barn, and Fanny, her character as fixed at seventeen as it was to be at seventy, decided that he was the best she could do and married him. She moved into the new house with smug satisfaction; rearranged the few pieces of furniture, made a mental note of what she must soon have in the way of an organ, a plush settee, and a chromo portrait of herself; clamored for a larger vegetable garden past the little white gate in the side yard; planted her own woman's garden of bleeding heart, salvia, cosmos, four-o'clocks, rose geranium and sweet lavender; and began the long business of giving birth to Abram's seven sons and daughters.

Abram adored her. She heckled him, nagged him, lashed him with her flickering little tongue, condescended to play cruel practical jokes on him, such as hiding in the wood on the dark road up which he would come and springing out at his horses with an inhuman shriek, startling them into runaways that gave him once a broken collar-bone. Her perverted humor delighted him. He coaxed her as a middle-aged woman to let down her gold-brown curls and tie them with a red ribbon and bring his lunch to him in the field. Her petite plumpness became plumper, the chestnut curls became soft silver, but she was a pretty woman up to the final day, when the saliva drooled over her chin and the blue eyes glazed at last. Even her children and grandchildren, when most annoyed by her blindness, her prejudices, her mental sterility, loved to look at her.

No one loved to look at Abram, except those who saw his six feet three of weather-beaten gauntness as being beautiful as a gnarled oak deep-rooted in the soil he loved. His shoulders were from boyhood a little stooped with bending over furrows and young plants. His eyes were always a bit a-squint from looking at the sky for weather portents. His step was slow from much weariness, and because one cannot hurry the seasons, or the rain, or the dawn. He walked with the deliberate gait of a very thin elephant and stared ahead of him with the same preoccupation. His solemnity and high cheekbones had about them something of the Indian, with whose Fisher tribe he had much consorted as a lad.

"Abe's half Indian, talks their lingo," his father used to say.

And one of Ida's earliest memories was of an old brave who brought them fish and venison as thanks for trapping on their lakes and streams. She would come down the back stairs in the early morning and find him sleeping in the kitchen, rolled up in his blanket. Abram's grandfather had doctored their horses and repaired their implements, and about the Triphauven family, until the Fishers disappeared, there was a girdle of their wild affection.

Abram did all his work with, to a quicker man, a maddening slowness. He came in from his evening chores almost an hour behind his neighbors; but his chores were better done; the cows milked dry; the plow-horses groomed and their harness sores attended to; their straw bedding was thicker; the hired man was driven to the keeping of cleaner barns and stables.

He ate with inconceivable deliberation, chewing each mouthful of food with the slow gravity of a horse. His great bony jaw swung back and forth, back and forth, and creaked on its hinges. His Adam's apple surged up and down like a slow piston. His hand was knotted and immense. There was a spread of twelve inches between thumb and forefinger, stretched apart, he said, by swinging the axe for weeks on end. When he wrapped his crooked brown fingers around his table knife, or picked up a fragment of meat with them, his hand covered his plate. His joints creaked. When he sat down, his bony knees threatened to cut holes in his

(Continues...)

Excerpted from Blood of My Blood by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings. Copyright © 2002 by University of Florida Foundation. Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.