| Introduction | xiii | ||||

| Author's Note | xxi | ||||

|

1 | (34) | |||

|

3 | (11) | |||

|

14 | (8) | |||

|

22 | (13) | |||

|

35 | (42) | |||

|

37 | (23) | |||

|

60 | (17) | |||

|

77 | (52) | |||

|

79 | (17) | |||

|

96 | (11) | |||

|

107 | (22) | |||

|

129 | (60) | |||

|

131 | (21) | |||

|

152 | (37) | |||

|

189 | (58) | |||

|

191 | (11) | |||

|

202 | (25) | |||

|

227 | (20) | |||

|

247 | (30) | |||

|

249 | (14) | |||

|

263 | (14) | |||

| Afterword | 277 | (8) | |||

| Acknowledgments | 285 | (4) | |||

| Appendices | 289 | (12) | |||

| Notes | 301 | (12) | |||

| Photo Credits | 313 | (2) | |||

| Index | 315 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

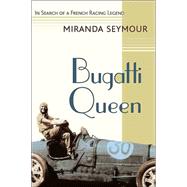

Excerpted from The Bugatti Queen: In Search of a French Racing Legend by Miranda Seymour

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.