| Acknowledgments | p. ix |

| Foreword | p. xi |

| Genealogy of the Labauve Family from 1815 | p. xiv |

| Meet the Labauve Family | p. xvii |

| Glossary | p. xxi |

| Cajun Cookery: A Love Affair with Food | p. 1 |

| Gumbo and Soup: Great-Grandma Marie Clara: Life on a Cajun Farm and the Beginning of Home Place | p. 23 |

| Poultry: The Great-Great Uncles: Murder, Music, and Mallards | p. 55 |

| Meat: Grandma Olympe and Her Magic Bag | p. 81 |

| Seafood: Grandpa Pischoff Sneaks into the Kitchen | p. 109 |

| Sweet and Savory Bakery: The Great-Aunts: The Vanilla Lady and the Lonely Trousseau | p. 135 |

| Vegetables and Beans: Great-Uncle Adolphe: The Country Store on the Farm | p. 161 |

| Salads, Salad Dressings, and Sauces: Dad and the House Under the Redwoods: Cajun in California | p. 187 |

| Dressings, Potatoes, and Grits: At Aunt Lorna's Table | p. 217 |

| Desserts: Our Cajun Kitchen Today | p. 241 |

| Sources | p. 267 |

| Bibliography | p. 269 |

| Index | p. 271 |

| Table of Contents provided by Ingram. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

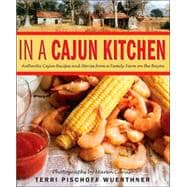

Excerpted from In a Cajun Kitchen: Authentic Cajun Recipes and Stories from a Family Farm on the Bayou by Terri Pischoff Wuerthner

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.