What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

SEPTEMBER 11

On the morning of September 11, 2001, Michael Wright, a 30-year-old sales executive, woke at 6:30. Stocky, with a broad Irish face and an easy manner, he rolled over to hug his wife, then remembered she'd gone with their four-month-old son to visit Michael's parents in Boston. With the place to himself, Wright thought about sleeping in, but heard his grandfather's voice barking at him from the grave: "Get your lazy butt to work."

Outside his apartment-a brownstone floor-through facing Prospect Park in Brooklyn-it was a brilliant end-of-summer day, bell-clear with a hint of coolness in the air. Wright was looking forward to work. He had two deals pending and with plans to buy his apartment, he was eager for the commissions. Showered and dressed, he made the subway commute into Lower Manhattan in 20 minutes and exited on Broadway and Dey Street, two blocks due east of his office, a telecommunications equipment company headquartered in the World Trade Center.

Looking up, he marveled at the familiar Twin Towers massed against the sky. Sunlight glanced off the steel rails running up the buildings' sides, making them shine. But what really impressed Wright was their size, their head-snapping height, the sheer, unholy dimensions of their heavenly reach. They embodied, as no other buildings did, the economic muscle he wanted his company to project each time he handed out his business card or told someone where he worked. He walked briskly across the plaza and took the elevator to the 81st floor of the North Tower, getting to his desk by 7:45.

While Wright got started on paperwork, Mayor Rudy Giuliani was bullying midtown traffic in his official car, a white SUV familiarly known as the ice-cream van. He was headed for a breakfast meeting at the Peninsula Hotel on West 55th Street with his counsel, Dennison Young, then back uptown to the Richard R. Green School in Harlem to vote in the elections that would determine his successor. It was Primary Day in New York and the city's political nerves were twitching.

As Giuliani entered the Peninsula's starched dining room shortly after 8:00 A.M., American Airlines Flight 11 was making its ascent over Boston's Logan Airport. En route to Los Angeles, the wide-bodied jet carried 81 passengers and a crew of 11. About 10 minutes later, a second Boeing 767 took off for LA. This flight, United Airlines 175, carried 56 passengers and a crew of nine. Both flights departed without incident, and control tower workers were settling into their early-morning routines when at 8:14, the American plane failed to respond to an air-traffic controller's instruction to increase its altitude. The controller tried to raise the pilot on the radio, without success. Then at 8:28, he overheard a strange communication originating from the plane's cockpit. "We have some planes," an accented male voice announced. "Just stay quiet and you will be okay. We are returning to the airport. Nobody move. Everything will be okay. If you try to make any moves, you'll endanger yourself and the airplane. Just stay quiet."

Moments before, an American Airlines reservations supervisor had received a call from Betty Ong, a flight attendant on Flight 11, describing a hijacking in progress. The supervisor had patched the call through to Craig Marquis, the veteran manager-on-duty at American's operations center in Fort Worth, Texas. Nearly hysterical, Ong told him that two flight attendants had been stabbed and that one was dead and one was on oxygen. The hijackers, she said, had also slit one passenger's throat and stormed the cockpit.

While Marquis verified Ong's employee number and gleaned details about the hijackers' seat assignments, air-traffic controllers tried to track the hijacked plane's flight path. It had turned south over Albany in the direction of New York City and begun flying erratically-apparently while the hijackers were overcoming the pilots-but the hijackers had then turned off the flight transponder, a device that allows controllers to distinguish a plane's radar image from among the hundreds of other blips on a screen. The controllers had no idea where the plane was heading.

As the controllers made last-ditch efforts to communicate with AAL 11, Mary Amy Sweeney, a 35-year-old attendant on the flight, called Michael Woodward, an American flight services manager at Logan, and went on to calmly describe the hijackers as four Middle Eastern men, some wearing red bandanas and wielding box cutters. "This plane," she said, "has been hijacked."

Suddenly, she reported, the plane swerved and began descending. "What's your location?" Woodward asked her. Sweeney looked out a window and told him she saw water and buildings.

"Oh my God," she said then. "Oh my God."

About 8:45 Michael Wright visited the men's room, located near the elevator bank at the center of the 81st floor of the North Tower. On his way out he ran into a coworker, Arturo Gonzalez, and stopped briefly to chat with him. Suddenly the building shuddered and Wright heard a crash-a screeching, metal-on-metal jolt-and was thrown back against the wall.

The lights blinked and for a moment, the whole building seemed to teeter. Wright waited for the room to settle and adjusted his vision. Everything had changed. The marble facade on the opposite wall was shattered and a huge crack had opened up in the drywall behind. The floor had buckled and Gonzalez was propped up against the broken vanity. The sinks themselves had moved out from the wall. "What the fuck was that?" Wright asked.

"Holy shit," Gonzalez intoned.

Smoke threaded through the air between them.

They headed out to the hallway, where the devastation was horrendous. Chunks of roof were falling, the facing wall was ripped open and the elevator doors to their right had blown out. The whole building, Wright realized, had shifted on its foundation. Every joining surface was awry; every hinge was twisted or bent. A crater had opened in the floor ahead of him exposing wires, pipes, girders and beams at least ten floors below. Acrid smoke poured out of the elevator shafts.

Wright's instinct was to get the hell out of there, but instead he turned back toward his office to check on his coworkers. As he ran past the elevators, he heard screaming from the ladies' room. The jamb above the door had caved, trapping whoever was inside. Gonzalez and another colleague began kicking down the door.

Wright's 30 or so officemates were pouring out into the hall. Some were calm, others terrified or in tears. He directed them to the stairwell. Flaming chunks of material were falling around them and Wright could smell burning fuel, though he had no idea where it was coming from.

John O'Neill, the World Trade Center's 49-year-old chief of security, dashed out of his South Tower office to assess the situation. A brusque, larger-than-life New York character, O'Neill had spent all but a few days of his professional life at the FBI, the last eight years as one of its top counterterrorism officials. Ironically, he'd retired from the Bureau two weeks before in order to take what friends called a cushy private-sector job, and former colleagues still regarded him as the nation's most knowledgeable counterterrorist. Only the night before, over dinner with friends, he'd expressed a fear that New York was ripe for an attack like the one he now found himself in the midst of. He made a quick damage inspection, placed a call on his cell phone, and then sprinted back inside to help coordinate the rescue effort.

Joe Lhota, Rudy Giuliani's chief of staff, felt the explosion in his office at City Hall almost a half mile from the World Trade Center. He dashed out onto the steps, saw the flames engulfing the tower and called Giuliani at the Peninsula. An aide answered the phone. "Tell the mayor a plane has hit the Trade Center," Lhota said.

Back downtown at One Police Plaza, anxious aides; pounded on Bernie Kerik's bathroom door. The 46-year-old bullet-shaped police commissioner had worked out earlier in the vest-pocket gym attached to his office and was taking advantage of a break in his busy schedule to shower and change. He answered the door wearing nothing but a towel, a beardful of shaving cream, and a "this better be good" expression.

"A plane just hit the World Trade towers," several staffers said at once.

"All right, relax. Calm down," Kerik said, noting the worry in their faces. He was thinking small aircraft, an accident.

"You don't understand, Boss," John Picciano, his chief aide, said. "You can see it from the window. It's enormous."

Kerik realized that every phone on the floor was ringing.

Still wrapped in a towel, he followed Picciano through the outer office to a conference room at the southwest corner of the building and looked out at the Trade Center. Then he ran back to his office to call the mayor, who was already headed downtown, and got dressed.

He was out of the building within four minutes, at the scene in eight. Pulling up in his black four-door Chrysler at the corner of Vesey and West Broadway, he saw people jumping out of windows 90, 100 stories up, one after another. For the first time in his 25-year law enforcement career, he felt totally helpless.

More than a thousand miles away, at American's operations center in Fort Worth, top executives were experiencing similar feelings. With the assistance of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the center's technicians had finally managed to isolate Flight 11's radar image on Aircraft Situation Display-a big-screen tracking device used for just such emergencies-and stunned officials watched as the blips approached New York, froze and then vanished. Still no one knew what had happened. Even when a ramp supervisor called from Kennedy Airport several minutes later to report that a plane had crashed into the World Trade Center, they couldn't believe that it was Flight 11.

Meanwhile, air-traffic controllers back east were scrambling to make contact with two more rogue planes. Even before the first World Trade Center crash at 8:41, United's Flight 175 seemed to be in trouble. One of the pilots had radioed that he'd heard a suspicious transmission emanating from the cabin shortly after takeoff. "Someone keyed the [cabin] mike and said, `Everyone stay in their seats,'" the pilot told the controllers. Minutes later, the plane swerved off course and shut down communication.

Almost simultaneously, air-traffic controllers lost contact with a second American flight, AAL 77, a Boeing 757 en route from Washington's Dulles International Airport to Los Angeles with 58 passengers and 6 crew on board. At 8:56, just moments after the first World Trade Center crash, that plane doubled back toward Washington, shut off its transponder, and didn't answer repeated calls from a controller out of Indianapolis.

Airline executives were finding it impossible to keep abreast of developments in the air. Officials at United's operations center outside Chicago had just gotten news of the first Trade Center crash, when Doc Miles, the center's shift manager, received an alarming communication from United's maintenance department in San Francisco. Moments before, a mechanic had fielded a call from an attendant on Flight 175 saying the pilots had been killed, a flight attendant stabbed and the plane hijacked.

Miles questioned the report; it was an American Airlines jet that had been hijacked, he pointed out, not a United plane. But the mechanic confirmed that the call had come from United Flight 175 from Boston to LA and frantic efforts by a dispatcher to raise the cockpit were met with silence. Meanwhile, executives watching CNN on an overhead screen in United's crisis room saw a large, still unidentified aircraft crash into the Trade Center's South Tower.

I had just walked out of Good Morning America's Times Square studios and when I'd got to my car all hell had broken loose. My pager went off. My cell phone rang, and so did the car phone. I know from experience, this is never good news.

"A plane crashed into the World Trade Center," Kris Sebastian, the ABC News's national assignment manager, told me.

"I'm on my way," I said. I calculated the routes to the scene. I could get there in 12 to 15 minutes if I drove a smart, back-road route and ran some lights. But a network crew starting out from the office would take longer, and a satellite truck, which is what I would need to "go live," would take an hour to be ready for broadcast. I really wanted to go to the scene. That's what I had done my whole life. I was a "street guy." But I also realized that the news choppers would already be broadcasting live pictures from the scene.

I could hear information pouring out of the police radio in my car. When I finally got to the corner of 44th Street and Eighth Avenue, I called the news desk and told them: Change of plans. I'm coming in and will help with live coverage from the set of the ABC News Desk.

Not much more than a minute later, police radio still in hand, I was sitting down next to Peter Jennings. We watched with astonishment as the second plane crashed into the other tower. Peter, never one to rush to conclusions-especially on the air-looked at me. "Whatever we thought this was, we now know what it is," I said. "This is a terrorist attack."

* * *

Back at the site, Kerik was patrolling the plaza's uptown boundary, making calls on his cell phone and shouting instructions at chief aide John Picciano to set up a command post a few blocks north, when he heard the explosion of the second crash. He looked up and saw a massive fireball shooting out of the South Tower straight at him. But he didn't see the plane itself, which had banked low across the harbor and slammed into the south side of the building. "How the hell did the fire leap from one tower to the other?" he wondered.

There was no time to figure out what happened. The crash was sending debris flying toward Kerik and his men. For a moment they stood transfixed, watching the deadly shrapnel make its descent. It looked like confetti, it was so high. Then someone yelled at them to get out of there and they took off up West Broadway.

As Kerik ducked around the corner into a garage on Barclay Street, someone told him that a United Airlines plane had hit the building. Instantly he realized they were being attacked by terrorists. He thought, "How many more planes are up there? What are the other targets?" He began calling for a mobilization and ordered his chief deputy commissioner to evacuate police headquarters, City Hall, the UN, and the Empire State Building.

Within minutes, Giuliani arrived at the corner of Barclay and West Broadway, and Kerik, joining him, reported that the city was under attack.

Continue...

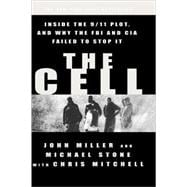

Excerpted from THE CELL by JOHN MILLER AND MICHAEL STONE, WITH CHRIS MITCHELL Copyright © 2002 by John Miller Enterprises Ltd. and Michael Stone

Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.