| Prologue: Meat Me in St. Louis | p. 1 |

| Atomic Meltdown | p. 11 |

| Attaining Outcast Status | p. 27 |

| "Dan Mathews: We Will Kill You" | p. 43 |

| Young Hustler, Ancient Rome | p. 59 |

| A Reluctant Revolutionary | p. 75 |

| All the Rage | p. 93 |

| Doofnac Xemi | p. 111 |

| This Is a Raid | p. 119 |

| An Alpine Diversion | p. 143 |

| Cinderfella | p. 161 |

| Ladies Who Lunch | p. 189 |

| Bedlam | p. 199 |

| Committed | p. 221 |

| Epilogue: Dismal Swamp Thing | p. 243 |

| Acknowledgments | p. 255 |

| Table of Contents provided by Ingram. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter 1

Atomic Meltdown

The strongest earthquake ever to hit North America struck Alaska on March 27, 1964, killing 117 people and propelling a fifty-foot seismic sea wave southward in the Pacific at 450 miles per hour. Anxious forecasters reported that the tsunami, which battered parts of the Canadian coast, might roar ashore in Southern California overnight.

After watching doomsday predictions on the late news, Ray kissed his wife, Mary Ellen, and went to bed, figuring their small suburban house, located an hour south of Los Angeles near Newport harbor, was on a hill high enough to keep the young family dry. Ray dozed off, but Mary Ellen couldn't. As the town nervously slumbered, she enlivened, feeling the familiar pull of some magnetic force inside that lured her to wherever the action was. Carefully tiptoeing into the bathroom, Mary Ellen combed up her dark blond hair, applied her trademark kissy pink lipstick, slipped out into their maroon Plymouth Belvedere station wagon, and made a beeline for the beach in hopes of beholding history. I was her unwitting accomplice; she was pregnant with me at the time. I was headed for adventure before I was born.

Mary Ellen meandered around closed sections of the Pacific Coast Highway and found a perfect spot near Newport Pier, where she was dazzled by the stars and sea and saluted by fellow disaster fans. Then, without warning, it came. Not the tidal wave, but a radio report that the surge wouldn't amount to much more than a surfable swell. With a sigh, Mary Ellen joined the other disgruntled rubberneckers at a beachfront coffee shop that had stayed open to cater the calamity. She sat alone at the counter, disappointed that Mother Nature had thwarted her late-night sightseeing excursion.

I learned from Mom that life is a parade that is more exciting to march in than just let pass you by. Her independent spirit stems from a ragamuffin childhood spent bouncing between orphanages and foster homes in Virginia and Washington, D.C., where she often skipped school to attend trials at the Supreme Court or watch Congress in action. She was at the Capitol in pigtails when FDR arrived to declare war on Japan.

My parents met in Reno, "The Biggest Little City in the World," in the late 1950s. Mary Ellen had ventured west and become a blackjack dealer at Harold's Club, an old casino with a gigantic mural of stagecoach pioneers that towered above Reno's downtown neon strip. Hired more for her looks than her gaming skills, she dealt cards in shiny cowgirl boots, form-fitting gabardine western slacks, a red-checkered shirt with silver collar tips, a bandana, and a cocked ten-gallon hat. She rented a room by the week at a motel where a handsome, friendly young man named Ray was working for the summer. Tall and trim, with closely cropped dark hair and hazel eyes, Ray had unpretentious charm. One afternoon in the parking lot, while kneeling to fix her hair in the side-view mirror of somebody's jalopy, she spied him approaching.

"Are my bangs straight?" she asked, flashing her baby blue eyes. They must have been; the two soon got married and moved to Southern California.

Ray, whose Jewish family stowed away on a Canadian-bound boat to flee persecution in the Ukraine in 1902, grew up in a rough Latino section of East Los Angeles. He's a good-humored, hardworking optimist whose passions include the Civil War, road trips, and food, all of which got passed on to me. He often takes bites from everybody else's plates, another trait I inherited. Shortly after my parents married, Dad was employed as a chicken truck driver, but eventually he landed a job managing restaurants, and they settled into a small house in Newport Beach, an upscale town in ultraconservative Orange County. Ray and Mary Ellen, who were active volunteers for John F. Kennedy's presidential campaign, never fit into the prim, atomic-era enclave, but they felt the area was ideal for raising a family. My brother Mike was born in 1963, I surfaced in '64, and Patrick arrived in '67. In keeping with American tradition, my parents divorced in '71.

Having flunked middle class, Mom, Mike, Patrick, and I moved inland to Costa Mesa, a bland suburb made up of strip malls and fast-food joints brimming with tanned white people who were really happy that the weather was nice. We lived in a succession of dingy two-bedroom apartments; Mike got his own room because he was oldest, and Patrick and I grudgingly shared the other room. Mom slept in the living room on a shabby couch surrounded by overflowing bookcases and a thrift-shop television with a wire-hanger antenna.

Although we continually slipped down rungs on the economic ladder, Mary Ellen insisted that we'd always be culturally refined, a declaration she'd make in a dredged-up Southern drawl. Every Saturday morning, as Led Zeppelin blared from a neighbor's apartment, Mom would switch on the classical station and blast opera, live from the New York Met. Then she'd apply a greasy facial and flit about the hovel scrubbing floors and windows, often in tears -- not because she hated housework but because she was moved by some emotional aria. Mike, who was always the most sensible among us, shared Mom's tuneful tastes and became a Beethoven buff, often playing his junk-shop violin or the beat-up piano crammed into a corner of the living room. My ears bled. The closest to classical I could get was the Electric Light Orchestra, whose songs I taped off the AM radio when I wasn't giggling with Patrick to a crass Cheech & Chong record. Or cheering in front of the television when my favorite skater flipped an opponent over the guardrail in the Roller Derby. If my brow were any lower, it'd be a chin.

Each evening, when Mom got home from whatever bookkeeping job her temp agency had sent her to, Mike, Patrick, or I would have the Hamburger Helper ready, and we'd eat and watch the news. Always up-to-date on local and global affairs, Mom had a sarcastic, unpredictable opinion on everything from bra burning ("What fool with boobs would do that?") to people who tie sweaters around their waist or shoulders ("They should be removed from society"). Once in a while Mary Ellen skipped work to volunteer for an urgent cause of the day, ranging from marching with downtrodden Mexican immigrants to helping Malibu millionaires dig their homes out from under mudslides. She would have nothing to do with the most notable local organization, however: the national headquarters of the extreme right-wing John Birch Society. Mom readily introduced herself as "the last of the Socialists," which didn't win her invitations to many Tupperware parties.

Most parents shield their children from the world's unrest, which, I believe, has caused an epidemic of apathy; by the time kids are deemed old enough to "understand," they've grown comfortably accustomed to not caring. Mary Ellen, in her often irrational and always emotional way, made us feel obliged to choose sides in any issue in the news. When Walter Cronkite reported that Anita Bryant was hit in the face with a pie by gays protesting her crusade against Florida's antidiscrimination bill, Mary Ellen leaped from the table and cheered, then turned down the sound to spell out the controversy to Patrick, Mike, and me.

"Gays are boys that love boys and girls that love girls," she said. "Some idiots are threatened by gays because they say the Bible dictates you should only love people in order to have kids, which happens when a boy loves a girl. That's asinine -- boys and girls love each other all the time without having babies, and anyway there are too many people in the world." My prepubescent brothers and I didn't really understand the "baby" part, but we loved the idea that somebody tossed pies, and we wanted to meet these pranksters, these gays.

"Boys," Mom continued, "I'm going to enroll you in ballet so you can be around them -- they're lots of fun." We were in tights by Christmas, having landed roles as dancing rats in a regional production ofThe Nutcracker.

Mom's political opinions were often shared with politicians, usually by telegram, despite the cost, even if it meant we bounced the rent check. President Nixon received such a telegram, demanding he withdraw troops from Cambodia, and when we didn't receive a favorable reply, an impeach nixon sign went into our front window.

"Oh, I like Nixon, too," said a simple, smiling neighbor without a trace of irony. "Merde," Mom sighed, rolling her eyes. "Well, at least she understoodoneword."

The only filthy phrase in our home was "Mind your own business." Mom instilled in us a meddling, protective vigilance, which can be traced to the institutional neglect she endured growing up in orphan asylums during the Great Depression. We learned to observe and react to the world around us, to show a sense of responsibility, and to keep an eye out for others. Even animals.

One afternoon during third grade I was walking home from school and spotted some menacing fifth-graders throwing rocks into a bush. I slowed down out of curiosity, though I tried to appear nonchalant, as these were boys who would certainly slug you in the stomach unprovoked. As I strolled by, a miserable screech echoed from the shrub. The boys chuckled. I knelt down to see a terrified, pregnant gray tabby. The cat was trying to hide and had become entangled, looking defenseless and defeated. Our eyes locked, and she seemed to wonder if I, too, was an attacker.

Would these older kids beat me up if I intervened? Unsure of myself, I forced a smile, making them think I might join in the fun while pondering my options. Should I find my brothers or call Mom at work? Should I flag down a cop or knock on the nearest door? The boys had run out of rocks and began chucking sticks and dirt clods at their target, trying to drive her from the bush. What would they do then? I knelt down again, and she looked up at me, full of anguish.

Suddenly oblivious to the junior sadists, I dove under the bush and reached through the low, dry branches to unsnarl the fat cat without squishing her stomach. It wasn't easy; she wailed and tried to claw me, but I managed to pull her free and scoop her up. Without looking back, I dashed across the street and ran home with the squirming bundle, telling her that she was safe and desperately trying to keep calm so I wouldn't call attention to myself in front of the neighbors; our apartment complex didn't allow animals.

Just before dawn the next morning, my disheveled new friend, who I called Duchess, announced her labor with a shriek from inside the closet. Patrick, Mike, and Mom watched from across the room while I lay on my stomach on the shag carpet just outside the half-open closet door to watch the kittens come out. As Duchess dutifully licked the afterbirth off each of her babies, I wondered if she'd devour any of them. "Sick kittens taste like chocolate so the mama cat knows to eat them," a friend had told me. All six were keepers. Oddly, just after the last soggy kitty was out, Duchess gripped her fourth-born by the scruff of his neck with her teeth and, purring wildly, set him down in my hands before positioning herself to nurse the others. He was all white, and I named him Harvey before placing him back down among his siblings. Duchess craned her head to nuzzle my arm and looked at me with pure gratitude. It was a bigger rush than sneaking into an R-rated movie.

Our reputation as the neighborhood "animal people" quickly grew. Not long after we took in Duchess, a kid from across the street knocked on our door to report that a cat was crying on the roof of the school and couldn't get down. Patrick rushed over, climbed up, and brought her home. That was Bridget, another pregnant cat. She needed an emergency Caesarian section that we could ill afford, but somehow did.

Then there were the alley cats who hung out near the smelly Dumpsters behind our building. Some accepted our open invitation to come inside and play, but others kept to themselves, which made us fearful that they'd fall in with the wrong crowd. Like the guy down the block who hurled newborn kittens against a stucco wall like a baseball pitcher practicing his fastball. Or the teens that crushed cats' skulls in the heavy Dumpster lids just for fun. Or the man who strung up fishhooks just inside the torn garage vent to ensnare any cats that might get paw prints on his shiny red car (he and the landlord were at odds over who would replace the vent screen). Yet another danger the felines faced involved our new neighbors: culture-shocked, war-weary refugees from Vietnam who reportedly cooked cats for dinner, just like back home. We learned that life for strays isn't really like Disney'sAristocats, so we started a sort of indoor sanctuary. Within months of taking in our first animal, we had a litter in each bedroom closet, plus a few older stragglers, for a grand total of seventeen cats and a dog -- in an apartment that didn't allow animals at all.

"I know what it's like to be a stray," Mom told each newcomer with a kiss.

We didn't consider animals pets, but affectionate vagabonds who became members of the family. Although they were lots of fun, we didn't take in animals for our own amusement, but to keep them from the various dangers we'd become aware of. We wouldn't have thought of buying a cat or a dog at a pet shop or even getting one from a shelter, as there were so many four-legged refugees in our neighborhood to tend to. It was a natural extension of our civic-minded outlook.

Although friends from school were envious of our motley menagerie, their parents and most of our neighbors thought we were crazy. Why care about animals when you barely have enough to eat yourself? Instinct, I suppose. Each cat got bathed, spayed or neutered, and a trip to the vet at any sign of illness, even if that meant bouncing a check. We couldn't imagine turning away some bedraggled cat in need of a feline leukemia shot simply because we didn't have the cash.

By the time I was in fourth grade, we had become conscious of every penny, often probing the couch seams for lunch money. Although Dad, who had moved to Florida, was always prompt with child support and alimony and Mom made okay money as a bookkeeper, we had an ever-increasing number of mouths to feed and vet bills to pay. Whenever a knock fell on the front door, we peeped through the bathroom window before answering in case it was the landlord, in which case we'd pretend we weren't home; he was either looking for overdue rent or hoping to witness the Wild Kingdom as grounds for eviction.

Patrick, at six, was too young to work, but Mike and I found odd jobs to help with family finances. For a time I delivered our local paper, theDaily Pilot, which we called theDaily Pile-of-it. It was invigorating to get up at four, ride around tossing papers from my bike, and be home in time to watch cartoons, get ready for school, and read the paper. My favorite column was the Police Blotter, which reported crimes such as DRUNK TEEN ARRESTED WHILE FIGHTING WITH TREE. Alas, I got canned when thePile-of-itlearned I wasn't yet ten years old. Next, I got an afternoon job putting flyers for Gene Ray's Sun-O-Rama tanning salon on car windshields in mall parking lots. That gig was over when South Coast Plaza security stopped me and made me backtrack, taking all the flyers off; I had no idea it was not only an under-the-table job but also unauthorized. I finally found more lasting employment making $25 each weekend at the Swap Meet in the Plant Bus. It was a converted school bus, painted green, which did brisk business selling everything from cactus to wandering Jews. It was run by a friendly hippie who wore tight, grimy blue jeans. During slow times he would occasionally tell me he was horny; I had no idea what he meant, but simply replied, "Cool."

This extra money barely made a dent -- we needed to hit a jackpot. Luckily, that's just what happened shortly after my favorite game show,Joker's Wild, announced during the closing credits that it would have kids on during the holidays. I was so thunderstruck I nearly choked on a Pringle as I jumped for the phone. The lady who answered at CBS said to write, as instructed on the screen. I hurriedly sent in the required postcard and followed up with pushy calls after school until they told me when the tryout was. Mom took off work, and we giddily drove to L.A. for the cattle-call audition in a busy, sweaty office. I don't remember what they asked; I think they just wanted to make sure the dozen brats they picked from the thousands who applied wouldn't be introverted wallflowers when the cameras came on. Somehow, I passed. This was my first lesson in persistence paying off, and even though it was just a game show, the experience became a big confidence builder for loftier endeavors. With our spirits through the roof, the whole clan got dressed up in our Pick 'n Save finery and went to Coco's Coffee Shop, where Mom bounced a check for a celebration dinner.

For my television debut, in December of 1973, I had long, bushy blond hair and wore an orange velour shirt that zipped halfway down the front and had a big floppy collar. This was accessorized by a polished purple rock dangling from a chain around my neck, a good-luck charm given to me by a friend of Mom's. CBS Television City was thrilling; in the elevator we saw Lee Merriwether with curlers in her hair, getting ready for aBarnaby Jonesclose-up, no doubt, and Dick Shawn, who was in two of our favorite movies,The ProducersandIt's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World. On a nearby soundstage,The Sonny and Cher Comedy Hourwas being filmed, and some of the cast came over to greet us tykes. I was mesmerized by Cher, who seemed like a gracious giant when she leaned over to ask if we liked the salami sandwich tray CBS had provided. I politely nodded, my cheeks bulging like a hamster's with the free grub.

On the show, Mom sat next to me, and my opponent, a pleasant twelve-year-old brunette, sat with her dad. She lost. The only question I got wrong was "Is Chicago's baseball team called the White Sox, Red Sox, or Blue Sox?" If only the sports question had been about Roller Derby. Still, I won; among my prizes were a candle-making kit (loved it), a set of encyclopedias (read 'em obsessively), ten tickets to a hockey game (too bad I didn't have ten friends and didn't care about hockey), a train set (never arrived), and $375 cash with which to buy a college savings bond. As if. That money covered vet bills instead, but Mom surprised me a decade later by giving the money back when I moved to Italy.

Too bad I didn't win a car; our sputtering 1965 Galaxie 500 had entered an automotive black hole, and we couldn't afford to bring it back. Then things turned worse when the landlord told us, "Either the animals go or you go." We went. The problem was how to get there without a car. Fortunately, we found another apartment only a few blocks away.

The evening before we moved, Mom dispatched Mike, Patrick, and me to the Pantry supermarket to snag shopping carts from the lot before they were rolled in for the night. The next morning we began the daylong task of moving all our belongings from Coolidge Avenue to Filmore Way in noisy grocery trolleys. Rattling over sidewalks, we pushed load after load of pots, pans, records, lamps, linens, and, worst of all, heavy books. Mom ignored our pleas and wouldn't throw out even one volume of her hardcover collection of Will Durant history tomes and Agatha Christie novels. Despite stares from our neighbors, she tried to make light of our plight by telling us we were stars in our own sitcom.

"Your friends will never be able to do this," she assured us.

Wheeling around corners was a challenge, but Patrick and I had fun speeding back in the streets with the empty carts. Mike wasn't the least bit amused, however, especially when we had to rumble our already-battered piano over curbs and speed bumps en route to our new abode. Clanging along the cracked sidewalk, the piano played its own artsy sonata, announcing our arrival to our new neighbors, who all came outside to investigate the racket. As the sun set, we clandestinely paraded back and forth many more times, each with a cat concealed under his jacket.

The next Thanksgiving we touched bottom: insufficient funds left us not only without a car, but also without power. Never without a solution, Mom arranged for a restaurant a few stops down the Baker Street line to cook our turkey. On holidays, buses run infrequently, so Patrick and I had a long wait with the heavy broiler pan until the number 32 pulled up. Mike was spared bus duty because he was still reeling from embarrassment at having to ride the raw gift turkey home from Mom's office on his bike, his backpack oozing thawed bird juice; he rarely enjoyed the escapades that can ensue when you are penniless.

No electricity meant a charming candlelight holiday dinner. Customarily, we lit a candle only when somebody died, whether family, friend, or a favorite celebrity. The whole candelabra blazed when Vivian Vance passed. It was one of the few rituals Mom upheld from a Catholic foster parent, along with crossing herself when we drove past roadkill. The glow of the candles made the meal seem more like an eerie Halloween party than a traditional Thanksgiving dinner, which felt right, as we were moreMunstersthanWaltons. In any case, we were a family. Mom poured just enough cheap red wine into our 7-Up to turn it pink, and Mike carved the turkey as thankful felines ringed the table for scraps, their silhouettes flickering against the walls.

Nowadays, people often ask how I maintain such a lighthearted outlook in the face of so many dire scenarios in the fight against animal cruelty. I think my upbeat demeanor stems from these destitute days, when no matter how bleak and hopeless life seemed, we still had more fun than anybody else. I think it's an ingrained form of gallows humor. Once, as a cashier in a busy grocery store checkout line was about to announce that our check was no good, Mom whispered to me to pretend I was suddenly ill so that we could rush out, leaving our full cart behind and saving ourselves the embarrassment of being publicly branded deadbeats. I began gagging as if I was about to vomit, with Mom exclaiming, "You poor dear!" as she quickly shepherded me outside, where our feigned anguish turned into genuine laughter. Laughing sure beats crying, though we certainly did some of that, too.

Mom almost never dated, as she wasn't much interested in romance, had no patience for small talk, and didn't really like many people. My father, on the other hand, got rehitched shortly after moving east, to a sunny New Jerseyite named Joan, who debunked any wicked stepmother myth I'd ever heard. To get to know them better, and to satisfy my urge to sample normal middle-class life, I lived with them near Tampa when I was ten.

Mindful of the fact that I'd be living under a roof in which a couple slept in the same bed, Mom discreetly carted me to Colony Kitchen to explain the facts of life. She had already told my older brother Mike, who begged her not to tell me, because, as he said, "Danny will always bring it up when we're trying to eat." I was tingling with excitement over the incredible secret I was about to hear, which Mom said had something to do with eggs. We asked for a corner booth, and in keeping with the mysterious theme I ordered an egg salad sandwich. When the waitress left, Mom leaned over the table to explain how penises and vaginas do business together so that an egg can get fertilized and become a baby. My interest quickly turned to disgust, and I wished I'd ordered something else. Mom quietly elaborated, but hushed up when the waitress brought our order. I reluctantly bit into my sandwich, but couldn't swallow, letting the glob of reproductive foam perch on my tongue. What the hell was I eating? I spit the goo into my napkin, dashed to the bathroom, and rinsed out my mouth. I never did learn exactly how it all works, and forever lost my taste for eggs.

I relished the easygoing year with my dad in Florida. I'd hang out at the Steak & Brew restaurant he managed, eating giant croutons from the salad bar and watching customers sip cocktails and shuffle through the sawdust that decorated the floor while Carole King'sTapestryeight-track played. When his shift ended, we sat together. Dad had scotch, Joan had white wine, and I drank Shirley Temples with extra maraschino cherries, although Dad always let me sip real booze. He and Joan both felt that if alcohol was totally forbidden, kids would secretly dive for the bottle.Cheers. At home, we often sampled Dad's collection of fruity liqueurs. Once he impressed us by igniting a bowl of apricot brandy, which shattered as he carried it to the table, setting our beige carpet ablaze.

Nagging Dad and Joan to quit smoking was my first pressure campaign. I didn't know or care about it being an unhealthful habit; I was just repelled by the smelly ashes floating about. Sometimes I'd roll up their Salems in the car window to crush them. When they bought more, I'd sway in the backseat and sing in a French accent, "Allouette, put out ze cigaretta, allouetta, because it make me seeck." They eventually stopped.

On Friday nights, Dad took me to synagogue. To please him, I feigned an interest in Judaism and even attended Hebrew school, though I never really felt like I belonged to "the chosen people." One of our first assignments was to write hate letters to Nixon, protesting Egyptian president Anwar Sadat's Middle East peace plan. I felt uncomfortable writing such angry letters about an issue I barely understood. Couldn't we write protest letters to NBC for cancelingLaugh-In? I dropped out but didn't hang up my yarmulke for good -- I went to countless Passover seders and Rosh Hashanah parties, where, luckily, nobody could tell whether I was drinking grape juice or Manischewitz.

Myidea of a truly religious experience was bowling. On Saturdays, Joan drove me to junior bowling league, where I sometimes bowled 200 with a sparkly purple ball that matched the necklace that had brought me such good fortune onJoker's Wild. I've always found the entire bowling experience enchanting: the cozy lighting, the din of pins violently crashing about, the seedy cocktail lounges, and especially the lovable oddballs who work and play there. One kid in my league taught me to phone the attendant and ask if he had ten-pound balls. "Wear baggy pants and they won't show!" we'd yelp before hanging up.

On Sundays, Dad and I were often up before dawn to go pier fishing in Daytona. Live bait intrigued me. You had to grip the minnow and slide the barbed hook through his gilljust so, or you could stick him and his heart would race under your thumb and guts could gush all over your hand. It was a real-life game of Operation. Another method involved puncturing the minnow at the ridge of his back and dangling him like a puppet before tossing out the line. Once in the water, when the hooked minnow would pull hard, I would try to imagine what kind of sea monster might be about to chomp down on him. More often than not it was a disappointing mackerel, which we'd throw back. Seeing the trace of minnow on the hook made me feel bad.

At least I haven't killed the mackerels, I reasoned, just ruined their day.

Copyright © 2007 by Dan Mathews

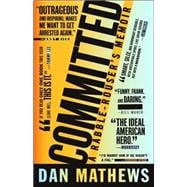

Excerpted from Committed: A Rabble-Rouser's Memoir by Dan Mathews

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.