The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

Harvey Blissberg seemed to be walking a plank of his own making. He had been out of baseball for fifteen years and out of sorts for the last six months. After ten years spent as a private investigator followed by four forgettable ones as a motivational speaker, Harvey felt he was slowly marching himself at cutlass-point toward an early demise. Lately he had spent much of his time on his Cambridge sofa, watching old sporting events on ESPN's Classic Sports Channel and documentaries about the history of baseball.

When the phone rang, he paused a documentary called When It Was a Game that he was enjoying for the third time that week, brushed the tortilla chip crumbs off his shorts, and croaked a hello into the receiver.

"Professor?" a voice said. "That you?"

Professor. No one had called him that for years. It was like hearing a childhood nickname called out at the end of a very long hallway.

"Felix?" Harvey said, meaning Felix Shalhoub, his manager during his last year in the majors with the expansion Providence Jewels, and now--Harvey still followed the game just enough to know this--the franchise's general manager.

"Yeah, yeah, it's me. How are ya?"

"Outstanding."

"Good to hear your voice. I heard you were doing some motivational speaking."

"Not anymore."

Harvey had been possibly the least motivated motivational speaker ever to address three hundred pharmaceutical salesmen in Orlando or three dozen managers of export documentation for dangerous cargo in Bayonne, New Jersey. How had this happened, that a man who prided himself on his avoidance of cliché should end up peddling platitudes about courage, teamwork, and the will to win? Because a man named Cromarty, who operated a second-rate speakers' bureau in Boston, had heard Harvey address a group of high school coaches and told him that midsize companies who couldn't afford Norman Schwarzkopf or Fran Tarkenton would still shell out good money for a tall, personable former major-league outfielder with good teeth to pump up their troops.

Cromarty's proposition came at a time when Harvey had lost interest in exploring the bleaker secrets of his fellow human beings. It turned out there was a limit to the amount of evil a man could investigate, even at a certain professional remove, without eventually feeling contaminated by some virus of moral degradation. Before Harvey knew it, he was on a plane to the first of many sales meetings with themes like "Simply the Best," "The Future Is Now," and "Tomorrow's Our Middle Name" to explain to a ballroom of captive employees the fundamentals of a positive outlook that Harvey himself had never quite mastered. When he was through spewing slogans, there was invariably a stampede of grown men to the podium. They peppered him with questions about his baseball exploits, which they remembered far better than he, or tried to solicit his predictions for various peppered races and free-agent signings. It was depressing to Harvey that so many otherwise functional adults would want to shake the hand of a .268 lifetime hitter. And finally, he was out of that game too.

"You still with Mickey Slavin?" Felix asked.

"Still together, still not married. You know, she's now a sideline reporter for ESPN. She's on the road a lot." Fifteen years ago, when they met, he had been the star and she had been an oddity--a female sportscaster, albeit in Providence's tiny market. Now she was on national television, and he was--well, he was on the sofa, merely watching it.

"Now that you mention it, I feel I've seen her around the league this year."

"So how's the team doing?" Harvey asked.

"Whaddya mean, how's the team doing? You don't follow the game anymore?"

"Oh, off and on."

Where to begin Harvey's list of grievances with the national pastime? Overentitled players, selfish owners, and soaring ticket prices that left many ordinary Americans outside the ballpark. Worse, the game itself was buried beneath an avalanche of inane sports talk radio, round-the-clock cable coverage, and merchandising of team apparel and vintage sportswear. The game seemed to Harvey little more than a sideshow, the raw material for the finished product, which were the highlights that ran around the clock on several channels, a frenzy of home runs and annoyingly complex graphics. Instead of being a refuge from the clutter of daily life, baseball was now just part of that clutter.

"We actually got a shot," Felix was saying. "And thanks to Cooley we're selling out. His streak's the biggest thing to hit Providence since the hurricane of `thirty-eight."

"I see where he's flirting with history."

"More like French-kissing it. Last night he pulled even with Pete Rose and Wee Willie Keeler."

"Twelve more, and he'll do the unthinkable," Harvey said.

"The Daig," Felix said in a reverential whisper. "Joe DiMaggio."

Whose very visage had appeared moments ago on Harvey's TV screen. The documentary he'd been watching consisted of 8- and 16-millimeter home movies of baseball players, games, and ballparks shot by players, their families, and fans between 1934 and 1957. It was like opening up a box of old baseball photographs to find they had all come quietly to life in faded color: DiMaggio himself, Gehrig, Ruth, Robinson, Greenberg, Dickey, even old-timers like Honus Wagner, Ty Cobb, and Cy Young, all liberated from their black-and-white prisons, yet still innocent of television and everything it would do to the game, to the very expressions on men's faces. The home movies gave these players a particular poignancy, a simple clowning humanity.

The documentary captured some of the game's now forgotten rituals: comical pepper games, train travel, afternoon crowds in hats, ties, and fur stoles. In the 1940s, ballplayers were still leaving their gloves--poor little scraps of leather--on the field rather than carrying them to the dugout, as if to say the field was hallowed, as if leaving a sacred piece of themselves there until they returned. Harvey had retired in the 1980s, much closer to the present than the days the documentary depicted, but it was only with the grainy, earnest realities of baseball's past that he felt any connection at all.

"You wouldn't recognize Rankle Park, not since Marshall redid it and renamed it The Jewel Box. We're packing 'em in. It's a real carnival atmosphere."

This was pure Felix. The hoary bromides of baseball were his specialty; "carnival atmosphere," "a real donnybrook," and "a day late and a dollar short" just rolled off his tongue. Not that Harvey was anyone to cast the first stone; he'd made a living off the clichés of competition for the last few years. He'd even stolen a few of Felix's.

"You want to know something funny, Felix? I used to use a few of your favorite sayings in my motivational speaking."

"Be my guest."

"Remember that sign you had in the clubhouse? `Winners Are People Who Never Learned How To Lose.'"

"I believe that with all my heart."

"I know you do, Felix. And that's why I passed it on to thousands of office supply salesmen across this great country of ours."

"You doing okay, Professor?"

"I'm fine." But the fact that he was wearing an embroidered polyester-blend Mexican shirt with four pockets suggested otherwise, that dark forces were at work. Of course, he could try to justify the guayabera on the basis that, in early middle age, he needed more pockets than ever: for reading glasses, cell phone, bottle of Advil, tiny address book for numbers he could no longer remember, the TV remote control, a tin of Altoids. But the fact was that his sartorial style, which Mickey referred to as "a lot of denim, a little suede, and a great deal of olive green," had taken a nasty, leisure-wear turn. Time had swallowed him up, as he had seen it do to other middle-aged men.

"Look," Felix was saying, "all the more reason for you to come down and see me tomorrow night. I want to talk to you about doing some work for us."

"Do what?"

"We want to hire you as the team's motivational coach."

"You can't be serious."

"A team that's on the verge of winning might as well be losing if it can't get over that last hump of inferiority."

"You just make this shit up, don't you?"

"I need you down here, Professor, to gas these boys up."

"I've been out of baseball a long time, Felix."

"Which gives you that important fresh-blood factor."

"My blood is very tired at the moment."

"That's because you're not out here at the ballpark, where you belong."

"Right here on my sofa is where I belong."

"I'm talking about showing these overpaid boys how to put the finishing touches on their self-esteem. I'm talking about instilling in these boys the peace of mind needed for victory. I've cleared it with Marshall."

"I have nothing to say."

"You're underestimating the value of your experience."

"Don't be so sure."

"I want you to come down here to The Jewel Box. I'm offering you a free skybox seat to a game you'd never be able to get into otherwise. We'll sit and drink Narragansett and talk about my proposition, and you'll see how you feel about this great national pastime."

"I know how I feel about it."

"I'll leave your name and a pass to the owner's box at the Will Call window. Campy would love to see you."

"Campy Strulowitz? I thought he was dead."

"He is dead, but he keeps showing up at the ballpark, so we figure we might as well just let him coach third base."

Harvey laughed, perhaps for the first time in weeks. Felix Shalhoub and Campy Struiowitz still working for the Providence Jewels? After all these years? It was like hearing your family had survived a tornado.

"So it's a deal?" Felix said.

When Harvey got off the phone, he took a long swig from the quart bottle of Gatorade he kept on the end table and stared at the image on his television screen, frozen in pause mode: it was President Eisenhower throwing out the first ball at a Senators' opener in Griffith Stadium. Eisenhower, the Senators, Griffith Stadium--all gone now.

For the first time in a while, Harvey remembered what it was like to stand three hundred feet from home plate and pick up the flight of a ball the instant it came off the bat, how it felt to be connected by a thread of pure desire to that sphere as it rose and cleared the background of the upper deck, arching against the summer night sky as he sprinted deep into right center, Harvey already knowing, with a certainty that was wholly lacking in his present life, that he would consume the ball in full stride a few feet from the warning track and feel the warmth of the fans' applause on the back of his uniform jersey as he loped, full of humble triumph, back to the dugout.

Harvey bit off the corner of a tortilla chip and chewed it thoughtfully. He had the sinking feeling he was about to push himself off the end of the plank, into his shark-infested future.

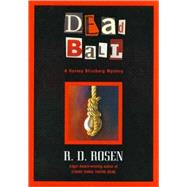

Excerpted from Mean Streak by R.D. Rosen. Copyright © 2001 by R. D. Rosen. Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.