What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter 1

On April 17, 1861, I enjoyed the sensation of one whose birthday falls on Christmas. I woke unusually early, along with everyone in the Commonwealth of Virginia. That day our legislature was to vote on secession -- a crisis that had begun as a whisper among gossipmongers not a year prior but had grown with the frenzy of a revival into a statewide obsession. The newspapers had for weeks detailed the debate in Richmond, from the rhetorical thrusts and parries at the statehouse to the curt and somber replies of Mr. Lincoln, whose anointment the previous autumn so inflamed the passions of our men.

As a youth of fifteen, I had not been involved substantially in the secession crisis, but I enjoyed the high drama of the proceedings, and I followed them with a greedy eye. Earlier that spring my father had hosted a meal for our delegate and a dozen men of business. The ostensible purpose of the gathering had been to gauge local support for secession, but these being men of practical appetites, the talk soon turned to the prospect of war and the demands this might place on our local mills and factories. "If there is any fighting," the pompous delegate announced, "it shan't continue long enough to bring any lucre hereabouts, fellows. The Yanks know our purpose, and they know our differences, and they will respect our intention sooner or later. The thought in Richmond, I must tell you, is that they will be too blanched to fight." The men laughed and clapped one another on the back. This I observed from the sanctuary of our kitchen, where I had finished helping Mother and Peg with the service and was eating my share at the kitchen table.

The delegate -- his name was Coggin -- was distinguished by a pair of unruly snow white eyebrows that sprung from his face like owl feathers. He was a consummate politician -- which is to say he was given to expedient speech and lacked even a vestigial spine.

The telegraph from Mr. Coggin, who was in Richmond for the vote, arrived at the Lynchburg post office just after one o'clock. I had spent the morning in the square, pitching horse-shoes with some other boys. Though it was a Wednesday, we had not shown our faces at school, feeling assured that a Special Circumstance excused us from truancy.

The taverns along the square were packed with a rare noonday crowd. Like me, these citizens could not bear to wait any longer for the news than was absolutely necessary. However, decorum mandated that these men not be seen loitering with boys in the street, so they made pretenses at business and meal taking. The tavern doors could almost be seen to bulge with the swell.

At the doors of the town stable, across the square from the post office, a circle of five or six Negroes gathered in idle chatter. As Wednesday was seldom a slave's day at liberty, I assumed that these had been sent by their masters to await the news and carry it back post-haste. Indeed, the animals in the first stalls were ready in saddle, with reins tied quickly to the rail.

Just after the one o'clock bell the post office door swung open and the postmaster -- a wasted but well-meaning old man by the name of Tad Keithly -- strode out onto the top step. Those of us near enough saw his smile ablaze, and we could guess the news. In truth, though, no one ever questioned what the news would be. "I have word from Mr. Coggin!" the postmaster shouted generally -- the taverns having emptied into the square, so that his audience numbered well into the hundreds. "The votes are in, and they are eighty-eight in favor, fifty-five opposed." He paused and let that little bit of silence grow like the drop of melt at the tip of an icicle. "Gentlemen, we have it! God bless the unencumbered Commonwealth of Virginia!" And then Keithly's eyes began to water. Indeed, all around me grown men began to weep and embrace one another. I saw that it was not regret in their tears but rather the opposite. With unbridled joy men commenced to cheer and whoop and fire their pistols into the air. I hollered from a place deep between my lungs, but the crack of gunfire obscured my voice. I did not know if I was creating any sound at all.

The air reeked with the acrid tang of powder. My nose filled up with dust from the street as horses thundered out of the stable. I ran to the door of the nearest tavern to avoid being trampled. A few men remained inside the tavern, and I recognized several as business acquaintances of my father, men who had been present at our dinner with Mr. Coggin. The eldest of these, a man whose mustache puffed out over his lip like a squirrel's tail, stood up to begin a toast. I could not hear his words, but several times he brought laughter from the group and had to pause. At last he raised a bottle of whiskey above his head. As the others cheered, the old man put the bottle to his lips and drank a ten count. When he pulled off, a runnel of brown liquor leaked from the side of his mouth and he wiped it with his starched white cuff.

Taking heed not to fall into the path of a messenger's horse, I picked my way to the other side of the square, beyond which I would hasten home. On Wednesdays the street that led most directly from the square to our neighborhood was filled out with grocers' stalls, and it was in front of one of these that I was stopped by a flat hand in my chest. A white farmer obscured my path. His beard was shot through with petals from the spring lungwort. After a moment's consideration of my face, he lowered his hand and plunged it into a sack hanging at his side, from which he removed a yellow rose. "God bless," he said, and he handed me the flower.Copyright © 2008 by Nick Taylor

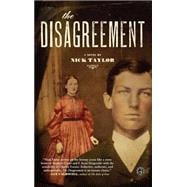

Excerpted from The Disagreement by Nick Taylor

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.