Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

We stayed on State Route 51 south from Carbondale, following a map Amy scrawled on the back of SCLC stationery as Smith did impersonations of the waitress Arlene and the old man in the Pit Stop. He was a remarkably talented mimic, I realized during the rest of the ride, and so scathingly funny in his interpretations that even while Amy and I laughed until tears cascaded down our cheeks, which helped me forget for a while my shame at the damage I'd done to the diner (every police car we passed made me squirm down in my seat), I was afraid to think of Smith applying his imitative skills onme.The possibility of seeing things as he did, from the oblique angle of alienation, fascinated and frightened me at the same time; he was so antithetical to King, yet in some ways I saw in Smith the distillation of the minister's message to a black student he met at Lycoming College in Pennsylvania, a young man so consumed by anger and hatred and dualism that all King could say was, "Son, the best thing you can do is try to understand yourself." Smith forced me to think on this, to turn it over and over, and inspect it from every side: My Self. Yet for all his similarities to King, his talk earlier about envy and divine rejection put me on edge -- indeed, had briefly pushed me over it. My skinned knuckles were sore and I'd cut my left forearm when smashing bottles on the counter. In other words, I'd injured myself quite as much as I'd wasted the Pit Stop. And it was his -- Chaym Smith's -- doing. But slowly, as I saw him slip effortlessly into Arlene's physical eccentricities, I began to feel that, for all his exasperating qualities, perhaps he could stand in for King, and told him so.

"Sure, I can mark him," he said. "That's easy. Everybody's playing a role anyway, trying to act like what they're supposed to be, wearing at least one mask, probably more, and there's nothing underneath, Bishop. Just emptiness..."

The Chevelle coasted down a dusty road trenched between enormous trees that domed overhead, breaking sunlight into flecks of leaf-filtered brilliance that flickered on a road that wound past a dilapidated Methodist church and ended in front of a rough farmhouse. It seemed to spring up suddenly out of kudzu vines and broomsedge, a one-story structure erected on rocks: it floated above these huge stones like a raft, shadowed by a double-trunked oak tree in the yard. Paint on the front porch was peeling away in large strips like sunburned skin. The yard, wild with windblown weeds, was as uncultivated as a backfield full of burdocks and snakes. I cannot say I was relieved to arrive at this remote, rural destination. The heat was withering. Out there more than two miles from the highway, and possibly three to the nearest store, there were none of the distractions to rescue a man at night from the feelings and thoughts he least wanted to confront.

Or from the strangeness of Chaym Smith.

Skeptically he squinted at the dilapidated house. "Anybody living in this dump?"

"Not this summer." Amy's brow pleated. "And it's not adump.Mama Pearl rents it out to kids over at the college. At her age she doesn't like to live so far from other people. It's furnished inside and she's never asked for more than what she needs to pay the taxes and keep her place upstate, but it's been empty since June. That church we passed up the road? Most of our family is buried in a cemetery there..."

Smith cut off the engine, and we unloaded the car, lugged boxes inside to dusty rooms with drop cloths covering the sparse, old-fashioned furnishings while Amy explained that her great-grandfather James, a preacher, framed each room and drove half the nails in the farmhouse as well as in the church just a quarter mile away.

Talking about her family was a natural, innocent enough thing to do, and she could not have known, nor I, how it would draw out even more of Smith's cynicism. Taking a deep breath, he said, "Is this gonna be alongstory?"

I shot him a stare to shut him up as Amy opened stiff chintz curtains in the front room, flooding it with light. "Go on," I said. "You were saying something about your great-grandfather. What was he like?"

She was silent, looking around the room, remembering, and I was struck again by her beauty, the melic lift of her voice when Amy said she didn't know her great-grandfather all that well, but his daughter, Mama Pearl, often invoked her father as industrious and loving and quick to load his rifle if he caught the faintest trace of discrimination directed at either his kin or himself, though as a family the Griffiths seldom came into contact with whites, no more often than did, say, the Negroes who founded the town of Allensworth in California or other all-black hamlets at the turn of the century. Whites may not have liked them, but James -- her grandmother told her -- never asked to be liked, only respected. And that was a matter fully within their own control. They grew their own food before and after the crash that crippled the nation in '29. They operated a school for their children at the nearby church, one so successful in teaching metalwork that its graduates were considered the best smiths in the county and had work come rain or shine in the twenties.

Amy walked us through rooms of antique furniture -- ladderbacked chairs, heavy oak tables, an old black walnut Jefferson bookstand fastened with mortise-and-tenon joinery -- and for me it was like being gently led into the past, a distant, better time when black people were the moral fiber of a nation. She said that during her visits in the 1950s to Makanda nothing pleased her so much as how self-reliant her relatives and their neighbors seemed. There were inconveniences, of course. Water came from a well. Thirty paces from the back door was an outhouse she hated to visit in the middle of the night. But she loved seeing her kin making their own clothes and furniture and bartering with other black people in the area for the little they could not produce themselves. She remembered her great-grandfather, who, if he came across something he especially liked on his dinner plate, saved that portion of the meal for last; when he flipped through the newspaper and saw an item that interested him, he scanned everything else on that page first and held off satisfying his desire for that one particular news report until he'd made himself read everything around it. Throughout Jackson County her kin were known as the people black travelers should see if they were turned away from white hotels and needed a room for the night and a good meal the next morning. As might be expected, they had no tolerance for phoniness or pretense. They did not judge others by their possessions, dress, family pedigree, or how often they got their names in the newspaper. Family and friends came first. And they did not hesitate to share what little they had, whether it was food, labor, their home, or the skills each had developed in order to survive. She said they were known to hold on to a dollar until it hollered. (And James often discussed Negro entrepreneurs he admired, and urged his children to take as their example people like merchant Jean-Baptiste Du Sable, one of Chicago's earliest settlers, Madame Walker, Philadelphia's catering king Robert Bogle, and colored people who controlled America's service businesses before World War II, to say nothing of owning their own banks and insurance companies.) James's children, Mama Pearl and her two brothers, were never pampered. He insisted that from birth to age five his progeny be treated like princes and princesses, but after that they were to work like servants, even if what they did consisted in nothing more than fetching things for the other folks. (He suggested they sing as they worked to lighten the labor.) No, Amy said, he could not tolerate idleness, and it was not in his nature to ask anyone for anything.

As we traipsed through the old house, its floorboards creaking beneath our feet, Smith responded to Amy's family history with a contemptuouspfft!from his pursed lips, which puzzled me, because I almost felt that as Amy spoke I could hear her ancestors' day beginning with breakfast-table prayer, which did not exclude even the youngest children; they had to know chapter and verse before their twelfth birthday. There were no spirits in this household. In my mind, I saw James -- a tall, dark-skinned, suspender-wearing black man -- insisting that his two sons and daughter, Amy's grandmother, acquire as many skills as they had fingers on their hands, work for everything they received, and treat whatever possessions any family member had as carefully and conscientiously as if they belonged to someone else who one day might ask for their return. The family, he told them again and again, was far more than a group bonded by blood. More even than a collective that insured the survival of its members. More than anything else, according to the Griffith patriarch, it was the finest opportunity anyone would have for practicing selflessness, for giving to others day in, day out, and for this privilege, this chance to outgrow his own petty likes and dislikes, opinions and tastes, he gave abundant thanks. If they wanted to be happy, he counseled them, the first step was to make someone else happy. Through Amy's words I saw him demand that his children read after their chores were finished -- what, he didn't care, but he wouldn't talk with them if two days had gone by and they'd not touched a book. (Smith was looking at his watch, frowning heavily; her story so displeased and rattled him that he entered one of the bedroom doorways at the same instant I did, and for a second we were stuck, shoulder to shoulder, our arms pinned at our sides, Chaplinesque, until I jerked free.) Eventually, she explained, the farm could not sustain itself. By the late 1950s, his sons left to find work elsewhere. Mama Pearl did the same, moving to Chicago, where she was steadily employed at Fanny's Restaurant in the suburb of Evanston, and possession of the property came to her when her mother died in 1963.

Now we were in the kitchen. Smith glowered darkly out the window, cracking his knuckles. I tried to ignore him. I said to Amy, "Your people lived like that?"

"Yes."

"I wish I'd known your great-grandfather." In the depths of me I did. Partly I was envious, knowing so little of my own family's past before they migrated from the South to the city; and partly I hungered for the sense of history she had, the confidence and connectedness that came from a clear lineage stretching back a century. "He sounds like a wonderful man."

"He was." Amy laughed. "Mama Pearl told me he used to say over and over, 'Life is God's gift to you; what you do with it is your gift to Him.'"

"Excuseme," growled Smith. "I need to shit."

Amy flinched, as though he'd pinched her. She pointed through the window to an outhouse about fifty feet from the back door. Smith seemed anxious to flee the farmhouse and had one foot out the door when she said, "Wait," reached into one of the boxes of SCLC materials we'd placed on the table, and brought out one of the Commitment Blanks distributed among volunteers. "I brought this along for you to sign."

I knew that form well, having signed one earlier in the year. On it were ten essential promises -- like the tablets Moses hauled down from smoky Mount Sinai -- the Movement asked of its followers. Seeing the form made me feel a little weak, insofar as I remembered the hundreds of times I'd failed to uphold these vows:

COMMANDMENTS FOR VOLUNTEERS

I HEREBY PLEDGE MYSELF -- MY PERSON AND BODY -- TO THE NONVIOLENT MOVEMENT. THEREFORE I WILL KEEP THE FOLLOWING COMMANDMENTS:

I sign this pledge, having seriously considered what I do and with the determination and will to persevere.

NAME

(Please print neatly)

He tore it from her hand and tramped outside, his action so rude -- so brusque -- that it startled Amy and angered me. I followed him into the backyard, clamped my fingers on the crook of his arm, and spun him round to face me.

"You want to tell me what's wrong?"

"That story she told," said Smith, "it's a fucking lie. Front to back, it waskitsch.All narratives are lies, man, an illusion. Don't you know that? As soon as you squeeze experience into a sentence -- or a story -- it's suspect. A lot sweeter, or uglier, than things actually were. Words are just webs. Memory is mostly imagination. If you want to be free, you best go beyond all that."

"Towhat?"

"That's what I'm trying to figure out. By the way" -- he held up the Commitment Blank and grinned -- "tell her thanks for this. I need something to wipe with."

I stood and watched him squeeze into the outhouse and shut the door. I picked up a handful of rocks and pegged them against the wall. Inside, Smith laughed. He reminded me I owed him for saving my skin in Chicago, and kept on talking through the door, railing against conformity and convention, all the while emptying his bowels loudly, with trumpeting flatulence and gurgling sounds and a stink so mephitic it made me choke, then fleeing back into the farmhouse, I found Amy looking through his bags.

Winged open in her hands was one of Smith's sketchbooks. She turned each page slowly, puzzling over verses he'd scrawled beneath a series of eight charcoal illustrations of a herdsman searching for his lost ox. Finding it. And leading it home, where -- in the final panel -- both hunter and hunted vanished in an empty circle. "Chaym is talented," she said as I stepped closer, looking over her shoulder, "but I can't see him helping the Movement. Look at these." She flipped through more pages, turning them carefully at the bottom edge, as if she were afraid the images might soil her fingers. But I was not seeing Smith's drawings. No. I saw only the softness of her skin, and before I knew full well what I was doing I encircled my arms round her waist and lowered my head to her shoulder in a kiss. Amy stiffened for an instant. Then I felt her relax, offering no resistance whatsoever to my embrace. She squeezed my arm gently, then stepped to one side and placed the sketchbook back on the kitchen table.

"That was sweet, Matthew, but please don't do it again."

"Why not?"

"I know you're attracted to me," she said. "Iknowthat. And I'm flattered. I really am. It's just that I'm not right for you. Or you for me. Your sign is water -- didn't you say that once? Mine is earth. Together, all we'd make ismud."She tried to laugh, to get me to laugh, as one might a child who has knocked over his water glass at the table and needs to be chastised but not crushed for his blindness. His blunder. She was not angry, only disappointed, I thought, and was doing her best to be gracious -- to salvage the situation for me and herself -- after the minor mess I'd created. And it was strange, I realized, how at that moment my emotions were a pastiche of pain and wonder at her civilized composure, her ability to absorb the discomfort and disorientation my desire caused her -- as if she were stepping over a puddle -- and at the same time transform it into something like sympathy for me, for how confused and aching I felt right then -- like someone who'd fallen off a ladder, say, or stepped on a rake. Yes, that was how I felt. Gently she placed her hand on my arm, and in a voice as full of candor as it was of Galilean compassion, said, "I'm fond of you, really I am, but I'm not the right person for you." Once again she smiled, as one might when a child is being unreasonable. "Someday, if you do well, you'll find someone right for you. I need somebody a little more like the men I knew when I was growing up. Or like Dr. King. Oh, God, I hope I haven't hurt you."

Actually I couldn't say; I'd never been shot down with such finesse before. Nor had I ever felt so impoverished by desire. Just then, her words were more than I could bear.

"We can still be friends?"

I couldn't look at her, but I said, "Sure." My eyes began to burn and steam, blurring the buckled, floral-print linoleum floor as she pushed up on her toes, pressing her lips against my cheek in a chaste kiss. "I suppose we should get back to unpacking, eh?"

"You go ahead, I'll get Chaym."

More than anything else, I needed to be away from the farmhouse. And her. It was dark now. My feet carried me east, from the kitchen to an open field. Looking back at the lighted rear window of the old, warm house with its family heirlooms and positivist history as it grew smaller, I felt better being outside, stepping through humus, round moss-covered stones green as kelp, past the well where the water tasted faintly of minerals, skinks, and salamanders. The brisk walk left me panting a little, perspiring as if a spigot somewhere in my pores had switched on, pouring out toxins in a tamasic flush of sweat that soaked my shirt. Yes, it still hurt. I'd always known I was hardly the model for Paul's Epistle in Corinthians 13, but to be rebuffed because I fell so short of the minister's example was confounding. Who could measure up tothat?Yet -- and yet -- in her refusal I also felt relief, as if the weight of want had lifted. I sat down in weeds high as my waist, the night closing round me like two cupped hands. Wondering less about the woman I'd desired than the mystery of my desire itself, how it had made me experience myself aslackand her as fulfillment, all of which were false, mere fictions of my imagination. Just beyond there were woods that looked vaporous and incorporeal in the moonlight; and I felt just as vaporous and incorporeal, as if maybe I might vanish in the enveloping, prehuman world around me. Leaves on the nearest trees trembled with tiny globes of moisture clear as glass. And then, as my eyes began to adjust, I saw numinal light haloing the head of a figure -- it was Smith -- kneeling amidst the trees.

His eyes were seeled, his breath flowed easily, lifting his chest at half-minute intervals and flaring the flanges of his nostrils faintly with each inhalation. His exterior was still as a figure frozen in ice. Yet inside, I knew from his notebooks, he was in motion, traversing 350 passages he'd memorized from numerous spiritual traditions, allowing the words to slip through his mind like pearls on a necklace. The passages -- calledgathain Buddhist monasteries -- ranged from Avaita Vedanta to Thomas à Kempis, from Seng Ts'an to the devotional poetry of Saint Teresa of Avila, from the Qur'an to Egyptian hymns, from a phrase in John 14:10 to the Dhammapada; they were tools -- according to jottings he'd made -- selected to free him from contingency and the conditioning of others. When he focused on agatha,thegathawas his mind for that moment, identical with it, knower and known inseparable as water and wave. He was utterly unaware of me, and his practicing the Presence, reviewing these passages like a Muslimhafiz,was so private and intimate an exercise that I felt like a voyeur and was about to pull myself away, back toward the farmhouse, when I saw tears sliding down his cheekbones to his chin.

Then his eyes were open, and he asked softly, "You like what you see, Bishop?" He wiped his cheeks with the back of his hand. "Yeah, I cry sometimes. Can't help myself. When I sit, it just comes out. I can't keep it down. At thezendo,I wasn't the only one who cried when doingzazen."

I stepped closer and sat down as he stretched out his legs from the kneeling position, massaging them vigorously to get blood moving again. "Where was that?"

"Kyoto," he said. "Two years after my discharge I was there, tossing down sake, and the fellah I was drinking with told me 'bout a Zen temple way out in the forest that accepted foreigners. 'Bout that time I was a mess, man. Drank like a fish. Hurt inside every damned day. I wanted to kill myself. Kept my service revolver right beside my pillow, just in case I worked up the courage to stick the barrel in my mouth and paint the wall behind me with brains. I went to the temple 'cause I was sick and tired of the world. I wanted a refuge, someplace where I could heal myself. I figured it was either thezendoor I was dead." Smith kept on massaging his right leg as he talked, working his way methodically from his hip downward.

"When I got there, I kneeled in front of the entrance, on the steps, and kept my head bowed until I heard the straw sandals of one of the priests coming toward me. I begged him to let me train. Naturally, he refused my request, like he was supposed to do, and then he went away. That's the script. So I sat there all day -- like I was supposed to do -- on my knees, my head bowed, keeping that posture and waiting. Night came, but I still didn't move. On the second day it rained. I was soaked to the skin. I damned near caught pneumonia on the second evening. But sometime during the third day the priest came back and gave me permission to enter the temple temporarily. See, he was playing a role thousands of years old same as I was playing mine. He had me wash my feet, gave me a pair of tatami sandals, put me in a special little room calledtankaryo,shut the sliding paper door, and went away again, this time for five days. For five days, I didn't see nobody. They didn't bring me food. Or water. I waited, kneeling just like you seen me doing, my eyes shut, hands on my lap, palms up with my thumbs kissing my forefingers, meditating for a hundred twenty hours nonstop to prove to the priest that I could do it. I say five days, but when you're inzazenthat long, there is no time. That's another illusion, Bishop. In God, or the Void -- or whatever you wanna call it -- past, present, and future are all rolled up innow.And the hardest thing a man can do, especially a colored man whose ass has been kicked in every corner of the world, is live completely innow.But I did. And the priest came back. He led me down a hallway with wooden floors polished so brightly by hand that they almost gleamed, then he stopped in front of a bulletin board listing the names of the monks and laymen presently training at the temple. Mine was the last, the newest one there. I tell you, buddy, when I seen that I broke down and cried like a goddamn baby. I was home. You get it? After centuries of slavery and segregation and being shat on by everybody on earth, I washome."

I did get it, and in his voice I saw the beautiful vision of a tile-roofed, forest temple encircled by trees, the grounds spotless, the gardens well tended, and here and there were statues of guardian kings. Smith began slowly massaging his left leg as he'd done his right, working from hip to heel.

"I was a good novice, I want you to know that. Every day I was up at three-thirty A.M. when the priest struck the sounding board. When I washed up I didn't waste a drop of water. I brushed my teeth using only one finger and a li'l bit of salt, and I was the first in the Hondo -- the Buddha hall -- for the morning recitation of sutras. After that, when we ate, I didn't drop nary a grain of rice from my eating bowl. I shaved my head every five days. Kept my robes mended. With the others, I walked single file from the temple into town, reciting sutras and collecting donations in a cloth bag suspended from a strap around my neck. Always I blessed those who gave, singing a brief sutra that all sentient beings may achieve enlightenment and liberation. But for that year I trained, I never touched money. Or thought 'bout women. Or drink. The world that hurt me so bad didn't exist no more, and I was happy. Hell, I wasn't even aware of an I. After our rounds we came back and didsamu-- monastic labor. Chopping firewood. Maintaining the gardens. And all this we did in silence, Bishop. Each daily task waszazen.Was holy. No matter how humble the work, it was all spiritual practice."

Smith had finished stretching. He scooted back from the spot where he'd been sitting and rested his back against a tree.

"What I'm saying is that my practice was correct. So good the Roshi promoted me to kitchen chef ortenzo.That's an honor, right? It means I'd been diligent. He put me in charge of preparing food to sustain theSangha,and I was 'bout the only one the Old Man, the Roshi, didn't whack with his bamboo stick when time came for him to interview me 'bout mykoan.

"It was great," Smith said. Then, sourly, "For a year."

"What happened? Why'd you leave?"

"Didn't want to." He laughed. "I felt like I was in Shangri-la. I coulda stayed there forever. But one year to the very day I started, one of the priests said the Roshi wanted to see me. I was in the kitchen, making a sauce to go with wheat-paste noodles. Lemme tell you, it wasgood.Li'l sea tangle, sesame seeds, ginger, chopped green onions, and grated radishes. I washed my hands, then hurried to the Roshi's room. I struck theumpan,the gong, to let him know I'd arrived, then entered when he called. I knelt before him, never lifting my eyes, but I wondered fiercely why he wanted to see me. Had I done wrong? No, he told me. My practice was perfect. The other monks respected me. But (he said) I was agaijin.A foreigner. Only a Japanese could experience true enlightenment. That's what he said. He didn't want me to waste my time. He was being compassionate -- see? -- or thought he was. I left that night, Bishop. If anything, my year in the temple taught me what Gautama figured out when he broke away from the holy men: if you want liberation, to be free, you got to get there on your own. All the texts and teachers are just tools. If you want to be free, you'resupposedto outgrow them."

"I'm sorry," I said.

"Don't feel sorry. There's no place anywhere for me. I seen that a long time ago. Wherever I go, I'm a nigger. Oh, and I been to mother Africa. Over there, where people looked like me, I didn't fit either. I don't belong to a tribe. To them I was an American, a black one, and that meant I didn't belong anywhere." He patted his pants and shirt, searching for his cigarettes. Having found the pack in his breast pocket, Smith lit one with a Zippo lighter, and blew a smoke ring my way. Then quietly he asked, "What about you? Do you feel at home --reallyat home -- anywhere?"

"No." I thought of my blundering pass earlier in the farmhouse. "I don't. Ever..."

"Then you're damned too," Smith said. "You got the mark. That's what I seen on you. Outcasts know each other. The blessed know us too, and keep their distance, and I can't say I blame 'em. We scare 'em. We make 'em uncomfortable. We're the unwanted, the ones always passed over. Until the day we die, we're drifters. Won't no place feel right for long. And that's okay. I accept that, Hell, I embrace it. My spirit don't ever have to be still. It don't need to sleep. Fuck that. The only thing is, I don't want to be forgotten. Not by the goddamn sheep. Or God. I want to do something to make Him remember this nigger --me-- for eternity."

Then Smith was quiet for a while, staring past me toward the lights of the farmhouse, and something in me quieted as well. He was a man without a home. Without a race. I pitied him and myself, for what he'd said about knowing no place on earth where he could find peace and security was something I'd often felt and feared, and perhaps that was even why I wanted -- or believed I wanted -- Amy. Now I feared it less, and for the first time since Chaym Smith surfaced during the Chicago riots, I understood the labyrinthal depths of his (our) suffering. Or did I? Hadn't he said all stories were lies? What, then, was I to make of the one he'd just told me? It had seduced me, but as always I didn't exactly know where truth ended and make-believe began with him.

"What will you do?" I asked. "Doc told us to help you -- "

"Help me, then." He got to his feet, brushing grass off the seat of his britches. "Best thing you and the girl can do is teach me what I don't know about Dr. King." His smile gleamed in the moonlight, followed by that maddening, ticlike wink. "Do that, and I'll take care of everything else."

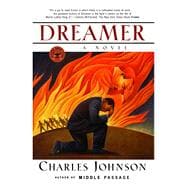

Copyright © 1998 by Charles Johnson

Excerpted from Dreamer by Charles Johnson

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.