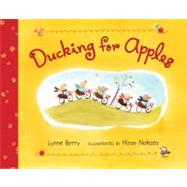

"This ducky picture book fits the bill.” --School Library Journal

“Nakata’s sweet, soft watercolors perfectly suit the cozy mood.” --Time Out New York Kids

“The cheerful ink-and-watercolor artwork is as fresh and amusing as the short, rhyming verse. Fine for fall storytimes.” --Booklist

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.