| Foreword | xi | ||||

|

|||||

| Acknowledgments | xvii | ||||

| Who's Who in Dugout Days | xix | ||||

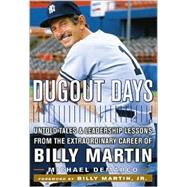

| About Billy Martin | xxix | ||||

| Introduction | 1 | (1) | |||

|

1 | (2) | |||

|

3 | (2) | |||

|

5 | (2) | |||

|

7 | (24) | |||

|

8 | (3) | |||

|

11 | (5) | |||

|

16 | (4) | |||

|

20 | (2) | |||

|

22 | (3) | |||

|

25 | (6) | |||

|

31 | (60) | |||

|

31 | (7) | |||

|

38 | (20) | |||

|

58 | (2) | |||

|

60 | (5) | |||

|

65 | (9) | |||

|

74 | (3) | |||

|

77 | (4) | |||

|

81 | (6) | |||

|

87 | (1) | |||

|

88 | (3) | |||

|

91 | (32) | |||

|

92 | (4) | |||

|

96 | (4) | |||

|

100 | (3) | |||

|

103 | (4) | |||

|

107 | (2) | |||

|

109 | (5) | |||

|

114 | (3) | |||

|

117 | (3) | |||

|

120 | (3) | |||

|

123 | (44) | |||

|

123 | (5) | |||

|

128 | (5) | |||

|

133 | (3) | |||

|

136 | (2) | |||

|

138 | (2) | |||

|

140 | (7) | |||

|

147 | (2) | |||

|

149 | (5) | |||

|

154 | (5) | |||

|

159 | (8) | |||

|

167 | (40) | |||

|

168 | (8) | |||

|

176 | (4) | |||

|

180 | (13) | |||

|

193 | (3) | |||

|

196 | (2) | |||

|

198 | (3) | |||

|

201 | (2) | |||

|

203 | (4) | |||

|

207 | (22) | |||

|

209 | (1) | |||

|

210 | (4) | |||

|

214 | (2) | |||

|

216 | (8) | |||

|

224 | (5) | |||

|

229 | (24) | |||

|

229 | (6) | |||

|

235 | (7) | |||

|

242 | (7) | |||

|

249 | (4) | |||

|

253 | (8) | |||

|

253 | (2) | |||

|

255 | (1) | |||

|

256 | (5) | |||

|

261 | (32) | |||

|

261 | (4) | |||

|

265 | (7) | |||

|

272 | (5) | |||

|

277 | (1) | |||

|

278 | (9) | |||

|

287 | (6) | |||

| Appendix: The Turnarounds of Billy Martin | 293 | (2) | |||

| Index | 295 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

Get to the Top

Billy-Style

"It was like the first or second day he was down on the field and he had this sense that he could see everything," Bill Kane, a longtime Yankee executive who knew Billy Martin for many years, once said. "If this was done or that was done, you could win a game. Move this way, one thing happened; move that way, another thing did. He said he just saw it all at once, all so clear."

Kane presents a picture of Billy Martin as a baseball wizard, eerie and awe-inspiring, a man with a unique second sight enabling him to perform in a way in which most of us can only dream about. There's Billy in the dugout, his wiry body perched on the dugout steps, his piercing eyes rapidly scanning majestic Yankee Stadium for opportunity, his face tight with concentration, his chin jutting out defiantly, his mind five steps ahead of the opposing manager. He is baseball's warrior general. He is in his element--a natural.

Make no mistake about it, by the time Billy Martin took over the Yankees as manager in 1975, he had a feel for baseball that enabled him to conduct a game from the dugout like a baton-wielding maestro. Just as Mozart seemed to magically write symphonies or George Soros magically guesses the direction of the financial markets, Billy just knew what was going to happen next on the diamond.

Of course, Billy as born manager ultimately rings false. As with other so-called naturals, a closer examination reveals years of dedicated training, study, and preparation that eventually enabled Billy to manage a ballgame with such finely honed skills and insight as to appear almost magical.

Billy's Early Life

Before studying Billy as a manager and leader, it's appropriate to take a quick look at the early years of his life to understand the qualities, influences, and experiences that shaped him. The young Billy Martin was a passionate, driven, optimistic person who slowly but surely achieved very ambitious goals against difficult odds. The young Billy Martin applied time-honored traits of hard work, desire, self-sacrifice, and commitment to make it in baseball. And the bottom line is that Billy Martin earned the equivalent of a baseball Ph.D. and became the leader that he did through a long education in which ideas were formed, evolved, and finally crystallized into a daring leadership style.

Most achievers achieve because they work for it. It's not luck, natural gifts, or better connections that generate sustained success. Sure, "breaks" happen from time to time. But hard work and dedication sustain long-term success. That's what Billy was all about from the time he was a little kid in Berkeley, California. Ultimately, Billy controlled baseball games from the top step of the Yankee dugout in the 1970s and 1980s as well as he did because of qualities he developed over a lifetime of true devotion to his craft, and not because of any mystical gifts from above.

Setting Goals

Billy Martin didn't play baseball just for fun or for gaining standing in his social group. Baseball captured his imagination fully. He loved the game, and from an early age, he instinctively sought to align his passion with his life, establishing the challenging goals of becoming a professional baseball player and a New York Yankee. According to boyhood friend Rube DeAlba, "He used to tell me all the time, 'Rube, I'm going to the Yankees.' This is in tenth grade. I'd tell him, 'Yeah, sure, Billy.' He'd say, 'You watch me, Ruben, I'm going to the Yankees.'"

Because Martin was small as a child and teen, and because he was not an extraordinary natural athlete, the odds were decidedly against him. Said Eddie Leishman, an Oakland area scout who initially passed on Billy for the minor league team he represented, "I liked him, but I didn't think he was strong enough. All I saw was a skinny kid who wanted to play. It didn't seem enough ... the big leagues? That's something else."

Billy had other disadvantages in life, including relative poverty compared with the nearby Berkeley college crowd, a lack of social status ensured by his West Berkeley residence, a large nose that garnered a lot of attention and teasing, and the knowledge that his father had walked out on his family before he was born. He lashed out at the teasing and his frustrations with a feistiness that he would brandish for his entire life. But when he learned to play ball--and excelled--he began to see self-worth in himself, and he began to gain positive recognition from others. Naturally, he wanted more, so that he could extinguish the insecurities his various adversities created inside. It would be a lifetime quest.

Paul Stoltz looks at adversities, such as those Billy faced, as:

"our defining moments. We are just beginning to understand the full impact of our childhood experiences upon our adult reality. Unfortunately, many children learn early lessons of hopelessness, which may be reinforced by their parents. teachers, relatives, friends, or anyone significant in their lives. Some get dealt even monstrous adversity that they somehow overcome. Once this authentic empowerment is unearthed and confirmed with a couple or more experiences, these individuals become bulletproof against adversity. They become immunized against helplessness. Many of the great athletes and leaders have stories of overcoming adversity. I have yet to hear of or meet someone people consider great who has not faced and overcome significant adversity along the way. As the saying goes, 'It is in the flames of adversity that our character is forged.'"

Billy certainly faced adversity when he was young, but through baseball, he found a way to fortify himself against the harsh world, and he found something he truly loved. Going to the Yankees was his own self-established measurement for success, and Billy pursued his goal with heart, soul, and vision--regardless of the skeptics--because his motive was genuine. Billy once told sportswriter Maury Allen, "I just knew I could do it ... I didn't care what other people said. I think you can do anything you want to if you care enough." Billy cared enough, and it helped to empower him.

* Phil Pepe: If there was a chip on his shoulder, it was put there by the fact that people kept telling him he was too small to play professional baseball. He wasn't good enough. He wasn't big enough. He couldn't make it. He couldn't do this. He couldn't do that. And that made him more determined to disprove that. He had such a drive to prove them wrong, a drive to succeed. He just overachieved constantly. I'm not a psychologist, but I think a psychologist would probably tell you that it's all the result of his upbringing, coming from the other side of the tracks, so to speak. No money. Poverty. He fought all the time as a kid .

* Charlie Silvera: He was a sort of deprived kid. He grew up during the war in the gang area around Berkeley. He had a tough bringing up, but he hung around the Oakland ballpark with Red Adams, who was the trainer there, and Red helped formulate Billy. He sure had to take a lot of abuse, because he had that big nose before he got it fixed. He took a lot of kidding, but he wouldn't back down. He had to fight, because he was a funny looking little guy. He had to be competitive. He was smaller, and he had to do a lot of little things that a bigger guy didn't have to do. But he was tough, and he wanted to succeed .

Dedication to the Game

Billy's words often echo those of the late Dr. Norman Vincent Peale, the well-known religious leader and positive thinker. Peale wrote in his classic book The Power of Positive Thinking , "A major key to success in this life, to attaining that which you deeply desire, is to be completely released and throw all there is of yourself into your job or any project in which you are engaged ... Hold nothing back." As anyone who ever saw Billy Martin on a baseball field can very well tell you, Billy never held anything back. He was totally dedicated and gave everything he had in life to the game.

* Gil McDougald: Billy all the time was thinking about baseball, because baseball was his love. That's it. I mean, I could never say I was in love with baseball. Baseball to me was a game, that's strictly all it was. To Billy, it was more than a game. It was his life. He loved it. It was like he worshiped the game .

* Jackie Moore: It was his life. It was his marriage. It was everything to Billy. Baseball was religion to Billy. He lived and breathed it, talked about it. His love. There was no misunderstanding at all that baseball was his life. He just loved it. He loved every aspect about it. He couldn't wait to win this ballgame today, then get in to play the one tomorrow. The different excitement, the different strategy, it would bring a different challenge to him. He loved to compete .

Billy's passion is memorable to his friends because it was so sincere, and it fueled his success. Many of us establish goals for the wrong reasons--money, parental approval, peer approval, and so on. But our goals must be meaningful to us, and must be aimed at providing us with real fulfillment, if they are to have value for us. It was that way with Billy and baseball. As a kid, Billy instinctively placed his love for baseball over every other aspect of his life, and he dreamed of the Yankees not for the money that he could earn but for the fulfillment that it would bring him. He achieved his goals, and ultimately money followed his success.

The Importance of Mentors

Billy played ball every chance he could, and in addition, he took full advantage of a perk that growing up in California allowed him--the exposure to several neighborhood big leaguers home for the winter, most notably Augie Galan. Galan, friendly with Billy's brother Tudo, took an interest in the undersized, overly ambitious kid, and gave him a unique tutorial few kids had. In essence, he became Billy's mentor.

* Phil Pepe: Did you ever see the piece I did for The New York Daily News Magazine on going back with Billy to his old neighborhood? It was very interesting to see his old neighborhood. It was a neighborhood where a lot of professional ballplayers had grown up. He talked about a guy by the name of Augie Galan, who was one of his heroes and role models. There were about a handful of players who played in the major leagues, who were older than Billy, who were neighborhood guys, and Billy kind of looked at them and wanted to be like them .

Billy was lucky to be surrounded by people who could teach him, but he also had the willingness to tirelessly pick their brains. And with the obvious love of the game that radiated from him, he had a magnetic pull on older guys who shared his passion. Across every field, energetic people who have "made the journey" often will go far out of their way to fan the flames in a youngster just getting started, especially one as eager as Billy.

According to Galan, Billy's first mentor, Billy "kind of took a shine to me ... he'd come over and carry my grip for me down to the park." Galan taught Billy baseball fundamentals on the one hand and mental strength on the other. Augie noted that, "I explained to him that ... if you have the determination nobody can stop you. I don't care how big you are, how small you are, what you look like, if you got it, you can make it ... I tried to insert that into him--just never give up, bear down all the time."

Augie encouraged in Billy traits he definitely possessed, and he encouraged him to follow his dreams. Billy recalled, "I was just getting into baseball and I was at an impressionable age when Augie was playing in the big leagues and I guess he influenced me as much as anyone. When he came home during the off-season, he would work with me and help me ... I admired Augie so much ..."

Later, after Billy made it to the minor leagues, many established baseball people came to admire his love of and dedication to the game--people like legendary managers Casey Stengel and Charlie Dressen and numerous ex-big leaguers such as Cookie Lavagetto and Ernie Lombardi. They also became mentors to the young Billy. In 1948, Stengel--managing Billy with the minor league Oakland Oaks--roomed the young player with ex-Dodger Lavagetto, who was just months removed from breaking up Yankee Bill Bevens's no-hitter in the ninth inning of the World Series. According to Cookie, "The first thing I noticed was how serious he was about the game ... He was a smart kid, even then, you could tell he was going far."

Like Galan before him, Lavagetto fanned the competitive drive already burning in Billy. Billy recalled, "I'll never forget what he said to me one night. He said, 'There are a lot of fellows in the minor leagues who have the ability to play in the majors, but they will never make it because they have no guts.'"

Martin had guts, and he was learning along each step of the way that the qualities that he did possess--smarts, courage, heart--could get him to his goal as much as raw physical skill. His mentors added fuel to his fire and gave him direction and opportunities. Billy took full advantage.

Of course, Stengel was the most important mentor to Billy. As previously mentioned, Stengel managed Martin with the minor league Oakland Oaks in 1948, just a year before he took over as manager of the Yankees. He came to love the brash, skinny kid as a winner and as a son.

* Charlie Silvera: I had met Billy right after the war when we used to go work out in the Oakland ballpark, Billy was always hanging around the Oakland ballpark there. He had a great teacher in Stengel. He emulated him. He was Casey's guy. He just wanted to win. He wanted to emulate Casey Stengel, and he picked up a lot of things from Casey Stengel. But he was Billy Martin .

Stengel had the clout to make things happen in Martin's career, and he did. Whatever weaknesses others saw in Martin, Stengel saw heart, guts, and a boisterousness that could help keep a team on its toes. In 1949, Stengel left Oakland for the New York Yankees, and in 1950, he called for Billy, not because he was a great ballplayer, but because he was a winning ballplayer.

* Gil McDougald: I tell ya, there were so many ballplayers that would have made it on any other ballclub, and been a real fine ballplayer, but they didn't play for our ballclub. But Billy was so aggressive in his own way, the way he played ball. Everything was from the heart with Billy. This is what he believed. He certainly believed he was the best ballplayer, that's for sure. He proved in certain situations like World Series time how valuable he was. And to see Billy do well in the World Series never surprised me, because he knew that he had the guts to challenge anybody. And what the hell, that's what it takes .

* Bobby Richardson: He wasn't as smooth as Jerry Coleman on the double play, but he played over Jerry because he'd knock the ball down, pick it up, and throw him out. He'd break up the double play. He'd do the things that would win the ballgame. So he in essence really was a winner. He was the guy that spurred all the others on. You know, you had a quiet [Phil] Rizzuto at shortstop, and you had Andy Carey at third base, who didn't say anything. But Billy was the one that would get on whoever it was. He'd give a little, "C'mon, run that ball out!" "Break up that double play!" "C'mon, we gotta go now!" And Stengel loved him--he was Stengel's type ballplayer .

* Charlie Silvera: Casey would prod him and say, "Go get 'em!" One night in the early '50s we were struggling. We were ahead in the standings, but we couldn't pull away, and it was later in the season. In Philly, Stengel says, "I'll give anybody $100 that gets hit with a pitched ball." Well, Billy got hit twice that night ... So he did little things like that. Anything to win .

Years later, coaches and players alike would come to understand the gratitude Billy felt toward his mentor Stengel for seeing something in him and giving him the chance to achieve his dreams.

* Jackie Moore: You didn't have to be around Billy Martin too long to listen to him talk about Casey. It was a father-son relationship, and there was just such a love there. And to hear him tell stories, I knew Billy well enough to know that Casey left some kind of impression on him. I could feel how Billy appreciated it, and I saw how he tried to carry that on and pass it on to his players .

* Charlie Manuel: He used to talk about Casey Stengel all the time, and his way of talking about Casey was how much he really respected him and liked him. He would say things sometimes about Casey sort of in a derogatory way, but at the same time, if you could listen to him, you got the feeling that Casey had a lot of influence on him and helped make him into the player that he was .

As much as Stengel loved Billy, he only used him in ways that were best for the team--an important lesson Billy would remember when he became a manager himself. Favorite or not, Billy played in only 34 games in 1950 and 51 games in 1951. Jerry Coleman started instead at second base. In 1952, with Coleman in the service, Billy became a semi-regular in Casey's platoon system, playing 107 games at second base as part of a three-man, two-position rotation. Gil McDougald played 38 games at second and another 117 at third, while Bobby Brown appeared in 24 at third base.

* Gil McDougald: When Billy came up, Casey said, "You're my second baseman with Jerry Coleman." And then Jerry went into the service. Then Casey's idea was, "I like the way Gil swings the bat, I want him to play. When there's a left-handed pitcher, Gil plays third, Billy'll play second. If there's a right-handed pitcher, Brownie'll play third, Gil'll play second." Billy was caught in between, but he played his part. He never moaned or groaned. It wouldn't have done him any good with Casey. And the guys on the ballclub wouldn't have enjoyed it, either .

Your boss and your coworkers don't want to hear you whine.

* Charlie Silvera: If you talk to the guys that played for Casey--and I did for eight years--Casey, he didn't care what you thought of him. He platooned [Hank] Bauer and [Gene] Woodling, and [Cliff] Mapes and [Johnny] Lindell, and [Bobby] Brown and Billy Johnson. And they'd say, "I'll show that crooked-legged bastard." And Casey knew that. You gotta be a bit of a prick in order to be a good manager. You can't let other people influence you. Casey would say, "You guys don't like me too much. Now, when you get your World Series check, you like me a little better." You talk to the guys then--"Jeez, he's unfair." But now you talk to a lot of guys that played for him--"He was a pretty smart old man, wasn't he?" But when you're in your 20s, you know every damned thing there is .

So at the same time that Martin benefited from the individual relationship that he had with Stengel, he also saw his mentor at work, mixing the talents of 25 Yankees to form a unit that won five consecutive World Series championships from 1949 to 1953. Like the other players, Billy played his role and saw the team win again and again and again. The Old Man was in charge, and when things were done his way, the team won. For Billy, Stengel was a great mentor who could both help Billy with his playing career and at the same time show him his future as a manager.

Learning about Winning

Most baseball fans know that Billy's fame as a player was earned as the second baseman for the great Yankee teams of the 1950s. Billy was part of Yankee championship teams in 1950, 1951, 1952, 1953, and 1956 that were all business on the field.

* Charlie Silvera: Thinking back now, when you went to the Yankees you had guys like Snuffy Stirnweiss, John Lindell, Tommy Henrich, and Billy Johnson, and the first thing they'd tell you when you got there, "OK, kid. You don't 'f--' with our money. We're here to win. We don't get 'em tomorrow, we get 'em today." And Billy understood, so later, when he got to play regularly, he was one of the guys who'd call a meeting and point fingers at some of the young kids and say, "Hey, you were out late, and here we're in a pennant drive. You guys better bear down, because we have to win it ."

* Gil McDougald: Let me tell ya, for the Yankees, I never heard one guy ever say, "Have fun." It was always, "Get serious, we gotta win the game." But you read this all the time, the players saying it. I gotta laugh, because it's not fun. It's not fun to make errors. It's not fun to strike out with the bases loaded. I don't think many guys on our ballclub ever thought in the terms "fun." After the game, it was fun. We won. But never on the ballfield did we ever go out and say "have fun ."

Billy thrived within this serious on-field environment. In 1952 and 1953, his clutch fielding and hitting were especially vital to the Yankee championships. In the 1952 World Series, for example, he made his famous catch of a two-out, windblown, bases-loaded pop-up off the bat of Jackie Robinson that would have cleared the bases and spelled disaster for the Yankees. Other players remember it to this day.

* Gil McDougald: Well, what happened was, Robinson hit the pop-up, and Jackie's a pull hitter. I'm playing deep at third, and the wind was blowing in and toward right field, coming across from third base to first base. So as soon as the ball went up, I started to run. And Billy was running. And Joe Collins was the closest to the ball, but he lost the ball because the sun field was on the right side of the diamond at that time. And Billy kept going, and when I reached the mound, I seen Billy coming. And Billy just made a helluva catch. He got there and just caught it at his knees. So how do you evaluate ballplayers? See, that was a real take-charge situation at that time, and Billy did the job. That's what saved the game and the Series. He showed he could perform under pressure. I tell ya, that was a helluva play .

And in the 1953 Series, Billy had 12 hits in 24 at-bats to take the Series MVP award. Opponents like Sam Mele, an outfielder for such teams as the Red Sox, Orioles, and Senators in the 1940s and 1950s, were well aware of what Billy brought to the table.

* Sam Mele: He knew the game. He knew how to win, he did things to win, and he did win. Made the big play when he had to make it, like that World Series pop fly. Or getting 12 hits in a Series one time. He did the things to help win the game. He'd steal a base, knock somebody on his ass breaking up a double play, and the next guy would get a base hit to win the game .

And whether it was Billy, Mickey Mantle, Yogi Berra, Gil McDougald, Whitey Ford, or Phil Rizzuto starring in any particular game, it was always a Yankee team effort. As a Yankee, Martin absorbed the culture of an organization committed to success. The Yankees played as a team and played to win. And because they did win, role players like Billy earned individual fame greater than that of many stars on losing teams. Players like Billy, Andy Carey, Bobby Brown, and Joe Collins are more famous today than many others from their era who had higher averages, more home runs, and fancier gloves, because they were Yankees, and they won.

* Bobby Richardson: I think my first reaction when I would just hear the name "Billy Martin" would be a member of those winning ballclubs when they won all those pennants in a row. I think he really valued the [Yankee] pinstripes. It was his life. He was the spark plug of that club. Encouraging, in his own way, the others to really go out and play together as a team .

Teamwork--for the true Yankees, the culture ran deep, well beyond shallow sloganism. When Mickey Mantle, the greatest Yankee of the era, was approaching death, he told his friends and the media how he wanted to be remembered--not as the greatest switch-hitter of all time or an All-American hero, but simply as "a great teammate." Said Billy, "It was the Yankee way of doing things, teammates helping teammates." The feelings of kinship Billy felt with his teammates, and the pride that the Yankee uniform awakened in him, formed a grip that never let up throughout his life. Billy gave his heart and soul to his teammates, even ones who might be playing ahead of him on a given day such as McDougald, Coleman, or Richardson.

* Gil McDougald: I think we were very close as a team. Casey liked the platoon system, and that you would think would have made it difficult. But it's a funny thing, when you're a ballplayer, especially when the game's on the line and you might be coming up, you like to hear the guy that is trying to win the same position that you play yelling, "Come on, Gil!" Well, Billy, I think, was the first one I'd listen to. Sure enough, he's rooting for you .

In fact, even when the Yankees traded Billy during the summer of 1957, he took the time to sit down with Richardson, his successor, to pass the torch like a true teammate. Richardson recalled the incident.

* Bobby Richardson: I remember very well when he was traded. We were in Kansas City and after the ballgame, we all got on our bus to go back to the hotel. And everybody was there except Casey Stengel and Billy Martin. And word sort of filtered through the bus that Casey and Billy were having a meeting inside and there was a possibility that Billy had been traded. And we waited for about an hour. I mean, it really took a long time. Finally, when he came out and got on the bus, he walked right to my seat and sat down by me. He said, "OK, kid, it's all yours now. I've been traded." And I'll never forget those words. He sat down by me and said, "OK, kid, it's all yours ."

Over time, Billy came to believe that what he brought to the table during his years with the team was a big reason why the Yankees were winning. Billy's five full seasons with the Yankees as a player--1950, 1951, 1952, 1953, and 1956--all resulted in World Series Championships. In 1954, Billy was in the service, and the Yankees did not make it to the World Series. In 1955, Billy spent most of the season in the service, returning to play the month of September and in the World Series; the Yankees did not win the Series. In 1957, Billy was traded to the Kansas City Athletics midseason, and the Yankees did not win the World Series. True, he was just a .257 career hitter. But he had a greater worth to the team than just reflected in his batting average.

* Phil Pepe: If you look at his record, the years that he was with the Yankees they won, and the years he wasn't with them, they lost. When he went into the service, they lost. The year they traded him, they lost. It always seemed that when he was around, they had a tendency to win. He would be the first to tell you that he was the reason, or one of the reasons .

As a player with the Yankees, Billy learned the lessons of winning--lessons he would pass on to his players when he became a manager.

The Devastation of Being Traded

A big factor in Martin's eventual managerial success came from the heartache he experienced in his 1957 trade from the Yankees to the Kansas City Athletics, and the erosion of his playing career from that day forward. As we have seen, as a true Yankee, Billy helped Bobby Richardson, his successor at second. But it took him years to recover from the shock and the hurt of the trade, and he didn't speak with his mentor Stengel for some eight years while his wounds healed.

Because his identity was that of Billy Martin, Yankee ballplayer--not just Billy Martin, winning ballplayer, or Billy Martin, hustling ballplayer--the trade was particularly devastating to him.

* Billy Martin, Jr.: As a player, from the day he left there, he was never the same. He never played with the same confidence and bravado that he did as a Yankee, and he became a journeyman after that, because in the back of his mind it crushed him. It hurt him so bad. "How could they get rid of me? After what I'd done for them?" I think it skewed his judgment. There's no doubt about it .

Paul Stoltz speaks of the goals we set as Mountains, and of the efforts we expend in Climbing our Mountains. Stoltz notes that our Mountains must be significant. He says of Billy's devastation at being traded, "This is a classic case of why it is so important that our Mountain be something greater than ourselves. It needs to be rooted in contribution, legacy, and a higher cause. Being a Yankee, while wildly ambitious, was a limited Mountain, like making money. Had I been Billy's friend, I would have asked, 'Why do you want to be a Yankee?' And I would have kept asking why until I unearthed the grander purpose for his life. This Mountain is not team dependent. If he had discovered that his drive was for 'helping other players play their best,' he could have Climbed that Mountain with undying passion until his final breath."

In a way, the trade was a blessing in disguise for Billy because, as a journeyman ballplayer on other teams, he was able to see, compare, and be part of several organizational styles that differed from the Yankee way he had accepted as his own. During stints with Kansas City, Detroit, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Milwaukee, and Minnesota, Martin played for nonchampionship-caliber squads.

His sad odyssey thus allowed Billy to observe and digest organizational differences between Yankee "winners," where as a role player he could be a star and a winner, and the second-division "losers," where he floundered without purpose.

* Sam Mele: I think he knew--being with the Yankees--what it took to win. And when he went to those other lesser clubs, he could say, "Hey, I should be doin' it the way we did it with New York." Because it was winning, winning, winning, and they all participated. I do my part, you do your part, and he does his part .

* Charlie Silvera: He knew what it was to win, and what it took to win. You had to give up yourself. You had to go the other way. When he got traded, he saw the other side of it. You find out what it is to lose .

Even worse than losing was the inevitable end of his career. In early 1962, the Twins released Billy as an active player. Sam Mele, the manager who had to let Billy go, played a significant role in launching Billy's own career as a manager by fighting to keep him in the Twins organization.

* Sam Mele: That spring, [team owner Calvin] Griffith wants to let him go, and I have to release him. Everybody's gone, and I'm sitting in the clubhouse with him, and we're both crying like two little kids--this is no kidding. We'd struck up such a great friendship. It'd started when he was with the Yankees and I was with Boston ... And I had to tell him he's released. But I said, "Damn it, I want you in the organization." And I talked to Calvin, I said, "He's got to be in the organization, Calvin." So they made him a scout .

(Continues...)

Copyright © 2001 Michael DeMarco. All rights reserved.