| Introduction | vii | ||||

|

|||||

| A Note on the Translation | xvii | ||||

| Overture | 3 | (2) | |||

|

5 | (40) | |||

|

45 | (60) | |||

|

105 | (30) | |||

|

135 | ||||

|

179 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

I have to admit that this injunction disconcerted me. To tell the truth, reader, I don't really like to be addressed directly at the beginning of a book. After all, why should I be interested in recommendations made by some unknown person, not to mention his private thoughts? On the contrary, what I like at the crucial moment of beginning, which is so full of solemnity that it ought finally to be recognized as having the sacred character that ancient religions, in their wisdom, granted it (and which is, moreover, so laden with promises that to do things right one should just begin again, over and over), is that I be treated with the proper discretion and that my preference (which is, I'm sure, shared by the majority of silent readers) for remaining incognito, invisible, be respected. I want to be able to come and go as I please, in full safety, without constantly running the risk of being harangued by some malicious watchman posted at the threshold to the domain into which, full of hope, I am preparing to make my entrance.

Nonetheless, I would have been inclined to overlook this initial awkwardness, to attribute it to some lack of delicacy (these days, you have to put up with that sort of thing if you want to continue to associate with people), had the content of the page itself not increased my uneasiness.

How should this kind of address be interpreted?

It could only be a joke. A wink, a little heavy-handed, toward a thundering Jarryesque outburst. Or perhaps, even more simply, a farce. Yes, as subtle, and in at least as good taste, as the old graffito that has delighted generations of schoolchildren. They hardly know how to write before it becomes their favorite thing to do. I can testify to this myself, for in certain neighborhoods in the suburb where I was born -- not necessarily the most impoverished (in those neighborhoods, nobody was interested in writing, even on walls) -- you saw it everywhere: inside buildings, hastily scribbled on the smooth walls of elevators or public toilets; outside, carved on the wooden fences around construction sites where the workers were on strike, or on the walls of buildings that were to be demolished. Every available surface was decorated with it. Amid the tediously repeated obscenities that explicitly exhibit, thanks to the convenience of anonymity, what our culture normally pretends not to know or tries to repress, one was sure to find it. Simultaneously a rallying cry for a few groups of outsiders and a vengeful manifesto exhaling wholesale anger, impatience, scorn. Sometimes ostentatious and provocative, with big, angular capital letters, sometimes written more cursively, discreetly and almost furtively, the message shone by its masculine concision: it was, largely inspired by the famous interjection (in four letters, just like the word `book') of a famous imperial general, an energetic, flat refusal addressed to anyone who reads it.

On the whole, I'm not opposed to jokes. I am even prepared to recognize, as people used to do, that laughter has a sacred value, and I cannot forget that amid the ruins of Sparta, one stela survived all the others, the one that was dedicated to the god of Laughter. Better yet: if from the whole of contemporary intellectual production in every genre only a dozen good jokes (the kind that make you laugh the hundredth time you hear them) were to remain, I should think our generation had not lived in vain. That shows how good an audience I am. So why shouldn't I pardon my author, who was no doubt carried away by a whiff of childhood or nostalgia, this regression toward bathroom humor?

But what about the prophetic tone? And the ironic or condescending allusions to my expectations, my illusions? And, to crown it all, the desire to intimidate me, relying on barely veiled threats? All of that constitutes an apparatus that doesn't seem to have been intended simply as a pretext for clowning around.

I thought I was pretty capable of recognizing a scribbler's whims and fancies, and had been for a long time. I was aware in particular of the importance (excessive, to be sure, but this is not the place to go into it) that some people lay on safeguarding their family's recipes, their club's gossip, their clique's teeny secrets, which they seek to conceal from common, profane eyes. I would therefore have acknowledged without difficulty that certain precautions might have been taken with regard to me, that I might be snubbed a little bit, and even that I might be scolded. But in all my experience as an avid reader, which is always conveniently present to my memory (and heavily, sometimes!) at the moment that I begin a new book, I could find no example of a such an abrupt reception. Before telling Nathaniel to dump the book , damn it, one could at least wait until he'd finished reading it!

However, I had read about these hussar-like attacks, these insolent approaches, these overtures as imperious as they were impertinent, to which we impenitent readers used to be regularly treated.

I also remembered some of the famous addresses to the reader that formerly constituted, at the beginning of works presenting themselves as difficult or innovative, so many warnings. `Timid soul, set your heels backward, not forward,' the anonymous author of the Chants de Maldoror once somewhat rudely advised. He was not the only one, nor even the first: another unknown author, a certain Alcofribas, long before ... Even in these cases, which have become more or less classic (since their scandalous nature, which was originally very striking, has with time become attenuated, as usual), the reader was always immediately provided with precise instructions, not to say threats, concerning the proper way of approaching the book. For one of these authors, the book was a box (or a bottle) that one had to learn how to open in order to grasp its precious contents; for the other, it was a bone that had to broken open in order to suck out its marrow.

This case was entirely different. The odd introductory remark looked very much like a prohibition. The exordium, instead of offering me brotherly guidance encouraging me not to give up too quickly when confronted by the difficulties to come, sought explicitly to exclude me, to exile me, in the most expeditious manner possible: I expected to be welcomed as a guest, and I found myself treated as an enemy. But the author, still more vicious than the ancient Barbarians who, bidding an ultimate farewell to the lands they had devastated, poisoned the springs and wells, chose to express his venom at the outset. In him, no trace of the kind of generosity that leads you to do the best you can in return. Like the cherub with the flaming sword who was to keep undesirables out of paradise, he thus established, between his work and me, an irremediable discontinuity. As if he wanted to perform all alone a ceremony to which he did not deem me worthy of being invited.

Perhaps the most unbearable thing about this guy was that he addressed me with such condescension (what right did he think he had to speak to me, right from the start, in such familiar terms?), as if I were a child. First of all, he reminded me, very inopportunely, of the time when my mother, worried (and no doubt secretly annoyed) to see me spending whole days confined to my room, staring into space, suggested -- with an insistence that irritated me without persuading me -- that I join my playmates outside in the sun and open air. Worse yet, he already claimed to know all my hopes and expectations and threw them in my face as if they were baseless dreams. Playing the prophet, he warned me against myself, acted as though he knew all the hidden corners of my mind and could read them as he would a book he had long ago deciphered.

Clearly, no one had ever treated me with such a mixture of arrogance and carelessness!

I refused (and who could blame me?) to pursue my reading any further.

`You ordered me to put this book down. Well, all right. I'm going to obey. Even better than you hoped. I'd be pretty stupid, after all, not to take you at your word.

`Do you have any idea how absurd you've been? Would you agree, except perhaps in the middle of some kind of nightmare, to hang around an artist's studio where you were allowed to enter and then immediately told to get out or close your eyes?

`To be sure, like those saints who are more eager for blame than praise, you are practicing an art of which I personally prefer to remain ignorant, the noble art of making enemies. Whom do you want to read you? God himself, maybe? Unless, like Baudelaire, you prefer to write for the dead ...

`However that may be, you should know that your expectations are a matter of indifference to me. So stay in the company you've chosen. And if you want your work to be a mere soliloquy, go right ahead!

`On that note, Mr. Cerberus, I bid you good evening!'

Now there , I said to myself with intense satisfaction while I was silently scolding the impertinent author, is a particularly dignified exit, and one not without a certain panache.

This boor probably imagined that he could push me around with impunity! By dismissing him myself, firmly and definitively, without a minute's hesitation, hadn't I succeeded in turning to my advantage a situation initially unfavorable to me, one that even threatened to become truly uncomfortable? Damn it, in literature these days, opportunities like that don't come along very often, especially for people like me, who are not much inclined to seek them out, so you have to know how to grab them when they come up.

And then, another consideration added to my satisfaction. It was connected with the inexhaustible tangle of memories that I usually try to keep dormant, but which my haranguer, in his thoughtlessness, had just stupidly awakened.

As I child, I learned that to be sure I always acted properly, all I had to do was to observe a few simple rules, which could be reduced to a very small number, at most a dozen, phrased in inalterable, lapidary formulas, austere in tone, piously transmitted in my family for many generations, and whose possession I considered a genuine talisman. They came straight out of the quietly ironic wisdom (itself ultimately optimistic) that all kinds of outsiders and minorities create to safeguard their image and to comfort their self-esteem, and they had quite naturally replaced the little treasury of nursery rhymes, proverbs, and maxims that up to then had helped get me out of all sorts of scrapes.

From both of these I had at least drawn a reassuring certainty: the world was not so terrible a thing as it appeared to be; one could, by using certain well-placed, well-chosen words, keep its most dangerous threats at a safe distance.

My experience as an adult had, of course, severely tested this ancient faith, without being able to destroy it (can one ever really destroy an edifice with such foundations?). In particular, I discovered the distance that separates the fine, harmonious, and rigid order that I had been taught to respect from the fleeting, unpredictable pulverulence of the reality I encountered every day. Therefore I was not sorry that I could still appeal, now and then, to one or another of these precious commandments.

There was one in particular, a genuine oracle, that had seemed to me worthy of the subtlest moralists, and which I kept in reserve, knowing that someday it would come to my aid and help me save face. That day had finally come. I was going to test immediately the pertinence and efficacity of my formula: If someone keeps me at a distance , I had often heard my mother say (for in the closed world in which we lived, there was no lack of opportunities to say it, or at least to think it), my consolation is that he keeps his distance too .

So without delay, I closed the volume: I'd had enough problems for that day.

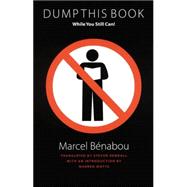

Excerpted from Dump This Book While You Still Can! by MARCEL BÉNABOU. Copyright © 1992 by Éditions Seghers, Paris.

Translation copyright © 2001 University of Nebraska Press. Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.