| Acknowledgements | xi | ||||

| Introduction | 1 | (2) | |||

|

3 | (138) | |||

|

141 | (14) | |||

|

155 | (156) | |||

| A Qat Glossary and Consumer's Guide | 311 | (5) | |||

| Bibliography | 316 | (2) | |||

| Index | 318 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

`perhaps all pleasure is relief'

William Burroughs, Junky

The first man I stopped was helpful.

`You want qat? What's that then -- drugs?'

There were two Pakistani ladies passing us, dressed in chunky cardies and silky shalwar; I scanned their faces anxiously, but there was no reaction.

`Well, sort of drugs -- yes, I suppose it might be ...'

He nodded. `You want drugs -- blow? I'll get you some blow. How much you want?'

`No, I don't want any blow.'

`Good stuff, mate, don't worry.'

`Look, I don't want blow, I want qat. It's a leaf from Ethiopia and Yemen. You chew it.'

His face clouded over into sullen disinterest. `Never heard of it. I do blow, that's all.'

He strolled away. The street was soon empty of people. On one side was a railway viaduct, a line that had once served London's docklands; on the other were some low-rise flats with beady-eyed little windows and security doors. It was possible of course that the qat-seller was in there, behind a dead-locked door with a spyhole and surveillance equipment, handing out little packets of happiness through an armoured grill. It was also possible that the local Yemeni greengrocer would have it, labelled salad, sitting between the red peppers and purple onions. Qat is nothing if not adaptable: should the President of the United States be caught holding state meetings the same way they do in Yemen and Somaliland, over a few bundles of qat leaves, he would get the same treatment as any crack addict. It's legal in Britain, banned in the USA, celebrated in Yemen, vilified in Saudi Arabia.

Unfortunately, I had no map for the qat-shop in the East End and the directions I'd been given were horribly vague: `a kind-of shop place, a room, it's his house, loads of people coming and going -- you'll find it', so I ended up loitering outside a café waiting for inspiration, accosting a second passer-by, a young West Indian who came from the café.

`Excuse me. Do you know where I can buy qat?'

`Drugs, right?'

`Well, sort of.'

`You want powder?'

`No, it's a leaf.'

`You want powder. Leaf's shit. Wait here.' He started to move away. `Just wait, right? One minute.'

`No, I want qat -- it's a leaf, green stuff -- and legal.'

He was already ten yards away, but he stopped. It was as though the dread word `legal' had let the air out of his trainers, a warrant card flashed in his face.

`Yeah, right, leaf.' He set off down a side street, slam-dunking a balled-up paper napkin over the fence.

I walked a few yards up the street and stopped, wondering what to try next. Then I noticed the door next to me was ajar, a red door of what I had taken to be an empty shop lot next to a bookie's. Peering inside I could make out one end of a chiller display cabinet of the sort that fishmongers use, only this one was stocked with bottles of mineral water and Coke cans. I put my hand on the door and eased it open a couple more inches. The rest of the display cabinet swung into view: a case of soft drinks and in the little white plastic trays where the filleted cod steaks should have been, piles of smooth green pods each about a foot long, carefully stacked in tidy pyramids of fifteen and looking like some alien seed stock on the brink of hatching out and invading the East End. I had never seen qat wrapped in banana leaves before but I knew I had found what I was looking for. With a push, I opened the door and stepped inside.

Qat, khat, chat, cat, jima, mira -- the London Institute for the Study of Drug Dependence issues a factsheet stating that it is a green leafy plant cultivated throughout eastern Africa and the Arabian peninsula, and containing two pharmacologically active ingredients, cathinone and cathine, the effects of which are something like amphetamine sulphate. `The khat plant is not controlled under UK domestic law,' the factsheet says. However, `Cathinone and cathine ... are controlled under the United Nations' Convention on Psychotropic Substances.' In the United States, Canada, Switzerland, Scandinavia and most of the Middle East, excluding Yemen, the leaf itself is banned. In a lecture given at a UN conference in 1983 it was stated that cathinone, the main active constituent, could `create the same problem as cocaine if it was available'. Only twelve years later, in Manchester, a smiling young nightclubber held out his hand and showed me the tablets of cathinone that would make him dance all night and never lose that smile. In his pocket were some thin stems of Kenyan qat which he stripped and ate one-handed with the same skill as a Somali gunman clutching a Kalashnikov: the Ecstasy generation was branching out. No quiet room with a view, no water-pipe gently bubbling, no contemplation or poems or fine words, not even a closed door and a carpet to sit on. I wanted to press my hands to my ears and shout: `Stop! This can't be right!'

As an eight-year-old at primary school I remember being handed a strip of paper and told to twist it once and stick the ends together. When I ran my finger along one side I can still recall my amazed discovery that there was no edge, no end, my finger just kept going on and on. Qat does that: challenges the borders and boundaries. It is legal and illegal, safe and unsafe, addictive and non-addictive, it makes you dance all night, it makes you sit and stare, it moves you to hallucinate or has no effect at all -- it all depends on where you are and who you are talking to. In the USA, where it is demonised along with all the other substances, it also grows as an ornamental tree in various botanical parks and gardens. Occasionally, mysterious `prunings' occur, much to the bafflement of gardeners and park-keepers. It is a substance that an initiate can quite calmly sit and chew while calling for it to be banned. Qat sits on the fence of our preconceived ideas and on either side of it too, challenging our conceptions of what a drug is, of what addiction is, of what an addicted society should be like. It questions where we draw the limits and makes those limits look as ridiculous as those straight-line colonial borders on maps of Africa.

As to its effects, the Institute's bulletin declares: `In cultures where its use is indigenous, khat has traditionally been used socially, much like coffee in western culture.'

When I first read that bland, easy statement, I laughed: here was a leaf that in Yemen has a pivotal role in poetry, music, architecture, family relations, wedding and funerary rites, home furnishings, clothes, what people eat, when restaurants open and close, where roads go to and where not, who owns a car and who does not, office hours, television schedules, even whether couples have sex and how long it lasts. At a conservative estimate, it accounts for one third of the gross national product, politicians take decisons on it, businessmen strike deals over it, even Texan oil men will force themselves to accept bouquets of it, `exchanging green gold for black gold', one of them told me; from the centre of the capital to the outermost desert reaches, tribesmen will accept judgements made by men with qat in their cheek. It had consumed my money, decided my friends, chosen my house, taught me some Arabic, and given me a love for the country more powerful than for my own, and all of that, this all-pervasive substance, was to be neatly summarised `much like coffee in western cultures'.

In his backroom qat-shop in London's East End, Haj Ali had tried to evoke a little of his homeland. Along the right-hand wall were propped hard cushions to rest the qat-eater's back, the cloth a rich maroon velvet with lacy antimacassars draped along the tops. For seating there was a long thin cotton-stuffed mattress overlaid with oriental rugs. Elbows could slouch upon simple square bolsters, also in maroon velvet, and to supplement these were softer slip cushions with lace-edged cotton covers. If this was the Orient, the opium den of the dreamy east, then it was based on a sketch by Queen Victoria.

One man in a gold-embroidered skullcap was sitting on the mattress, two others were standing in front of the chiller examining the qat. As I came in they all looked up and frowned, not in an unfriendly fashion, just puzzled at the intrusion. They did not speak, so I greeted them, going over to shake hands with the seated man first as he was oldest and obviously the owner.

`As-salaam aleikum.'

The instant they heard Arabic, their faces relaxed. The old man smiled. `Wa aleikum as-salaam. You speak Arabic? And you know qat?' He got up and went behind the chiller to select some bundles for me. `How many do you want?'

`There are two of us. Don't you have Yemeni qat?'

`No, this is all from Harar in Ethiopia.'

He passed across a bundle and I inspected it. The smooth green wrapping was a banana leaf tied with a thin strip of dry raffia. At the top it tapered to a point, at the base it was open, revealing the cut ends of about twenty stalks. I made a show of looking at these although they appeared to be exactly the same as all the others in the display: red-barked with a dirty white pith.

`It's not fresh,' he apologised, `Not like you buy in San'a -- but then it takes two days to get here.'

The two other customers interrupted our conversation to take their leave. `We've got three bundles.' One of them searched through his pockets for money while Haj Ali waved at him, protesting: `No, no, no. Next time -- no problem.'

But the customer found his cash and a brief battle ensued which the shopkeeper won, successfully repulsing the customer's attempt to pay. When they had gone I asked Haj Ali if he had ever visited Harar.

`Yes, many years ago. It is an Arab town in the hills of Ethiopia and they grow the best qat. Some people say that the tree came from there and was taken to Yemen.' He took the qat from me and put it with another bundle in a white plastic bag. `We used to trade there and up to Djibouti, Eritrea and Sudan.'

`Was it an old route?'

`Yes, for taking slaves from Africa to Arabia. They would come down from Harar to the coast at Zeila, which is now very small. Then they would cross the Red Sea by dhow to Mokha -- you know Mokha? Famous for coffee? -- or Aden. These were the old routes: when I was a young man we used them.'

I knew that the same Aden-Zeila-Harar route was that taken by the explorer Richard Burton in 1854-55, when he became the first European to see Harar and live -- non-Muslims having been barred from the holy city on pain of death.

`And qat came from Harar?'

`This qat? Yes.' He handed me the white bag.

`But originally -- the first qat?'

He shook his head. `They say Sheikh Shadhili took it from Harar to Mokha because the people wanted something to keep them awake. But who knows -- that is more than five hundred years ago.'

He shuffled towards the cushions by the wall, indicating that I should sit down too. But at that moment a large party of customers, a group of Ethiopians, arrived and he was distracted. I tried to get one last question across as more men came inside and the room filled with voices and different languages.

`Is it still possible -- I mean, the old route? Do the dhows still go from Zeila or Djibouti?'

He was loading another white carrier bag from the chiller, holding up another conversation with the large group. `How many? Six? You British were in Aden then. We'd go across to Somaliland or down the coast to Zanzibar and Tanganyika then back to Aden.'

`By boat?'

`By boat -- sambuk -- or plane. They took Harari qat to Aden in those days by plane -- that was how the Ethiopian Airlines started. The British were always fighting with the Imam in the north of Yemen, you see, so the qat camels were often held up.'

`But what about now -- is it possible now?'

He shrugged. A fellow Yemeni had come in and the conversation had switched to Arabic: mine was rusty after two years of neglect, but his answer was clear enough.

`As-sambuk? Ma'arifsh. I don't know.'

More customers arrived, a group of Somali men and an Ethiopian, so I paid for the qat and said goodbye, passing through the doorway from the warmth of Yemen into the grimy grey autumn of London.

Haj Ali had not been wrong in suggesting Harar as a possible origin for the qat tree. Many sources give dates for the substance being sent to Yemen from Harar: brought by Ethiopians between 1301 and 1349, brought to the Yemeni city of Ta'izz in 1222, taken by a sufi named Sheikh Shadhili (there were a few by that name) in 1429 -- but there was nothing definite, no precise documentary evidence. Although qat is mentioned by savants and sufis like al-Miswari of Ta'izz in the thirteenth century, they might have been referring to the tea made from the leaves of qat, rather than the plant -- an explanation for the absence of the tree in the plant register drawn up for the King of Yemen in about 1271 and also for the great traveller Ibn Battuta failing to spot it in 1330. Quite when this strange leaf started on its long journey from innocuous and unnoticed tree to cultural mainstay is a mystery but it seems likely that religious men first discovered its properties, using it to ward off sleep during long, night-time meditations, and carrying this useful spiritual helpmate with them on missionary journeys. The cultural beginnings of qat would have been born out of travel and movement just as Napoleon's expedition to Egypt brought hashish to Europe and nineteenth-century Bayer company salesmen had taken a marvellous new cough remedy called heroin across to the USA.

The distance covered by qat on that first movement was not so great but the route from Harar to the coast has always been fraught with difficulties. When Richard Burton went back down that road in January 1855 after just ten days in Harar, heartily relieved to have survived the Emir's uncertain hospitality, he was attacked and took a spear-thrust through his cheek. He was fortunate to survive with only the savage mark you can see in Leighton's painting of him in the National Portrait Gallery.

The other great literary figure of the nineteenth century associated with Harar fared worse. Arthur Rimbaud, poetic prodigy, retired at twenty with the valedictory A Season in Hell in which he wrote: `My day is done; I am leaving Europe ... I shall return with limbs of iron, dark skin, a furious eye: from my mask, I shall be judged as belonging to a mighty race.' But in reality he returned physically shattered and died in Marseilles soon after.

North of Harar, towards the French-speaking enclave of Djibouti, lies a region of Africa about which few good words have been said. Early travellers found the people had the disagreeable habit of slicing off testicles as trophies. The average temperatures, day and night, summer or winter, are the highest in the world. When I thought of qat being carried east across this volatile wilderness, I thought of the tins of Golden Syrup that fill the shelves of San'a's grocery shops and the picture of a dead lion above the Biblical quotation: `Out of the strong shall come forth sweetness.'

I took my bundles off to Hackney, where I sat with Khaled, a Yemeni friend, in the garret window of my sister's flat overlooking the railway, slipping the little leaves and shoots past our lips while Khaled said, `Isn't it wonderful to sit together again like this? I'm in San'a now, really, at Muthana's place -- the best place to take qat. This room reminds me of San'a somehow.'

This was not entirely by accident. I had pulled all the cushions onto the floor, hidden the sofa on the landing, swathed parts of a vegetable rack in stripy ethnic rugs to make armrests, and covered everything in yards of the bright scarlet and blue Indian cloth that San'a ladies use as shawls. But not only that, the room had two garret windows set down long dormers and these channelled the light into twin columns of dusty gold. By sitting on the floor we could no longer see the grim viaduct curling away from Hackney Central station, only the sky and this golden light pouring in. And if the gold had more to do with the reflections off the garish tandoori house opposite, then it only added to the eastern flavour. Khaled had brought his lute which he began to strum: his high plaintive voice gaining in confidence as be played, the sound of it hauntingly sad yet nailed to the driving beat of his right hand on the strings. Then I could see myself in a shared taxi on the road to San'a from the south, qat in lap, whacking the dust from a cassette tape before putting it in the machine and listening to that same bitter-sweet sound as the landscape of distant tawny mountains rolled by in slow motion.

My first experience of a Yemeni qat session was in a beautiful old Jewish house in the Al-Qaa quarter of San'a. There were alabaster windows threading the sunlight into amber ribbons, cushions covered in rich fabrics, the gentle curl of the hookah hose across the floor and conversations fascinating and varied. Through the open door was a sunny courtyard where trellised vines grew above a fountain and pool. This was the type of house that Jamal al-Din al-Shahari wrote about in 1747 in his book that glorified San'a as `the City of Divine and Earthly Joy'. Like the poet, we chewed qat that was well chosen, washed and gleaming, the shoots were both supple and crisp. And I hated it.

For an hour or two it was pleasant to relax and talk, though there was obviously nothing to be gained from these bitter leaves. After five hours I never wanted to see it again. Like many other outsiders, I was waiting for the drug to happen and it didn't.

Then one night around Christmas-time a few months later, there was a knock at my door. It was past midnight and I went down in some irritation to find a strange figure in gentleman's walking brogues, twill trousers and what appeared to be a coat made from a bedouin tent. He was carrying a knobkerrie which he waggled at the street dogs. It was Tim, a colleague at the school where I was teaching and a long-time San'a resident.

`They really are beautiful animals, aren't they?' he said as the hounds formed a snarling semi-circle around us and the door. `But probably rabid.'

We went inside and he explained the reason for his visit: `I wondered if you would like to come round tomorrow? I'll be having qat, but you don't have to. There's this high room on top of my house -- the seventh floor -- it has a wonderful view over the Old City and you could photograph it.'

My first experience was still fresh in my mind and I muttered something uncharitable about `expensive placebos' but agreed.

Tim's house was a magnificent tower, daubed with zig-zags of whitewash and entered via a stout castle door that had sunk two steps below street level as the centuries of dust piled up. I climbed the stairs to the roof, then up again on a narrow stone staircase to an extra little room that seemed to float over the surrounding houses, a place that could seat only four in comfort with tall arched windows of stained glass and a hand grenade that held a cigarette lighter. I took my photographs and Tim and two Yemeni friends talked about Yemen, about a lost city on top of an unclimbable crag that Tim had tried to reach, about one-legged poets and a place where wild tribes still traded in large silver coins stamped with the image of Empress Maria Theresa of Austria. I didn't buy any qat and I did not accept any from the others, but it was on that day that I became an addict because I began to understand that the pleasure of a qat session was not really about qat at all, but about the companionship of the sessions in cave-like rooms floating high above the ancient city.

Khaled understood this immediately when I told him about it. `I have not had qat for eight months,' he told me. `Who would I sit with? And where?'

He came from a remote area in northern Yemen, a place famed for its fiercely traditional tribal law. When he had first won his scholarship to study translation, I had worried that he would find London an appalling sewer of dissolution and moral decay without even basic civilising amenities such as a proper qat market. But when I suggested as much, he recoiled in amazement.

`You think that? No, believe me, London is a paradise. As for qat I can manage without it. Qat is an evil thing, it would be better if it was banned.'

So saying, he sighed and selected another sappy little sprig from the plastic bag. But I was less than enthusiastic about London myself: I had spent ten years abroad, before returning in 1994. Now I was pining for Yemen.

Khaled gave me short shrift on that score. `I'd stay here forever if I could. Let me give you an example: in our area if someone kills another man from another tribe, then those people can come and kill me in revenge, even though I had nothing to do with the murder.' I had a vision of a tribesman armed with a matchlock rifle, face weathered by desert winds, sauntering up Hackney High Street in search of vengeance, a Yemeni Clint Eastwood.

Determined that I should not take such a rosy view of his country and such a dim one of my own, Khaled pressed his case.

(Continues...)

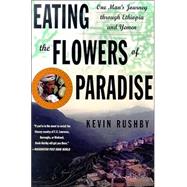

Excerpted from Eating the Flowers of Paradise by Kevin Rushby. Copyright © 1999 by Kevin Rushby. Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.