The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

Lee spots the package just as she turns into her driveway. She leaves the car running, the door open, the ignition pinging. She leaves the toilet paper and two percent milk, the previously frozen shrimp, the half gallon of Heath Bar Crunch, the mesclun mix, and four not-yet-ripe tomatoes imported from Holland on the baking vinyl seat. It's late March. After three weeks of rain and one freak snowstorm, the sun blazes. And there, slumping against her front step in its quilted manila sack, lies Lee's actual, palpable, three-dimensional book.

The first thing she notices: Book Rate Magic Markered all over it with a dollar's worth of last year's stamps patched along the top. And a postage-due Post-it, whose penciled-in four cents has been crossed out and signed I paid, Pete Goodreau, mail carrier. Shouldn't such a package have sped from the printer's in a brown UPS or white, orange, and purple FedEx chariot? Shouldn't it have flown in on the wings of a full-bodied jet? Not seven-days book rate with four cents owed. She shudders. What if Pete Goodreau hadn't anted up the pennies? What if the package had been tossed into the bushes? What if the cleaning lady had shoved it in the coal scuttle beneath four seasons of L. L. Bean catalogues? What if, what if could be the motto for her whole life. She stops herself.

She picks it up. It's the size of one of those journals of American history that Ben seems to receive on the hour. Log a Rhythms: New England Lumber Industry Quarterly, The Thoreauvian Society Bulletin, Past Perfect Newsletter in Ethnography, Acadia Review are all stacked on the table in the front hall. Hundreds of pages of dense print and inserted sheaves of maps. In contrast, her own package is light. But then again she didn't expect a tome.

She opens the door, kicks away the letters paving the floor behind it. She spies an envelope in Johnny's handwriting with Photos: Don't Bend and a margin of Japanese characters trellised up one side. Her heart lifts.

But first she goes back to the car, turns it off, unloads the groceries. In the kitchen she puts everything away. She runs water into the kettle, changes her mind and pours it out. Inside the refrigerator door stands a corked half-empty bottle of Vernaccia that she and Ben opened last night to mask the rubbery linguini. After a sip, Ben had set down his glass. "I'm pooped," he sighed. "I don't know when I've been so wiped out." And pleading an early class had gone to bed before nine. Lee had finished his wine and two more glasses, then stayed up until midnight flicking the remote between a panel of critics on Book TV and a rerun of Brief Encounter on the Movie Channel. When, at last, Celia Johnson forsook Trevor Howard to return to her husband, Lee staggered up the stairs, eyes filled, nose stuffed as if this had been the first time, not the thirty-first, in which she had witnessed these lovers part. In bed, Ben was snoring. He'd pulled all the covers over to his side; one hand was draped on her pillow; one foot stretched across her nightgown folded on the mattress's edge. His toenails needed clipping.

Now, upstairs she hears Ben pacing. His classes were over at noon today and he's back working on Nathaniel. Ever since he discovered, more than fifteen years ago, a few diary pages in the Hannibal Hamlin College Library written in Nathaniel Tarbell's idiosyncratic hand, this hitherto unknown chronicler of Maine's logging industry has become as much a part of the Emery household as the message board on the back door and the wind chimes on the front porch. Nathaniel, they all call him, as if in minutes he's going to show up to eat the meat loaf or take the garbage out. "So what's Nathaniel doing now, Dad?" Timmy might ask. His position is monitored the way you'd chart an invading army's progress across a mock-up battlefield. Is he on a boat, under a bridge, taking tea in Mrs. Higgins's front parlor? "Cut those bangs," she once ordered Maggie. "When Nathaniel trims his sideburns" was Maggie's reply. No wonder Ben's sermons on the evils of processed food yield no converts; the children are convinced that Cap'n Crunch is banned from their own table only because it has never filled Nathaniel's breakfast bowls.

In a month, Ben has to deliver a paper on Nathaniel's view of labor-management relations in the Allagash to the Organization of American Historians' annual conference. This year it's in Chicago. He doesn't want to go. He hates to travel; he's leaving home only for Nathaniel's sake. He could have walked to Chicago, the miles he's put in on her mother's Bokhara tribal rug. The pile is worn flat where he stalks the same twelve feet. Grooves like a two-lane highway run down the middle where he rides his desk chair's wheels up to his computer; she knows the exact spot in the wall where he lobs the crumpled balls of prose that fail to capture Nathaniel's Yankee eccentricity. Is he mimicking frustrated-writer scenes from Hollywood biopics? In her own literary struggles, she's never been tempted to pulverize a page of acid-free rag. But she supposes crunching typescript is physically more satisfying than blackening paragraphs and hitting delete.

Should she call him down to see her book, this fledgling whose birth took longer, was tougher than anything merely obstetrical? She can just picture his delight. The fuss he'll make. She starts for the staircase. She stops. Perhaps she'll wait. First, she might interrupt a brilliant sentence or dam a flowing paragraph. Second, well—she has no more excuses for forbidding him to read a not-there-yet draft; now it's a book, he'll read it—she wants him to—though some of it might be hard for him. Still, maybe she flatters herself, this was . . .

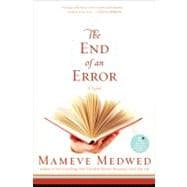

The End of an Error. Copyright © by Mameve Medwed. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved. Available now wherever books are sold.

Excerpted from The End of an Error by Mameve Medwed

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.