The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Introduction: It’s Time to Be Mad As Hell

On November 17, 2005, Congressman Jack Murtha (D-PA) stood before the House of Representatives and startled the nation by saying out loud what many of us had been thinking: It was time to bring our troops home from Iraq. “The U.S. cannot accomplish anything further in Iraq militarily,” he said. “It is time to bring them home... It’s a flawed policy wrapped in illusion. It’s time for a change of direction. My plan calls for immediate redeployment of U.S. troops consistent with the safety of U.S. forces. The American public is way ahead of the members of Congress.”

Today this statement wouldn’t be news at all. Almost all Democrats and many Republicans consider the war a catastrophe. But when Murtha stood up and made this statement, that was not the case. It was not at all politically correct for a politician to proclaim that our troops should come home from Iraq, and it was all the more astonishing and courageous coming from Jack Murtha. Murtha had served in the Marines for thirty-seven years and in 2005 was the ranking Democrat on the House Appropriations subcommittee that oversees military spending. Jack was the most consistent and staunch supporter of the military in Congress -- and now he had decided that President Bush’s Iraq policy had failed and it was time to start withdrawing our troops.

The Republicans were irate. Almost universally they had supported the Bush war policy. Several Republican members immediately issued statements denouncing Murtha, calling him a coward. Freshman Ohio conservative Jean Schmidt, then just two months into her first term, said smugly on the floor, “Cowards cut and run. Marines never do.” Democrats responded with boos and later she was forced to apologize.

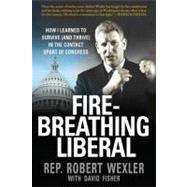

In my office, Murtha’s statement generated quite a stir. I’m Robert Wexler and I’m a proud liberal Democratic member of the United States House of Representatives. I’ve represented Florida’s 19th Congressional district on the southeast coast for six terms. Like Murtha and most of my colleagues, I’d voted to give President Bush the power he needed to launch an attack on Iraq. It was the worst vote of my career. Within months I’d realized that the nation had been manipulated by faulty intelligence and selective briefings, and it was a vote I had come to regret tremendously. But I’d voted that way. Since that time I’d been strongly critical of how the war was being waged. And now Jack Murtha, a highly respected and hawkish Member serving his sixteenth term, had challenged the rest of us to end it.

Murtha’s statement initiated an intense debate in my office. Initially, my chief of staff, Eric Johnson, felt that having voted for the war, we had a special obligation to see it through and said flatly, “We’re not supporting the withdrawal in six months.”

My office is loosely run, so much so that when we recently hired a new employee and he asked about the office rules, the others all looked at one another, waiting for someone else to tell him there were none. And no member of my staff is shy about disagreeing with me- - or with anyone else. I’m extremely fortunate: I have a very intelligent, dedicated and committed staff. In fact, the documentarian Ivy Meeropol produced and directed a six-part series titledThe Hillfor the Sundance Channel focusing on my staff and the way Congress works. One reviewer commented that in dealing with my staff I resembled “a beleaguered camp counselor.”

Among the members of my staff was Halie Soifer, my legislative assistant. Halie is idealistic and passionate, and especially knowledgeable about foreign policy. And like all members of my staff she isn’t afraid to speak up. She was quick to disagree with Eric’s assessment. “Maybe we should,” she said. “It’s sound policy.”

I appreciate the views of my staff, but I hadn’t reached a conclusion. And in the end itismy decision. While I desperately wanted to end the war and get our troops out of Iraq, I wasn’t certain that an immediate withdrawal was practical, possible, or desirable. Going into Iraq had turned out to be a colossal mistake, but I didn’t want to compound this error with anything but the most thoughtful withdrawal plan. Obviously it takes considerable time to safely and responsibly redeploy or withdraw 150,000 troops. I wondered aloud, “I guess my reaction to it is, Do you dislike George Bush so much that you jeopardize the stability of the entire region?”

Halie responded, “The question is, Is our being there doing anything to ensure the stability of the region? Murtha is actually saying our leaving will empower the Iraqi soldiers to step up to the plate.”

Eric Johnson has been at my side for eleven years. We’d met almost two decades earlier, when I was twenty-eight years old and running for the Florida Senate while nineteen-year-old Eric was running for the school board. Eric still looks like he’s nineteen years old -- even though he and his partner, James, now own a house and have an adorable adopted son. Eventually Eric became my chief of staff, which means he is essentially my alter ego. He is in charge of every task from running the office to helping shape policy. And as is often the case, Eric was disgusted. “The administration didn’t have a good plan going into the war; they don’t have a plan to get out of the war. To impose one means we have a half-assed exit, too.”

“People are dying,” Halie said.

“People can die on the way out, too, if it’s sloppy or screwed up,” Eric responded.

I wanted the troops out as rapidly as possible, but I also wanted to consider all the consequences. “Okay,” I said. “Let’s say you withdraw, let’s say you avoid massive American casualties on the way out, but let’s say you destabilize Egypt, you break up Iraq into three parts, you almost guarantee the instability of the region by withdrawing. What about the credibility of America?”

Halie scored the final points -- and stopped us all in our tracks. “Where is our credibility now?” she asked.

Where indeed? Every month we were losing more than 100 soldiers, in addition to the many hundreds more suffering life-altering injuries, and we were spending almost $5.5 billion. There was no long range-plan, and no end in sight. Worse, our reputation and credibility in the world were in tatters. It was obvious to me that a dramatic change was needed. But was Murtha’s approach the right change?

We spent most of the afternoon discussing how to respond to Murtha’s statement. We considered issuing a press release in which I would announce my support for Murtha’s call for withdrawal, but also my belief that it should be completed in phases. And then I would denounce the disgusting Republican attacks on Murtha.

This did not appear to be an issue on which I would have to vote. With Republicans in control of the House, it didn’t seem possible Murtha’s proposal was ever going to be brought to the floor. At least that’s the way it appeared until the Republicans decided to use the war for political gain.

Republicans saw this as an opportunity to brand Democrats as traitors. California conservative Duncan Hunter, the chairman of the Armed Services Committee, introduced a Resolution urging “that the deployment of the United States forces in Iraq be terminated immediately.” The Republican leadership intended to bring that Resolution to the floor and force Democrats to vote on it.

Hunter told reporters, “I hope the message that goes back to our troops in Iraq is that we do not support a precipitous pullout.”

Normally, legislation is introduced and first heard and debated in a committee. Only after a laborious process of testimony, amendments, and voting does legislation come to the full House for consideration. But this resolution was being treated very differently. It was going directly to the floor. Eva Dominguez, my senior legislative assistant, was furious. “How could they bring it to the floor without even going to a committee?”

Halie had the answer. “They can do whatever they want. They’re writing the rules as we speak. It’s a dictatorship.”

Hunter’s resolution wasn’t precisely what Murtha was advocating, but as the Republicans intended, it was close enough to confuse Americans and the media into believing we were voting on the Murtha proposal. Murtha was terribly upset by this. “I didn’t introduce this as a partisan resolution,” he said. “I go by Arlington Cemetery every day and the vice president, he criticizes Democrats? Let me tell you, those gravestones don’t say Democrat or Republican. They say American.”

For the Republicans this was smart politics; for Democrats it was a true dilemma. This resolution was a deadly serious version of the unanswerable question, Have you stopped beating your wife? If we Democrats voted for the Hunter resolution, the conservatives would smear us as cowards who wanted to “cut and run,” but a vote against the resolution would appear to be sanctioning the president’s “stay the course” position.

The Republicans were all going to vote against it. Even Duncan Hunter was going to oppose his own resolution. Democrats who supported it, blustered Republican Speaker of the House Denny Hastert, wanted to “wave the white flag of surrender to the terrorists of the world.”

“You all on the left opened up this debate,” postured Tennessee Republican Marsha Blackburn. “Now they would like to sneak out of the room and avoid this topic… They’re going to take the heat…” The Republicans had set it up to become a big political victory.

Before the vote, the Democratic caucus -- all the Democratic members -- met to discuss our strategy. We were split. For several hours we debated the pros and cons of the vote. Caucus meetings sometimes get very… democratic. There is no single, unified Democratic position, and we hear it in these caucus meetings. At this meeting, Democratic leader Nancy Pelosi spoke, our whip, Steny Hoyer, spoke, and Jim Clyburn, the chairman of the caucus, chimed in. We had experts on Iraq and foreign policy come before us to answer questions. There were divided opinions about what would actually happen if we withdrew our troops. People asked pointed questions. This was a tumultuous meeting; there was a great deal of shouting and ranting. There were angry people on both sides of this debate. Some Democrats against the war wanted to vote for the resolution, while others insisted it was a political trap and the party must not fall into it: Rather than debating the issue, this was simply another example of the Republicans using the war for political gain. The caucus ended with no final decision.

Inside my office, my staff and I continued to debate how I should vote. Eric and I were coming to realize that this was a rare opportunity for Democrats to put up or shut up on the war. He said, “I think Democrats should call their bluff... Let’s make them sorry for the day they did it. Let America talk about how the Democrats stood for something.”

I rarely have difficulty deciding how to vote on an issue. But this was a unique situation. “It’s not Murtha’s Resolution,” I said. “They think it’s a bad vote for Democrats to withdraw immediately. But this vote is still a referendum on how the president went to war and how he conducted it. I have no confidence in the president.” As I spoke my voice grew louder and louder. No one on my staff even seemed to notice. Most of us have worked together for a long time. “He’s running us into the ground,” I continued. “People are dying and I’m not voting with it anymore. It’s time to be mad as hell, and this is my mad as hell vote. If I vote no, I’m saying carte blanche, Mr. President, you’ve done the right thing. I’m not saying that. I wouldn’t have the vote this way, but we don’t get to pick and choose our votes.”

Finally we got a call from Fred Turner, chief of staff for Congressman Alcee Hastings (D-FL), informing us that a memo from our leadership had gone out. Nancy Pelosi had laid down the law: “The Democratic leadership recommends all Members vote no,” it read. Nancy believed it was extremely important that this internal debate within the party be kept within the party. That’s what a leader does. Publicly, we had to show a unified face. So the Democratic leadership had decided the best thing to do was vote as a bloc against the resolution, deriding it as a Republican grandstand ploy.

I turned on the TV to watch the debate taking place on the floor of the House. “Like the intelligence that led to war,” Californian Henry Waxman said, “the resolution before this body is a fake.”

Steny Hoyer labeled it, “the rankest of politics and the absence of any sense of shame.”

Massachusetts representative Jim McGovern protested that this resolution was a distortion of Murtha’s proposal. “Give us a real debate,” he said. “Don’t bring this piece of garbage to the floor.”

Even Jack Murtha was going to vote against it. But something just didn’t sit right with me, and I still wasn’t certain that voting no was the right thing for Democrats to do. I’d been terribly wrong when I voted to give Bush the power to commit troops in Iraq, and suddenly I was being given a second chance, which under Republican control was not likely to happen again.

Fred was still on the speaker phone with my staff. “There’s no good result for Democrats from this vote, agreed?” Fred asked Eric, stating the party position.

I jumped in and said, “Well, I actually think there is -- if two hundred Democrats voted yes and said this was a referendum on the president’s war in Iraq and we think it’s a lousy war that he’s running.”

Time had run out. My beeper announced that the vote had been called, and the television in my office showed the vote clock on the floor steadily clicking down. I still had to walk from my office across the street to the Capitol and get to the floor in time to cast my vote. In the minutes before I left, my staff and I huddled to discuss the issue for the last time. Lale Mamaux, my press secretary, said, “If you don’t want immediate withdrawal of troops you should vote no.”

“That’s not what this vote is,” I said. “This vote is about the president. This vote is about what Jack Murtha did yesterday.”

Eric and my legislative director, Jonathan Katz, were deeply concerned about the repercussions if I were the only yes vote. “I’m saying no,” Eric said. “N.O. But my heart says yes.”

When I walked out of the office I still wasn’t certain how I would vote. After I’d left, my staff took its own poll on how I’d finally cast my vote. It was evenly split.

On the floor of the House, Duncan Hunter had boasted that this would be “a clear and convincing no vote on the question of whether we should leave Iraq immediately.”

Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi countered that “Mr. Hunter’s Resolution... is a political stunt and it should be rejected by this House.”

“This is not what I envisioned,” Jack Murtha said. “Not what I introduced.”

Finally it was time to vote. For me, this vote was ultimately a referendum on the Bush administration’s Iraq policy. I decided that making a strong, clear statement in opposition to the president’s failed war strategy was the only vote I could live with.

The final vote was 403 against, three Democrats voting for the resolution. I was one of those three. Several Democrats criticized me for my vote, reminding me that other members who had been leaders in the anti-Iraq War movement had compromised their political position for the “good of the party” on this vote. I understood that, and I respected them. But this was my vote.

The Republicans had won an important political victory. The Democrats had suffered another humiliation -- manipulated into giving the President a nearly unanimous vote to stay the course in Iraq. But the fact was that we had all lost. It is cynical votes like this one that have contributed greatly to the almost universal disdain in which the American public holds Congress. The Republicans had their strategy, we Democrats countered with our strategy, and what the American people saw was nothing changing, nothing getting accomplished. It had become obvious to a majority of the public that the administration had no coherent plan, that our troops were bogged down, and that the Republican Congress was doing nothing about it.

Today Democrats have a small majority in the House and Senate, but unfortunately Congress is still held in extremely low regard. That’s not surprising; as an institution, Congress has rarely been a popular branch of government. Actually, that’s slightly misleading: Most people like their own representative but don’t think much of Congress as a whole. There are several reasons for this dismal state of affairs. I don’t think most people are fully aware of the breadth of the activities carried out by members of Congress. I know that as Democrats, our party is diverse and diffuse. And President Bush has blocked much of what we have tried to accomplish.

But mostly I believe people hold Congress in such low esteem because they don’t see substantial results. They’re mad as hell, too. In 2006 the country voted for a Democratic majority with the expectation that Washington would change, but we have not delivered. Things haven’t changed enough, and people have justifiably gotten upset.

If people saw congressional action positively affecting their everyday lives, they would have an entirely different perspective on Congress. But we haven’t fought those difficult battles, so instead people focus on a system that too often appears to be hopelessly deadlocked.

What I’ve tried to do in this book is take you inside the House of Representatives. I hope to give you a broad picture of what it is members of Congress do when we go to work every day. The job of a congressman actually does extend from the shelves of your grocery store to remote capitals throughout the world. Some of what we do will surprise you, and I suspect some of it will disappoint you. I hope to show you how the system actually works, how a bill really becomes a law, and a bit of the human side of being a member of Congress.

In addition, I want to give you a sense of a political life, from my first election to my present position. I am proud and privileged to be a member of the United States Congress. It’s a job I love. Often it’s a terribly frustrating job – but those frustrations are balanced by remarkable moments when my work has affected lives in a positive way.

And finally, I want to proclaim on every page of this book that I am a liberal Democrat and proud of it. I am tired of watching conservatives distort the meaning of liberalism in their quest to divide the country for their partisan purpose. I’ve watched as the conservative leadership collaborated with an out-of-control executive branch to diminish the powers constitutionally granted to Congress. By our inaction we have allowed the Bush-Cheney administration to expand its reach -- in secrecy -- far beyond what was intended by the Founding Fathers and create an imperial presidency.

I want to bring you inside the system in the hope that we can begin to change it together.

Copyright © 2008 by Robert Wexler. All rights reserved.