Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

| Acknowledgments | p. vii |

| Foreword | p. ix |

| Introduction | |

| Who Is Joey D.? | p. 5 |

| orà Why Are You Reading This Book? | |

| What Is Biomechanics? | p. 15 |

| orà Creating Movement, Not Chaos | |

| Biomechanics and the Golf Pro | p. 25 |

| orà Don't Just Take My Word for it | |

| How to Use This Book | p. 29 |

| orà Here Are The Rules | |

| Biomechanical Assessments | p. 33 |

| orà Why You Bought This Book | |

| Shoulder-Rotation Prescription | p. 47 |

| orà Better Accuracy and Increased Distance. That's Ail. | |

| Upper-Body-Rotation Prescription | p. 57 |

| orà Curing Your Arms-Y Swing | |

| Lower-Body-Rotation Prescription | p. 69 |

| orà Discovering Your Hips | |

| Pelvic-Tilt and Posture Prescription | p. 77 |

| orà Align Your Spine | |

| Balance Prescription | p. 83 |

| orà Finding New Power | |

| Full-Body Strength and Coordination Prescription | p. 91 |

| orà Mr. Upper-Body, Please Meet Mr. Lower-Body | |

| The Joey D. Dozen | p. 97 |

| orà the Twelve Secrets of the Pros | |

| Structuring Your Workouts | p. 123 |

| orà What Am I Supposed to Do? | |

| Your New Golf Body | p. 135 |

| orà Now What? | |

| Appendix | p. 147 |

| Table of Contents provided by Ingram. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

1 Who Is Joey D.?

or... Why Are You Reading This Book?

Joey D.,“ Vijay Singh said with a giant smile on his face. “You sounded taller over the phone.”

The first time I met Vijay Singh, he insulted me. I instantly liked him.

This was back in 2001. He’d heard some good things about me and thought maybe something about this unorthodox golf coach with some unorthodox training methods could help him take his game to the next level. Vijay and I worked together for a few months, and in March 2002 he notched his first tour victory in almost two years by winning the Shell Houston Open by a comfortable six strokes.

He invited me to fly back to Ponte Vedra, Florida, with him on his plane.

“What would it take to get you to work with me exclusively?” he asked me. Before I could even start to consider the offer, he added, “I know I can be the best player in the world.”

In 2002, everyone just assumed that Tiger Woods was invincible and would be number one in the world for as long as the sport of golf interested him. Vijay Singh was a PGA Tour Rookie of the Year in 1993, but had managed just a single tour win since 2000. Here he was, though, telling me that he thought he could be number one. Most people would have laughed at his prediction, but I knew how hard a worker he was. In the time I had been with him, he’d just about kill himself whenever we worked out. I respected his work ethic immensely, but I also knew that trying to overtake Tiger would be going up against some stiff odds. I knew something about facing insurmountable odds, though.

I sold my training facility in south Florida and moved north to Ponte Vedra.

In September 2004, Vijay outshot Tiger Woods and Adam Scott by three strokes to win the Deutsche Bank Championship in Norton, Massachusetts. As a result, he leapfrogged over Tiger and into the number one spot in the world. Thanks to hard work and a team of dedicated and knowledgeable professionals, Vijay had made good on his prediction. In April 2005, when he was elected into the World Golf Hall of Fame, Vijay thanked several people in his acceptance speech. I was one of them. I sometimes wonder what it was that made me uproot my life to go work with him, and I always come back to what he said to me on that flight from Texas: “I know I can be the best player in the world.”

Something about his confidence and determination reminded me of someone.

NEW JERSEY

As a kid, I would never accept anything but 100 percent of myself. I played football in junior leagues and developmental leagues, and I recognized early on that I was stronger and faster than the other kids. Physically, I was pretty lucky in my genetics. But mentally, I just approached the game differently from my friends. The way I thought about things was completely different from anybody else’s. I’d see things that no one else saw. I recognized I was a leader because I had no fear of anything at all. That could have been a good thing or a bad thing, but it made me relentless in just about anything I did.

I never wanted anyone to drive me to football practice, for example. I wanted to ride my bike to practice because, I used to think, if I rode my bike, I would already be ahead of the curve when I got there. And if we didn’t win a game, I would come completely unglued. Everybody would leave to do whatever they did after a game, and I would just stay there doing drills and running for hours. I grew up in Manalapan, New Jersey—a typical suburb in Monmouth County. In the late summer, I knew that football season was right around the corner, and I would run up and down the hills. It’d be light out when I started, and eventually the sun would go down and it would be dark and I’d still be running. It’d be nine at night and I’d still be out there. I used to tell myself, “I need to be faster. I need to be in better shape than anybody else when I get to the first day of practice.”

When the season started, I was always in the best shape I could possibly be in. Couple this with my natural skills, and I was a monster on the field. They’d put me on the bench after the first half because I was destroying people. Opposing coaches constantly questioned my age, saying I had to have been much older than I said I was.

I’m not sure where this extreme work ethic came from. I come from an average middle-class family. Everybody worked and everyone had this dream and vision to better himself. You were taught from the beginning that hard work was the key to success—on the field, in the classroom, everywhere. My dad was demanding about grades. If I wasn’t on the honor roll, I couldn’t play any sports. It drove me to understand the importance of education. And since I was so driven about getting in the best shape I could be in, it was natural for me to start learning as much as I could about how the body worked.

From a young age, I started studying what I could do to make myself a better athlete. I knew it was more than just pure strength—more than just how much I could bench-press or how much I could squat. Being an athlete was about knowing how to use that strength in motion. The strongest guy on the field is just the strongest guy on the field unless he knows how to use that strength in the particular sport that he’s playing. By then, I had branched out from just playing football. I had started wrestling and began studying martial arts. I was continually amazed at how these lighter-weight-class wrestlers and my martial arts instructors—at maybe 130 pounds—could do these incredible things with their bodies. They generated the same amount of strength and power and explosiveness as much bigger guys. I started to become obsessed with figuring out where this ability came from. How could these small individuals have this power and transfer it through movement and have such amazing results? In my head, I began to think about how these movements and movement patterns could be applied to other sports with similar results. That’s when I started to really understand movement strength.

Unfortunately, both my research and my football career were about to be put on hold.

SETBACKS

Two months before my eighteenth birthday, I was diagnosed with testicular cancer. A biopsy later revealed that the cancer had spread and had developed into lymphatic cancer. Despite all the work I had put into my training and into my body, I had a terminal disease. I saw a ton of doctors and surgeons, and at the end of most of these visits, someone in a white coat with a serious expression on his or her face would ask me what I’d like to do with the next—and final—ten months of my life. All of a sudden, at eighteen years old, everything I had ever dreamed about was gone. It was surreal. All of these specialists were telling me that I was going to die, but I still felt great. I felt as if I could run through walls.

I approached my sickness the way I’d approached just about everything else up to that point in my life. Because of who I was, I wasn’t simply going to lie down. I couldn’t. It just wasn’t part of my makeup. Eventually, I found a doctor who was willing to take a chance on surgery. He told me about an invasive and difficult procedure. He said he was willing to try it because he was convinced I was strong enough to handle it. I thought back to the long and painful hours I’d spent in the gym and running those hills. All that time I thought I had been training for football.

Then the real game began. I went into the hospital and they did all of these extensive tests and scheduled me for major surgery. They told me that the procedure would take a certain number of hours, but when they went in, they found a lot more problems than they expected. I was fighting for my life. I made it through the surgery, but no one was sure if they got all of the cancer or if it had spread somewhere else.

Chemotherapy treatments started and the months started to go by. At the time, chemo wasn’t outpatient for most people. I had to be in the hospital seven or ten days at a time. Over a year and a half, I went from a ferocious 218-pound teenager that was going to take the football world apart to an emaciated 140-pound kid. On top of the weight loss, the chemo affected all of my senses. I lost all of my senses. I had no sense of taste. I had no sense of feeling. I had no strength. I was sick constantly. It was a nightmare. But I survived.

Call it destiny, the work of God, what ever. I don’t want to get caught up in all of that. My personal belief is that it wasn’t really my time to go. With a clean bill of health, I now had to rebuild what was left of my body. I spent the next eighteen months strengthening and reteaching my muscles how to do the things that they used to do so effortlessly and naturally. My body bounced back. (If you’re a collector of old muscle magazines, which would immediately make me very suspect of you, check out the August 1991 issue of Robert Kennedy’s Muscle Mag International. It has a feature on me and my illness, recovery, and subsequent success as a trainer.) At age twenty-two, I had fought back and conquered a terminal illness. My dream of playing college or pro football, though, was gone.

SOUTH FLORIDA

In the mideighties, I moved down to West Palm Beach. I figured that if I had built—and then rebuilt—my body using principles I’d developed, it was time to see how these theories worked on other people. I’d helped out people in the gym all of my life, but Florida would give me access to a different breed of client—the pro athlete. A lot of NBA and NFL guys spend their off-seasons down there, and with around half of the Major League Baseball teams doing their spring training in the surrounding areas, it just seemed like the place to be. The challenge was getting the first few athletes to understand and believe in what I was doing. Once they saw how these methodologies really worked, word spread quickly. I started developing a reputation in the West Palm Beach area as a strength and conditioning coach that got results.

One of the first pro athletes I worked with was Shelton Jones—a former standout basketball player at St. John’s University. He was drafted in the second round of the 1988 NBA draft by the San Antonio Spurs and ended up playing the majority of his rookie season with the Philadelphia 76ers. It was a thrill to finally branch out into different sports—to be able to take these things about movement and strength that I’d learned as a kid by wrestling and studying martial arts and use them with this big six-foot-eight-inch basketball player to teach him how to become quicker and more agile on the court.

My work with Shelton led to work with other NBA players, such as Roy Hinson, whose career spanned almost a decade. Then came baseball players such as Tracy Jones, a former first-round pick who had a killer rookie season with the Cincinnati Reds, and Jeff Innis, a pitcher who spent his entire career with the New York Mets. Of course, Florida is also a hotbed for high school and college football. There was no shortage of work getting high school kids ready for the collegiate game and college kids ready for the NFL combines, where they would have one last chance to impress the pro scouts with their talents. It was an incredibly rewarding and fascinating ten years.

BORN TO RUN... AND STRETCH... AND STRENGTHEN

In the late nineties, my reputation started to expand beyond just the sports world. In 1999, I got a call from Clarence Clemons—the sax player from Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band. He had just had his hip replaced and was looking for someone to work with him on rehab and strengthening during the band’s upcoming world tour. So I left my facility to go out on the road helping Clarence. Through him, I met—and start working with—Nils Lofgren. That led to work with Stevie Van Zandt and then, finally, Bruce and his wife, Patti.

After spending so long just concentrating on how specific strengths and movements were used in competitive sports, it was an amazing chance to see if the things that I taught could be applied in a nonsports situation. And I couldn’t have asked for a better—or more challenging—group to work with. These guys had been on the road for just about their whole lives, and the rigors of that lifestyle were taking a toll on their bodies. As they got into their late forties and fifties, it was really forward-thinking of them to realize that they had to make sure that their bodies were in the condition necessary to allow them to continue to do what they loved to do.

It was an incredible assortment of challenges. Clarence Clemons was a huge, six-foot-seven-inch, three-hundred-pound man who had just had his hip replaced. Nils Lofgren, who was maybe five feet two and was a former gymnast and trampoline expert, was also suffering from hip problems. Stevie Van Zandt, the lead guitarist, was as stiff as a corpse and had a world of flexibility issues. And then there was Bruce Springsteen, who’s an absolute fanatic about his training and nutrition. Bruce was amazing. At fifty—and now sixty—the guy goes out night after night and performs for three hours while moving constantly. Think about that: he can sing and run at the same time... for three hours. Do you have any idea of the kind of conditioning that takes? The next time you’re on the treadmill, break into a sprint and try to belt out all five-plus minutes of “Thunder Road.”

When the tour ended, I headed back to Florida. Not long after, I got a call from an old friend, Eric Hilcoff, asking me if I’d ever consider working with professional golfers. Jesper Parnevik, a successful, charismatic, and quirky player, was looking for someone to help him out with his strength and conditioning. I’d worked with everyone from pro basketball players to pro baseball players to Rock and Roll Hall of Famers. Golfers? Sure, why not?

GOLFERS ARE ATHLETES... AT LEAST SOME OF THEM ARE

It’s funny. I come from a football background. I come from a wrestling background. I come from a martial arts background. Obviously, I don’t have a problem with intense sports. People see golfers walking around in slacks, polo shirts, and fancy shoes. Books and magazines talk about golf being a “gentle-man’s game.” You always hear about “golf etiquette.” I am an in-your-face guy. Just ask any of my players. People that know me are constantly asking me what the heck I’m doing in this sport. They think I should be out on some frozen field in Green Bay or Buffalo working with NFL linebackers, or in some dingy, sweat-filled room right out of Fight Club helping some mixed-martial-arts fighter getting ready for his next bout in the Octagon. The last place they picture me is out on some lush fairway somewhere in Hawaii or Arizona hanging out with a bunch of tanned guys dressed in “business casual.”

If you had asked me as a kid if I could see myself as a coach in the NFL when I was in my late thirties or early forties, I would have been thrilled with the thought. With my playing days over, it would have been exciting to help younger players make the best of their bodies and abilities in the game. Looking back, though, I think that having had to battle cancer and losing the chance to see if I could make it in the NFL may have made me shy away from football. Maybe because I never got to accomplish a goal I had set for myself, I decided to look elsewhere. I don’t want to make it sound as if I’m looking for pity. Anyone that knows me knows that’s the last thing I look for. I don’t accept a “pity poor me” attitude from my players, so I sure wouldn’t accept it from myself. It is what it is, and I think the experience forced me to look for another outlet for my decidedly football mentality.

So how did I end up in golf? Why didn’t I just stay on the road with Springsteen? How could a kid from Jersey possibly turn down a chance to live the rock-and-roll life with the Boss?

I got an insider’s view of the golf world when I started working with Jesper. I saw a blank canvas. All of the things I knew about the body and biomechanics—and had used to improve athletes in other pro sports—were completely foreign concepts. These things weren’t part of the golfer’s normal routine. I had the chance to start to dissect the sport, break down the essential movement patterns, and develop things that I knew would work by identifying the way the body needs to work in golf—not as it works in football, not as it works in basketball, but as it works in golf. Once I understood how truly complex the golf movement is, it was easy to begin to teach players how the body has to work—and why it sometimes doesn’t work—biomechanically. Just as I did in south Florida, I started to develop a reputation.

Another thing that drew me in was being able to see a side of the sport that most golf fans may not even know exists. A lot of these players have an intensity and a competitive fire that viewers don’t see when they watch a tournament on TV. Some guys may say they’re just out there playing against the course, but others say that they’re going to hit it fifty yards by the other guy all day long. You develop friendships and relationships with other players during the pretty long season, but I don’t care if you like someone or not, you don’t want him outhitting you by fifty yards on every drive. You don’t want him making a birdie every time you shoot par or shoot par every time you make a bogey. What gets lost a lot of the time on TV is that these are competitive individuals. You don’t see players trying to distract another player when he’s about to tee off. They’ll talk, they’ll move, they’ll stand too close to the guy when he’s going through his pre-shot routine. They know all about the so-called etiquette of golf, but they’ll do these things just to try to get into the guy’s head and mess with him. You don’t see this on TV—and you definitely don’t get to see (or hear) the expletive-filled threat whipped back at the guy trying to do the distracting. Golf may be a gentleman’s game, but these gentlemen know how to drop some serious f-bombs.

A lot of the golfers that were working out with me were guys that were indecisive when growing up about which direction to take their athletic skills. They may have played baseball or basketball in high school—and some of them, such as a Pat Perez or Jason Dufner, had the talent to play, say, pro baseball. But they had to decide about their future. Most of the time they chose golf because of some injury that wouldn’t let them play another sport at an elite level.

These guys have always considered themselves athletes. And athletes attract athletes. Think about it. What do most football players, basketball players, and baseball players do in their off-season? They golf. Because of the many celebrity pro-ams, a lot of pros from other sports have befriended pro golfers. This crossover—now more than ever—has reaffirmed to the guys on the tour that they are truly athletes.

That said, not every guy on the tour was going to want—or be able—to work with me. To paraphrase Chris DiMarco, a lot of them just didn’t want any part of me. They may be competitive when they’re out on the course, but they’re the guys I would have beaten up in high school for their lunch money. You have a lot of players that come from money and have spent their whole lives in country clubs. And that’s where I saw the challenge. Guys would look at me and tell me they wanted no part of me. I was too aggressive, too intense. I was told by other coaches that when you work with some of these guys on their biomechanics, you have to have a soft touch. You can’t be too aggressive. My response? Don’t tell me how to do my job. I’m not going to change who I am simply because they weren’t used to my approach. Golf is evolving, though, and now they’re more accepting of how rigid and demanding I can be because—well—they see the results. I’m not very accepting of someone’s saying he can’t work out because he’s too tired. I’ll get on the phone and tell him that he needs to come work with me. Do they like it? Probably not. But I get them in here—whether they’re in the mood to work or not—and we do things that make them better as professional golfers.

Of course, then you have someone like Vijay Singh, who grew up in Fiji. He played barefoot as a kid. When I went there with him, it was amazing to see what the sport had done for him. He’s beyond famous there. It’s surreal. He’s on a postage stamp. Everyone—no matter where he goes—knows him and loves him. Here is a guy that, in his late thirties, decided that he was going to change his body to make it able to do everything he needed it to do. Whether it was four in the morning or ten at night, he never gave less than 100 percent when we trained. It was an honor to travel around the world with him and also to see where it all started for him. I’m guessing it is a far cry from where most of today’s touring pros got their start.

“Joey D.,“ he said one time when we were in Fiji, “let’s go see the course I grew up playing.”

So we get in the car and not only do we drive to the course, we drive right onto the course. I was like “Vij, what are you doing?” and he calmly says it’s okay to drive on the course. It was mind-blowing. Imagine driving a car onto the most pristine fairway or green at Pebble Beach or Augusta National. Of course, the holes he grew up playing weren’t quite as manicured as those on the PGA Tour. You could barely tell where the fairway started or ended or where the green was. Parking, though, wasn’t much of a problem.

TODAY

I don’t care what you do for a living, if someone can make you better at whatever you do—can improve you to the point where you’re more successful and earning more money—you do it. It’s a no-brainer. I’m giving you information that if you use it and apply it, it’s only going to help you to stay injury-free, to discover your weaknesses and overcome them, and to take your strengths and make them more effective. You put all of these things together, and when you step up to the first tee, you have such confidence because you know you’ve worked on things again and again and again with this insane guy who doesn’t really look like your normal golf-biomechanics coach.

My job is to bridge the gap between the Old World Golfer and the New World Golfer. But it’s getting easier; even on the Champions Tour (formerly the Seniors Tour), you have Kent Bigglestaff working with guys in their fifties and older. Twenty years ago, you had guys that wouldn’t even have considered going to a gym. After a round, they’d head straight to the bar. There’s still a touch of that. Some guys will come into our trailer and look around as if they’d just landed on a foreign planet. “Is this where I get a rubdown?” they’ll ask. I’ll look at them and say, “No. This is the trailer for athletes. It’s where work gets done. It’s where biomechanics are assessed and worked on, and where core strength, coordination, and cardiovascular endurance are improved.” Okay, maybe I don’t say it that nicely.

What’s so exciting about golf-specific training and conditioning is the level of acceptance it’s achieved. By the time that Vijay and I decided to go our separate ways in 2007, the biomechanical approach that we had taken was no longer looked upon as crazy or outlandish. I’m no longer the nut running on the beach playing a game of “medicine-ball catch” with a touring pro. Now I’m the nut teaching about biomechanics and the science of movement at the PGA Tour Academy at TPC Sawgrass—the St. Andrew’s of America. I’m working with more than a dozen touring pros who, week after week, are still vying for the top money late into Sunday afternoon. I’m working with some of the top junior golfers in the country to help them understand the science behind what it’s going to take to be successful at the high school, collegiate, and—eventually—pro level. And I have a wonderful working arrangement with Greg Hopkins and the people at Cleveland Golf.

Maybe even more thrilling, though, is that these tools and teachings can be used by anyone. Age isn’t a limitation. Experience isn’t a limitation. Equipment isn’t a limitation. I don’t care if you’re a touring pro or a recreational player with a thirty handicap. Golf is just a series of biomechanical movements, and we are all bound by the laws of physics. To achieve the results you want, you have to be able to do certain things with your body. Only by making the necessary changes in your body will you have the ability to master the complexities of the golf swing and be able to play the game better and enjoy it more. My program was developed—and used successfully—by the top players in the world, but it isn’t just for pros. This is for everyone. This is for the world of golf.

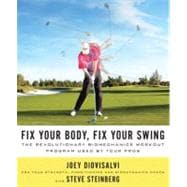

Excerpted from Fix Your Swing by Joey Diovisalvi and Steve Steinberg.

Copyright © 2010 by Joey Diovisalvi and Steve Steinberg.

Published in January 2010 by St. Martin’s Press.

All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproduction is strictly prohibited. Permission to reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the Publisher.