|

1 | (64) | |||

|

65 | (76) | |||

|

141 | (38) | |||

|

179 | (42) | |||

|

221 | (22) | |||

|

243 | (54) | |||

|

297 | (52) | |||

|

349 | (30) | |||

|

379 | (20) | |||

|

399 | (16) | |||

|

415 |

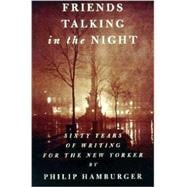

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

TALK

* * *

In many ways, Talk of the Town was the heart and soul of The New Yorker . Notes & Comment took up the first page and represented the editorial stand of the magazine. Then followed the Talk stories themselves (people, places, up, down, all around), each one a complete entity written with great care and deep respect for the English language. I have never quite recovered from the experience of joining the staff and having my Talk pieces edited by Harold Ross himself, on Friday evenings in his office, line by line. I think it was Mr. Ross's way of sizing up his new young nonfiction staff people. He made it clear that, above all, he was looking for content laced with humor. And there was a certain grandeur to the anonymity of Talk, the sense of being part of a prideful institution Mr. Ross also established the policy that any Talk story, although unsigned in the magazine, could be reprinted in a book with full credit to the writer.

APRIL, 1939

Bettmann Archive

* * *

One of the many local enterprises for which we must thank Herr Hitler is the Bettmann Archive. The Archive is a collection of some fifteen thousand photographs of old manuscripts, works of art, mechanical devices, historical characters, household objects, and whatnot, intended to tell graphically the story of man and his work through the ages. It was started ten years ago by Dr. Otto Ludwig Bettmann, then head of the Rare Book Department of the Berlin State Art Library. He went about the libraries and museums of Europe with a Leica, gathering material on the history of reading. This proved so interesting that he branched out, building up a file of several thousand pictures on many subjects before 1935, when he lost his position and had to leave the country. Casting about for a livelihood in the United States, he decided to exploit his Archive commercially. Now he has a chromium-furnished office on West Forty-fourth Street, and four office assistants--another refugee and three Americans. He is consulted principally by school authorities, publishers, magazine editors, and advertising agencies. The pictures are enlarged to five-by-seven-inch glossy prints, and sell for from five to ten dollars, depending on their rarity and the size of the order.

Dr. Bettmann can dip into his Archive and come up with a pretty complete photographic history of almost anything that might pop into your head--Beautiful Women, Corsets, Headaches, Love, Pain, Plumbing, Rain, Shaving, Sugar, Traffic, Umbrellas, or Vegetables. His file on Trailers goes back to 300 A.D. When Dr. Bettmann and his colleagues run across an old and interesting picture, they try to figure out some angle that would give it commercial value, and are usually successful. Recently, for example, they came across an old print of some medieval schemer who had worked out a system of communication whereby people with megaphones relayed messages from hilltop to hilltop; this they sold to a broadcasting company as a picture of the first network. Lately Dr. Bettmann has been busy working up a history of Fur, which was put away in Jaeckel's cornerstone; it will hardly matter, in the cornerstone, whether the record is comprehensive or accurate, but Dr. Bettmann's Teutonic conscience kept goading him to perfection. The fastest-moving item at the moment is Umbrellas; he thinks Chamberlain is responsible for that.

Dr. Bettmann, a spare fellow of forty or so, is happy as a lark in the United States. He has married an American girl, and they live out in Jackson Heights. He keeps up his academic contacts by lecturing occasionally at Columbia or the Brooklyn Institute. He's endlessly pleased by the ease with which you can consult a book in an American library, or get an interview with an American executive. "In Germany, it's all letters and formality," he told us. Another pleasant novelty is the way our scholars keep up with political and social problems. Dr. Bettmann knows moments of despondency, his colleagues told us, usually when business has slacked off. Then he sits in his office, muttering, "What can we do? What can we do?" Then, likely as not, somebody will call up for a pictorial history of Happiness, and he's a new man.

APRIL, 1940

Mr. Shakespeare

* * *

We hadn't been to a seance for some time, so we accepted an invitation to one at Dr. Edward Lester Thorne's United Spiritualist Church the other evening, the more readily because it was announced that William Shakespeare was to attend. Dr. Thorne, who turned out to be a stout, earnest medium, had promised to produce Shakespeare in spirit and knee breeches, hoping thus to collect the money which the Universal Council for Psychic Research offers to the first medium who can produce anything in the ghost line that can't be duplicated by natural means. Joseph Dunninger, the illusionist, is head of this organization and he was present, along with the press and a number of friends of Dr. Thorne, of both sexes. The church is a room on the second floor of a building at 257 Columbus Avenue, over a drugstore, and there all assembled before a black-curtained cabinet. Dr. Thorne began by telling the gathering that Shakespeare had already visited him on four occasions, that he had popped in first without warning and said casually, "I am William Shakespeare." The room was filled with a heavy, sweet perfume. "That's Bacon," said a man from the Sun . Along with others, we inspected the inside of the cabinet and found no sign of Shakespeare's spirit, or anything else. Poking around behind it, we came upon a pulpit, which, we gathered, was for use on more solemn occasions, and in it we saw such natural phenomena as a can of Alka-Seltzer, a bugle under a glass bell, and a sign reading, "Doctor Out. Will Return at Six." Everyone sat down facing the cabinet and Dr. Thorne went into it, closed the curtains, took off all his clothes, and threw them out. Dunninger thereupon went in, carrying a black robe, to inspect him. He came out a moment later. "The gentleman is quite nude," he said with dignity.

While Dr. Thorne was going into a trance, a group of his friends in the back of the room struck up some hymns. These included "Abide with Me," "There's a Land Fairer Than Day," and "Where He Leads, I Will Follow." The room was dark except for several dim blue lights, the largest of which flickered over a portrait of Dr. Thorne with a halo. Presently eager little moans were heard from the cabinet, followed by a high, girlish voice. "Hello," it said. "Hello," called back one of Dr. Thorne's friends. "That's his spirit control, Sunbeam," explained a lady next to us. "My momma's here, my poppa's here," squeaked Sunbeam, "and Mr. Shakespeare is right beside me." At this point your correspondent was hit in the face by a rose which sailed out of the cabinet. We put it in our buttonhole. "I will count to three," continued Sunbeam, "and the cameramen will take pictures of ectoplasm." Sunbeam counted to three, and what appeared to be a face towel waved across the opening. The cameramen didn't get organized quickly enough and missed the picture. The ectoplasm obligingly returned and waved again. There was a slight pause, more moaning, and finally a deep bass voice. "Thou hast asked for me and here I am," it said. "I am Mr. William Shakespeare." Shakespeare went on to say that he and Bacon were one and the same person. "I want you to get that clear," he told us, and he seemed to mean it. Suddenly a thin, white face, with a white goatee, appeared at the opening, staying long enough to have its picture taken. Mr. Dunninger seemed unimpressed. "Come out, Shakespeare," said Dunninger. "Come in, Dunninger," said Shakespeare. Along with Dunninger and a Mr. O'Neill of the Herald Tribune , we went into the cabinet. No Bard. No Sunbeam. Only Dr. Thorne in a black robe and a cold sweat. "Give me air!" cried Dr. Thorne, coming out of a trance that seemed genuine to us. He staggered from the cabinet and drank a Coca-Cola.

Dunninger said that he had seen a face but that he wasn't a bit mystified. "I can produce an elephant from that cabinet," he announced, "or three girls and Julius Caesar." No one disputed him. Dr. Thorne looked disappointed when Dunninger told him that he wouldn't get the money. One of the women in the back said that Shakespeare had red eyes and looked tired. "Excuse me," said Dr. Thorne suddenly, rushing across the room, "but you are stepping on my drawers."

SEPTEMBER, 1940

Refugee Reading

* * *

Literate, intelligent refugees from the Nazi-dominated countries gravitate frequently to the Public Library when they come to live here, and most of them talk over their problems with Miss Jennie M. Flexner, an alert and kindly lady who has served as Readers' Adviser there ever since the position was inaugurated, eleven years ago. Miss Flexner and her staff are at the service of any reader who wants a bibliography of special reading drawn up for him. In the case of the refugees, of course, the demand is always for books that will help the new citizen to understand the United States--its language, customs, history, and geography. Foreigners are more geography-conscious than native Americans, for some reason. In outlining courses of reading for refugees, Miss Flexner tries to slip in literary antidotes for what she has discovered are the three great misconceptions about this nation: (1) that gangsters lurk on every hand, making it dangerous to venture out after dark, (2) that political graft is rampant in every department of the government, and (3) that one must never discuss politics where there is any danger of being overheard.

The refugee newspaper is the Times , with no close second. They read it patiently, from beginning to end, using a dictionary if necessary. "The Epic of America" and "Only Yesterday" are about tied for the non-fiction honors. Other popular non-fiction titles are "Middletown in Transition," "John Brown's Body," and "The Autobiography of Lincoln Steffens." Willa Cather is the most popular novelist. There is a steady demand, among refugees, for "Alice Adams," "Ruggles of Red Gap," "Laughing Boy," "So Big," "Hugh Wynne," and "The Scarlet Letter." People just beginning to explore our literature are tactfully steered away from fantasy, social caricature, and proletarian indignation, on the theory that it would needlessly confuse or depress them. There was hell to pay one time when a refugee got hold of Robert Nathan's "One More Spring," which you may remember as a super-delicate fantasy about the Central Park Hooverville. He brought it back and asked for a detective story in German instead. "What's going on in your parks?" he asked Miss Flexner.

Europeans are fascinated by the American Indian, and take out all sorts of books on the subject, both fact and fiction. (James Fenimore Cooper is, or was until der Fuhrer purified the libraries, a great favorite in Germany.) Some of the refugees can't get used to the idea of an impartial, unpropagandized library. One German lady, discovering on the shelves a copy of Streicher's Der Sturmer , ran out of the room with tears streaming down her cheeks; one of the attendants caught up with her, and convinced her that the Public Library hadn't gone Nazi. It turns out that the American novelists who have been most popular abroad are Lewis, Dos Passos, Dreiser, Hemingway, Upton Sinclair, and Joseph Hergesheimer. Miss Flexner is not convinced that this is all for the best. Whenever it is suggested to a refugee that he might find greater opportunities outside of New York, he is likely to turn pale and murmur, "Must I go to Main Street? Must I live in Gopher Prairie?" The Library people try to explain that "Main Street" is the result of a tantrum which Sinclair Lewis got over years ago, but it's uphill work.

DECEMBER, 1940

Tunneller

* * *

What we want to be when we grow up is a tunneller in Macy's. To explain what a tunneller does, we first have to describe Macy's conveyor system, by which packages are sent from the wrapping rooms on each floor to the loading platform in the basement, where they are put into the delivery tracks. The conveyors are spiral metal chutes, about three feet high and two and a half wide. They go round and round and down; or, in other words, they're like spiral staircases, only they're chutes. That clear? There are twenty-four of them, in groups of three, throughout the store. Many times a day, but especially around Christmas, the basement-bound parcels get jammed in the chutes. Macy's employs six men as tunnellers, to dive into the chutes, slide down to the place where the jam has occurred, and start the packages moving. The senior tunneller, a stocky Irishman named Mike Reynolds, has been at it for twenty years.

Expounding the technique of his peculiar job, Reynolds told us first that the only equipment he carries is a flashlight. He wears overalls and waxes the seat of them. The architects who installed the chutes expected that trouble-shooters would be lowered into them by ropes, but this didn't work out; the winding of the chutes created too much friction. It was Reynolds who developed the proper technique. He climbs in, feet first, braces one shoulder against one side of the tunnel and his feet against the other, and, zip , he's out of sight. By pressing harder with his feet, he can slow down, or come to a complete halt. Reynolds used to work in his bare feet, but switched to rubber-soled shoes several years ago, after sliding into a rather messy can of spilled Maltose.

The surface of the chutes is waxed, and most of the pileups result from packages coming to a dead stop on surfaces where the wax has worn thin. During the Christmas rush, the trouble is usually caused by parcels carelessly tossed in by temporary helpers. These weeks, Reynolds makes about two hundred descents a day. He has the job of breaking in new tunnellers, who are invariably terrified. Reynolds gets in first, and the two of them slide down together, Reynolds showing the fledgling how to handle himself, and remarking occasionally, "See? Nothing to be afraid of." Most of the chutes have an opening on every floor, but several drop five flights without a break, and one levels out at a point over the executive offices. There is no interruption of normal activity when Reynolds goes into a chute; the packages continue to slide down along with him. He allows small packages to pass him, and supports big ones with his shoulder until he can clear the way. Then he climbs out at the next exit. Once he was severely conked by a chair rushing down behind him, but he can remember no other disasters. The other day, one of Reynolds' colleagues was tussling with a large, unruly package, trying to get it unstuck, when another piece of merchandise, equally immense, swept down and pinned him against the first package. No word having been heard from this man for an alarming interval, Reynolds went to the rescue, travelling along on a tide of Christmas gifts. "I was up to me ears," he told us. The man was rescued O.K., you'll be glad to learn.

Reynolds' big moment comes at the end of the banquet which some of the employees hold once a year, just after Christmas, in the restaurant on the eighth floor. When it's time to go home, Reynolds bids his friends good night and dives into a chute. It's always an effective exit.

MAY, 1941

Emergency Messengers

* * *

We were one of the handful of journalists who attended the Army's pigeon demonstration at Rockefeller Center last week. We got to Rockefeller Plaza just in time to dart off by subway to Kew Gardens with a private and two pigeons. Six other privates, each bearing one or two pigeons in wicker baskets, headed at about the same moment for other outlying parts of the city, where they planned to release the birds. The role of the pigeons was to rush back to Rockefeller Plaza, thus demonstrating that in the wartime event of every other means of communication being destroyed in New York City, the birds could carry on. The pigeons we accompanied were Nos. 1054 and 1064, and their custodian was Private Felix Orbanoza, of the Signal Corps. Pursuant to orders, we all took an F express (Parsons Boulevard) at 11:10 A.M. While we were roaring to Queens, Orbanoza shouted to us that all the pigeons involved hailed from Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, and that, to the number of fourteen, they had been living in a trailer in Rockefeller Plaza for a week, establishing home ties. They had previously taken short excursions through the canyons of midtown, and once had visited Harlem. Except for two of them who were eaten by a pair of hawks that hang out behind Saks on Madison Avenue, they had all made successful preliminary journeys.

Throughout the subway ride, Nos. 1054 and 1064 maintained a calm, indifferent air. Private Orbanoza told us that a pigeon man must become intimately acquainted with his charges and practically live with them. He himself does his reading in his pigeons' loft, allowing them to look over his shoulder. We arrived at Kew Gardens at 11:34 and Private Orbanoza ducked into a drugstore to phone his sergeant back at Radio City. He ducked out again, hurried across the street to a vacant lot, and turned the pigeons loose. They swooped into the air, heading first north, then west, then east, and flew away.

We tore back to Radio City to see if a man could beat a pigeon by subway, arriving there at 12:06 and learning that No. 1064 had got in three minutes earlier and finished his lunch. That made his time twenty-four minutes. There was considerable talk of Mac, an old service bird, who had already returned from Washington Heights, and a blue-checked hen who had made it from Hudson Terminal in fourteen minutes. A brigadier general, a major, and several other commissioned officers sat around a table in the Plaza waiting for the birds to check in. They did so with such regularity that it was decided to add interest to the proceedings by taking Mac to the top of the R.C.A. Building for a nose dive. Mac was liberated, and to cries of "There's Mac!" dived like a Stuka, levelled off over the British Empire Building, and landed beside the brigadier general. Mac thereupon cooed for his lunch, reminding a man from the Rockefeller Center staff that the commissioned officers and reporters had been invited to lunch in the Rainbow Room. No. 1054 hadn't come in when we left, but soon after we sat down it was announced that all the pigeons had returned. Squab was served for lunch, which we assumed was just a coincidence.

JUNE, 1941

Basenjis

* * *

We paid no attention whatever to the 3,870 barking dogs at the Morris and Essex Kennel Club Show in Madison, New Jersey, the other Saturday, our sole and limited objective being the four Basenjis, the barkless dogs from the Belgian Congo. We pushed determinedly through howling ranks of schipperkes, schnauzers, papillons, Pekes, and pugs, and finally found the Basenjis in a far corner of one of the tents, quietly watching a fat poodle being sprayed with an atomizer. The Basenjis had satiny brown coats and the build of fox terriers; their faces bore the wrinkled, worried expression of investment counsellors. They were in charge of John Lang, a sallow, barkless keeper who had brought them to New Jersey from the Aurora, Ontario, kennels of their owner, Dr. A. R. B. Richmond, who imported them from England a year ago. They are one generation removed from the Congo. Lang pointed out to us Koodoo and Kwillo (males) and Kiteve and Kikuku (bitches). "In the kennel, Kiteve is called Stella and Kikuku is known as Fatty," Lang told us, and at the sound of their names the bitches uttered a strange, singing chortle. "They're oodling," said Lang. We asked him about the nature of the oodle. "You know--oodle," he explained. "Like Swiss oodlers."

Lang told us that Basenjis are highly prized as hunters in the Belgian Congo and the natives consider two of them fair exchange for a wife any day. A pair of them can pull down a gazelle or jackal. They scent their quarry as far as eighty yards away. While hunting, they wear wooden bells around their necks, so the natives can follow them through the tall elephant grass. They were palace favorites at the courts of ancient Egypt, as evidenced by rock engravings of Basenjis seated at the feet of Pharaohs (circa 2300-4000 B.C.) which have been preserved, or were preserved, in the Egyptology Department of the British Museum. The breed fell into obscurity for a good many centuries, but in 1895 a pair were shown in London. These died of distemper, and no Basenjis appeared again in England until 1932, when several were imported from the Sudan. By 1937, a Basenji fad was under way in England, and the English Kennel Club officially classified them as a sporting breed. Three generations have now been bred in England, and four months ago, in Ontario, Kiteve and Kikuku gave birth to five and four pups, respectively. The only Basenji resident in the United States at present belongs to Byron H. and Olga H. Rogers of Poundridge, who have him kennelled on the outskirts of Boston. Male Basenjis are firm creatures and rule the house; a bitch, for example, wouldn't dream of eating until the male has finished. Basenjis are affectionate, especially with children, and generally remain quiet, except during the mating season, when they engage in continuous oodling.

Lang had no idea whether their throat structure differed from that of other dogs, so we dropped a line to Dr. Richmond in Canada on this point. He promptly replied that he didn't know, either, why the dogs are barkless but suspected that their vocal cords have atrophied from generations of silent hunting. He said that Basenjis delight in tracking down reed rats, vicious, long-toothed creatures weighing about twelve pounds, and that one essential of a reed-rat hunt is absolute silence. Dr. Richmond also said that he intends to take the matter up with someone at the University of Toronto, hoping to get some light on the subject.

AUGUST, 1941

Finance

* * *

Last week we felt dizzily like a party to some of Wall Street's deeper complexities when we called in at the offices of Merrill Lynch, E. A. Pierce & Cassatt the afternoon that firm amalgamated with Fenner & Beane to form the largest brokerage-and-investment house in the United States--Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Beane (please don't ask us what happened to Cassatt), ninety-three offices in ninety-one cities and membership in twenty-eight security and commodity exchanges. This merger was the culmination of a series of earlier ones, beginning in April, 1940, when Merrill Lynch consolidated with E. A. Pierce & Co. and Gassatt & Co., forming Merrill Lynch, E. A. Pierce & Gassatt, which last May absorbed Fuller, Rodney & Co., Banks, Huntley & Co., and three offices of Sutro Bros. & Co. The idea of people having to make out checks to Merrill Lynch, E. A. Pierce & Cassatt, Fuller, Rodney, Banks, Huntley, and three offices of Sutro Bros. & Co. was apparently too much for all concerned, so several of the names disappeared, like Cassatt. We never did find out what happened to Cassatt.

We finally found Mr. Robert Magowan, one of the new firm's sixty-seven partners, an old Merrill Lynch, etc., man who kindly took us in hand and explained that if a considerable amount of confusion seemed to exist, it was mostly because of the job of legally transferring customers' securities to the new firm. Under Stock Exchange regulations, some partner or other had to sign personally all of the stock certificates around the consolidated place, and there were three hundred thousand certificates. "Damn nonsense," said Magowan. Most of the signing had been done over the weekend preceding our visit, twenty-one partners having been rounded up on verandas and in locker rooms and put to work. A number of them heroically sat and affixed their signatures for twenty-one hours. Some of the men working in the defense industries should have seen them. "Allen Pierce and Alph Beane were down," said Magowan, referring to members of the High Command. He added that Merrill was away from these parts on vacation and that Fenner was in New Orleans. Lynch is dead. The high-voltage penmen knocked off for lunches and to refill their pens occasionally, and some of them listened with one ear to a Dodgers broadcast.

We expressed our regret at not having seen the partners at work and Magowan took us into one of the rooms on the chance that some of them might still be in action. "Any partners here today, Joe?" Magowan asked a clerk. "Yep, two," said the clerk, pointing out a pair of earnest, elderly gentlemen wearing straw hats and doggedly signing away at a bookkeeper's desk in a corner. They glanced up briefly at Magowan. "Sorry, but you can't sign these," one of them said. "O.K.," said Magowan. "Fenner & Beane people," he whispered. Naturally, not all of the partners know each other yet, and sooner or later the largest brokerage house in the country is going to do something to prevent their brushing by each other in the halls without nodding: a series of cocktail parties during the winter, or something. Five hundred rubber stamps with the new firm name were on order at the time of our visit and are to be distributed to big customers for convenience in check-writing. As for the telephone operators, they have been instructed for the time being to greet all callers with the full, pulsating name, "Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Beane."

JUNE, 1944

Notes on Freedom

* * *

For our money, the most impressive moment in the I Am an American Day ceremonies in Central Park a couple of Sundays ago was a brief speech by Learned Hand, senior judge of the United States Circuit Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit (New York, Connecticut, and Vermont). Next day not a newspaper in town quoted his remarks, so we went down to the United States Courthouse on Foley Square to get a copy from the Judge himself. He is a rugged, stocky man of seventy-two, with bushy eyebrows. During our call he evidenced a tendency to prowl around his chambers, which are approximately half the size of the Grand Central waiting room. "Three or four people have called me about the speech," he said. "I'm glad they liked it." He handed us a typescript and we will quote some excerpts, with the wish that we had space for more: "Liberty lies in the hearts of men and women; when it dies there, no constitution, no law, no court can save it; no constitution, no law, no court can even do much to help it.... The spirit of liberty is the spirit which is not too sure that it is right; the spirit of liberty is the spirit which seeks to understand the minds of other men and women; the spirit of liberty is the spirit which weighs their interests alongside its own without bias; the spirit of liberty remembers that not even a sparrow falls to earth unheeded; the spirit of liberty is the spirit of Him who, near two thousand years ago, taught mankind that lesson it has never learned but has never quite forgotten: that there may be a kingdom where the least shall be heard and considered side by side with the greatest."

Judge Hand told us that all his decisions and speeches are written in longhand, frequently after hours of intense struggle. "For me, writing anything is like having a baby," he said. "I take long walks through the park and think and think before putting down a word. I don't deliver a speech to the trees, like Roscoe Conkling, or anything like that. Never dictate. Can't get the hang of it. But I've written countless thousands of words, and the Definitive Hand," he said, pointing to the bookshelves, which lined the room from floor to ceiling, "is along those walls. Mighty dull stuff."

Judge Hand feels that latter-day oratory has taken a turn for the worse. "Too many people have other people write their speeches," he said. "Why, just the other night I was sitting on the dais with the waxworks at some banquet and a fellow rose and made some intelligent introductory remarks. Then he reached into his pocket, pulled out a paper, and said, `I paid fifty dollars for this speech, so I better deliver it.' I ducked out." Judge Hand said that when he was a boy up in Albany, orators were the most envied personages in town. "There wasn't much theatre or music in those days, so the orator satisfied everybody's yearning for drama," he went on. "The orators talked a good deal of fustian--lots of Webster is fustian, for example--but they were creative and did their own writing and nobody much cared what they said." He had little traffic with Fourth of July speeches when he was young, concentrating instead on firecrackers, but his cousin, Judge Augustus Hand, who is also a colleague on the bench, took a more serious attitude toward Independence Day. He used to go out in the fields with his sisters and together they would read aloud the Declaration of Independence.

The maiden name of the Judge's mother was Learned; hence his first name. Few people can resist calling attention to its relevancy in his case. For instance, when President Conant of Harvard presented him with an honorary degree some years ago, the citation read, "A judge worthy of his name, judicial in his temper, profound in his knowledge, a philosopher whose decisions affect a nation." Judge Hand has been on the Circuit Court of Appeals since 1924; for fifteen years before that he was a judge in the Federal District Court, Southern District of New York. Lawyers don't seem to mind much when cases of theirs are lost by reversals on appeal if the reversal is made by Judge Hand, and jurists rank his decisions with those of Holmes and Brandeis. His remarks in Central Park were a simplification of many earlier speeches and a lifetime of thought. "Democracy can be split upon the rock of partisan advantage," he told us. "Believe me, if majorities in legislatures pass bills merely to press their advantage and say, `Let the courts decide; liberty will not be preserved in the courts, it will be lost there." Judge Hand moved to the window and looked down on Foley Square. "I believe Holmes felt that way," he said.

(Continues...)

Copyright © 1999 Philip Hamburger. All rights reserved.