| Author's Note | |

| Introduction | |

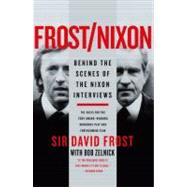

| Frost/Nixon | |

| The Deal | p. 3 |

| The Interviews | p. 27 |

| Prime Time | p. 133 |

| The Road Back | p. 155 |

| Reevaluating Nixon | p. 185 |

| Taking My Leave of Richard Nixon, May 1977 | p. 203 |

| Transcripts | |

| Watergate | p. 209 |

| The Huston Plan | p. 253 |

| Chile | p. 275 |

| Vietnam | p. 295 |

| Kissinger | p. 353 |

| Table of Contents provided by Blackwell. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

The Deal

"It will be a sort of intellectual Rocky."

The speaker was the writer Peter Morgan, and the time was January 2004. Peter and his producer, Matthew Byam-Shaw, had come to my office to talk about their idea for a stage play, to be called Frost/Nixon, which would tell the story of the Nixon interviews and Nixon's dramatic mea culpa in 1977.

They had three main requests. First: As the holder of the rights, would I give them permission to go ahead with the project? After some discussion, I said that, in principle, I would. That led to the second request: Would I let them have these rights for nothing? Peter and Matthew are both charming and persuasive, as you can tell by the fact that I said yes to this request. Frost/Nixon, they hoped, would open at the Donmar Warehouse in London and hopefully transfer into the West End. I said that my free grant of rights would extend to both these eventualities but not to any further manifestations of Frost/Nixon.

Oddly enough, it was not the money, it was the third request that gave me the most pause. Peter said that they both thought that Frost/Nixon would have more credibility if I had no editorial control. That was more difficult, and I said that I needed time to think about it.

It was a couple of months later before I gave them the green light on this issue. I felt very fifty-fifty about it at the time because I would be entrusting a project that was very precious to me to third parties. On the other hand, they felt that the play would get a better hearing if it were independent of my or my company Paradine's editorial control. In the end, I decided that the advantages probably just about outweighed the disadvantages, though when I saw the first draft, I was not so sure. Later drafts upset me less. I think that was because they were an improvement, or maybe I was just getting inured to the experience!

It is a curious feeling to go to the theater and watch yourself onstage—particularly if the "Frost" character is depicting some of the most dramatic episodes of your life. They were events that had taken place thirty years before, but somehow it did not feel that way. Peter had promised that he could make these events seem relevant, even current, and he had achieved that.

I attended a preview of Frost/Nixon two or three nights before the play opened in August 2006. I thought it was brilliantly written, directed, and acted. There were more fictionalizations than I would have preferred, although one such piece of fictionalization—Nixon's phone call to me on the eve of Watergate—was, I thought, a masterpiece.

I was not so sure about some of the other fictionalizations. Why was Watergate now the twelfth of the twelve sessions and not—as actually happened—two sessions in the middle, at sessions eight and nine? Why did James Reston's discoveries from the Watergate tapes only reach me on the morning of the Watergate session and not eight months earlier, as had actually been the case? Why did the early sessions, which contained a lot of good material, have to be depicted so negatively? Why do we see Swifty Lazar, Nixon's agent, making a series of demands without learning that they had been successfully rejected? Whenever I made these points to Peter, he would simply sigh and say, "David, you've got to remember this is a play, not a documentary." However, aware of my concern, he thoughtfully added an author's note to the program, making the point that he had sometimes found it irresistible to let his imagination take over.

And the play was an instant hit. The rave reviews were unanimous and Peter, the director, Michael Grandage, and both Michael Sheen ("Frost") and Frank Langella ("Nixon") were deservedly saluted.

Frank Langella did not look like Nixon, but he was Nixon. "I have never been a Method actor," he told me. "Normally, when I'm offstage during a Broadway play, I chat to the stage manager about how the Mets are doing or whatever, but with this play, the tension is such that I did not want to go out of character, even for a minute, when I was offstage. I would go to the darkest corner at the back of the stage and just stay with my thoughts and wait. When I was required, the stage manager had to come over to me and say, 'Mr. President, you are needed onstage.' "

I met Michael Sheen for the first time after attending that preview. The cast had not been told that I was there. Michael said that they were all bewildered because for the first twenty minutes the audience seemed nervous and there was less response than usual. I don't know whether people expected me to leap up and say, "Stop! That's not true!"

When I interviewed Michael last December, shortly after the Broadway production and the film had been announced, Michael said, "I'm going to be playing David Frost for the next year."

"That's a coincidence," I said. "So am I."

How did the Nixon interviews come to pass in the first place?

Well, I must say that as I look back now, I marvel at the fact that we managed to pull them off. There were so many obstacles and challenges to overcome.

First, there was the challenge of getting Richard Nixon to say yes.

"Don't waste your time," said an Australian, adding cheerfully, "you've got Buckley's"—a piece of Australian vernacular intended to make a lost cause seem roseate by comparison.

"In the words of David Schoenbrun, talking about a possible interview during World War Two," I replied, " 'let de Gaulle say no.' "

I knew from experience that getting a clear response—whether yes or no—would not be easy. Experience came from The David Frost Show. Following the interview with then . . .

Frost/Nixon

Excerpted from Frost/Nixon: Behind the Scenes of the Nixon Interviews by David Frost

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.