Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

When they were close enough to touch bottom with their paddles, the people poured out of the nearly swamped canoes. The grown-ups held little ones and the little ones held even smaller ones. There were so many people jammed into each boat that it was a wonder they had made it across. The grown-ups, the ones who wore clothes, bunched around the young. A murmur of pity started among the people who had gathered on shore when they heard Omakayas's shout, for the children had no clothing at all, they were naked. In a bony, hungry, anxious group, the people from the boats waded ashore. They looked at the ground, fearfully and in shame. They were like skinny herons with long poles for legs and clothes like drooping feathers. Only their leader, a tall old man wearing a turban of worn cloth, walked with a proud step and held his head up as a leader should. He stood calmly, waiting for his people to assemble. When everyone was ashore and a crowd was gathered expectantly, he raised his thin hand and commanded silence with his eyes.

Everyone's attention was directed to him as he spoke.

"Brothers and sisters, we are glad to see you! Daga, please open your hearts to us! We have come from far away."

He hardly needed to urge kindness. Immediately, families greeted cousins, old friends, lost relatives, those they hadn't seen in years. Fishtail, a close friend of Omakayas's father, clasped the old chief in his arms. The dignified chief's name was Miskobines, Red Thunder, and he was Fishtail's uncle. Blankets were soon draping bare shoulders, and the pitiful naked children were covered, too, with all of the extra clothing that the people could find. Food was thrust into the hungry people's hands—strips of dried fish and bannock bread, maple sugar and fresh boiled meat. The raggedy visitors tried to contain their hunger, but most fell upon the food and ate wolfishly. One by one, family by family, the poor ones were taken to people's homes. In no time, the jeemaanan were pulled far up on the beach and the men were examining the frayed seams and fragile, torn stitching of spruce that held the birchbark to the cedar frames. Omakayas saw her grandmother, her sister, and her mother, each leading a child. Her mother's eyes were wide-set and staring with anger, and she muttered explosive words underneath her breath. That was only her way of showing how deeply she was affected; still, Omakayas steered clear. Her brother, Pinch, was followed by a tall skinny boy hastily wrapped in a blanket. He was the son of the leader, Miskobines, and he was clearly struggling to look dignified. The boy looked back in exhaustion, as if wishing for a place to sit and rest. But seeing Omakayas, he flushed angrily and mustered strength to stagger on ahead. Omakayas turned her attention to a woman who trailed them all. One child clutched her ragged skirt. She carried another terribly thin child on a hip. In the other arm she clutched a baby. The tiny bundle in her arms made no movement and seemed limp, too weak to cry.

The memory of her poor baby brother, Neewo, shortened Omakayas's breath. She jumped after the two, leaving the intrigue of the story of their arrival for later, as well as the angry boy's troubling gaze. Eagerly, she approached the woman and asked if she could carry the baby.

The woman handed over the little bundle with a tired sigh. She was so poor that she did not have a cradle board for the baby, or a warm skin bag lined with rabbit fur and moss, or even a trade blanket or piece of cloth from the trader's store. For a covering, she had only a tiny piece of deerskin wrapped into a rough bag. Even Omakayas's dolls had better clothing and better care. Omakayas cuddled the small thing close. The baby inside the bag was bare and smelled like he needed a change of the cattail fluff that served as his diaper. Omakayas didn't mind. She carried the baby boy with a need and happiness that the woman, so relieved to hand the baby over, could not have guessed at. Having lost her own brother, Omakayas took comfort in this baby's tiny weight and light breath. She would protect him, she promised as they walked. She would keep him company and give him all the love she had stored up but could no longer give to her little brother Neewo.

The baby peered watchfully into her eyes. Though tiny and helpless, he seemed determined to live. With a sigh he rooted for milk, for something, anything. Anxiously, Omakayas hurried toward the camp.

The angry boy with the long stick legs and frowning face sat next to Pinch by the fire. He glared up when Omakayas entered the clearing, but then his whole attention returned to the bowl of stew in his hands. He stared into it, tense as an animal. He tried without success to keep from gulping the stew too fast. His hands shook so hard that he nearly dropped the bowl at one point, but with a furious groan he righted himself and attained a forced calm. Straining to control his hunger, he lifted the bowl to his lips and took a normal portion of meat between his teeth. Chewed. Closed his eyes. When Omakayas saw from beneath one half-shut eyelid the gleam of desperation, she looked away. Not fast enough.

"What are you staring at?" the boy growled.

"Nothing."

"Don't even bother with her," said Pinch, delighted to sense an ally with whom he might be able to torment his sister. "She's always staring at people. She's a homely owl!"

"Weweni gagigidoon," said Angeline, throwing an acorn that hit Pinch square on the forehead. She told her brother to speak with care, then commanded him, "Booni'aa, leave her alone!"

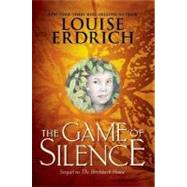

The Game of Silence. Copyright © by Louise Erdrich. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved. Available now wherever books are sold.

Excerpted from The Birchbark House by Louise Erdrich

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.