|

9 | (2) | |||

| Acknowledgments | 11 | (2) | |||

| Introduction | 13 | (16) | |||

| Cast of Characters | 29 | (4) | |||

|

33 | (14) | |||

|

47 | (14) | |||

|

61 | (20) | |||

|

81 | (36) | |||

|

117 | (38) | |||

|

155 | (38) | |||

|

193 | (16) | |||

| Appendix I: Sexual Superstitions Through Time | 209 | (2) | |||

| Appendix II: Animal Superstitions Through Time | 211 | (10) | |||

| Further Reading | 221 | (4) | |||

| Index | 225 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

In the Beginning

All scientific knowledge that we have of this world, or will ever have, is as an island in the sea of mystery. We live in our partial knowledge as the Dutch live on polders claimed from the sea. We dike and fill. We dredge up soil from the bed of mystery and build ourselves room to grow.... Scratch the surface of knowledge and mystery bubbles up like a spring. And occasionally, at certain disquieting moments in history (Aristarchus, Galileo, Planck, Einstein), a tempest of mystery comes rolling in from the sea and overwhelm our efforts.

--Chet Raymo,

Honey from Stone: A Naturalist's Search for God

The real power of Mary Toft--whether it lay in her ability to convert a human fetus into an animal, to provoke sexual desire, or to make a man a fool--was to draw man lower than he was, to make him a beast in some way, to transform him downward to the body.

--Dennis Todd, Imagining Monsters

When the stars threw down their spears

And water'd heaven with their tears,

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the Lamb make thee?

--William Blake, "The Tyger"

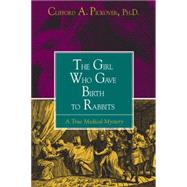

Mary Toft gave birth to her first rabbit in October of 1726. Soon a nation would be enthralled, prominent medical men would be baffled, and even King George I of Great Britain would demand an official investigation. Although the king would die the following year, he would live to understand the full extent of this medical enigma.

I can hear you wondering out loud. How did she do it? Doesn't it violate the laws of science? Was it a hoax? Could it be her baby was a human child with a birth defect giving it rabbitlike features?

Let's set the scene. Imagine yourself transported to the rustic village of Godalming in the county of Surrey, England (figure 3). Today, Godalming is full of churches with twisted spires, timbered buildings from the 1800s, and narrow streets, most of which can be negotiated by a small car. Situated south of London in the valleys of the rivers Wey and Ock, Godalming was first mentioned in King Alfred's will in 880 C.E. By 1086, the village was relatively affluent. The town prospered during the Middle Ages, and by the sixteenth century Godalming became a center of the wool and cloth trade. Business flourished through the Elizabethan times up to the 1700s, when foreign competition intensified and made life more difficult for the citizens Godalming.

About twenty years after Mary Toft gave birth to rabbits, the main road from London to Portsmouth opened--making Godalming a convenient stopping place. In 1881, Godalming became the first town in the world to have a public electricity supply.

Continue to imagine you are there today. Look around you. Smell the fresh honeysuckle and lavender. From the town, across the River Wey, you can see bright green meadows known as the Lammaslands. Following the river north you come to the tranquil Catteshall Lock and Farncombet House where all manner of boats are available for hire.

The year is 1726. Imagine twenty-five-year-old Mary Toft, the heroine of our strange story. She's been married to her husband, Joshua, for six years. Of their three children, two are still alive. Their names are Mary and James. Anne, who was born in March 1723, died four months later from smallpox. James is two and was born in July 1724. His sister Mary's exact date of birth is unknown. The following family tree should help clarify this.

The Toft Family Tree

The Toft ancestors had lived in bucolic Godalming since the early 1600s, and most of the generations had made a good living in the woolen trade. However, by the 1720s the Tofts were living in harder times. Mary's husband, Joshua, was a poorly paid laborer who was hired to cut and finish cloth. As an unsuccessful journeyman clothier (cloth-worker), Joshua didn't have the money for his family to live in high style, eat good food, or have the fancy clothes of earlier Tofts.

The literature describes Mary as being short, stout, with coarse features, and of a "stupid and sullen temper." However, you should take such reports with a grain of salt because they may be colored by eighteenth-century attitudes toward unsophisticated women (figure 4). Nathanael St. André, a surgeon from London, said she had a "fair complexion," and "seemed to be of a healthy, strong constitution." In any case, Mary had to have great mental and physical perseverance to survive the hell about to befall her in the hands of medical men and lecherous Londoners. The scrutiny and anger of England would be on her in full force.

Imagine yourself only a few feet away from Mary, watching her as she works in the hop fields, earning a few pennies a day, wishing there were some way out of her poverty. Her back is tired, her hands and feet are sore. The air is filled with the lusty odors of earth and sheep manure. In the distance is the gentle tintinnabulation of cow bells.

Mary's story starts in April 1726 when she was five weeks pregnant. She says she saw a rabbit hop in front of her while she was weeding the garden. She followed it, but it quickly escaped. That night she awakened in a sick fit after dreaming she was in a field with rabbits in her lap. For the next several days, she had an intense desire for rabbit meat--a craving she could not satisfy without the money to buy rabbits at the market. Her desire was so strong that she believed it influenced her reproductive organs. Here is how the 1726 poem "The Doctors in Labour" described it:

When I [Mary Toft] five weeks was gone with Child,

And hard at work was weeding in the field,

Up starts a rabbit--to my grief I viewed it,

And vainly though with eagerness pursued it,

The effect was strange--blest is the womb that's barren

For that can near be made a coney [rabbit] warren.

The rabbit all day long ran in my head,

At night I dreamt I had him in my bed;

Me thought he there a burrow tried to make

His head I patted and stroked his back.

My Husband waked me and cried [Mary] for shame

Let go--what was meant I need not name.

In August, Mary suffered a miscarriage. She had abdominal pains and a "large lump of flesh" emerged from her birth canal. Mary described it as "a substance as big as my arm, a truly monstrous birth." Scholars believe her miscarriage was real.

On September 27, Mary had tremendous abdominal pains. She grabbed at her belly and began to shake.

"Get Mary Gill!" Mary Toft yelled. Mary Gill rushed over and found her neighbor writhing in great pain. Mary Gill heard and saw a monstrous birth product fall into a pot between Mary's legs. Mary Gill didn't have the time or stomach to study the baby; however, scientists later inspected the "baby" and found it resembled a liverless cat with the backbone of an eel perched inside its intestines!

Mary Gill ran from the house to send for Ann Toft, Mary Toft's mother-in-law and a midwife.

The Toft family gathered around Mary. How could this strange birth happen? Soon, other neighbors came to observe the strange baby. The Tofts decided it was time to consult a medical person of more experience, and they sent the remains of Mary's child to John Howard, Guildford's respected "midwife" and obstetrician. He had been practicing midwifery and surgery for more than thirty years. When Howard studied the monstrous child, he was at first suspicious, then apprehensive. Howard came to the Toft home the next day to see Mary Toft.

"Look at this!" Ann Toft said as she showed Howard some more pieces of a cat that she had taken away from Mary in the night. The neighbors said they witnessed the actual birth.

As Mr. Howard looked between Mary's legs, his sense of horror deepened. Several other parts, perhaps from a pig or cat, came from her womb with the aid of Ann Toft. Howard was unsure of what to make of the astonishing births and so remained the entire day with Mary. Perhaps he suspected a hoax. "I will not be a true believer," he said, "until I deliver something from Mary myself ." The next day he returned and delivered more cat parts by himself. In spite of this, he was not convinced that the births were genuine. Howard turned to the Tofts. "I'll not be convinced until I deliver the monster's head ."

There was a relative calm in the Toft house for two weeks, but this was just the eye of the hurricane. In the first week of October, Howard helped Mary deliver a rabbit head while Mary bled profusely.

With the delivery of the head, Howard began to accept her story. It had to be real. And from then on, there was no stopping Mary. Over the next few days, dead rabbit after rabbit came from between her legs. Many times the rabbits were torn into several pieces before leaving her womb. By early November, she was delivering nearly a rabbit a day. Howard gave Mary a little money to help her during these difficult times.

It didn't take long for Howard to become very involved and excited by these miraculous births. Who wouldn't? Imagine yourself called to a neighbor's home to witness monsters falling from a woman in labor. How would you react? Howard wrote enthusiastically about the births to friends, to respected physicians, and to noblemen. Every time Mary delivered, Howard felt bizarre movements in her belly that he attributed to fetal rabbits squirming through her uterus and Fallopian tubes.

Now that Howard had let the cat out of the bag, so to speak, the entire town became excited by the wondrous births. Huge crowds came to Mary's modest home to see her eerie "children," which Howard preserved and displayed in shiny bottles. After Mary gave birth to her eleventh rabbit carcass, Howard decided it was time to let the entire country know. He offered to present two of her rabbit-babies to England's Royal Society. He wrote to the secretary of King George I:

As soon as the eleventh rabbit was taken away, up leapt the twelfth rabbit, which is now leaping. If you have any curious person that is please to visit, he may see another leap in her uterus and shall take it from her if he pleases.

Howard had turned from a skeptic into a true believer. One reason for his conversion was the current popular notion that prenatal influences could drastically shape a fetus. He thought Mary's story of craving rabbits played a role in producing strange infants. In addition, Mary's neighbors were convinced that the births were authentic, which helped shape Howard's observations and opinions. And then there were the signs of pregnancy: the bleeding and the powerful abdominal contractions, the snapping sounds from within her womb, and the unpretended pain. Could these be remnants of her August miscarriage? Howard was not sure, but he enjoyed the notoriety he received by being the discoverer of the miraculous births. The fact that he personally delivered rabbits from her vagina and could detect no hoax was probably the biggest factor in his conversion. (Imagine how you would feel if you delivered the pieces--would your first thought be of a hoax?) Howard reported:

When she delivered one rabbit, another was immediately felt in her belly, struggling with such violence that the motion thereof could be sensibly felt and seen: That this motion has sometimes been so strong as to move the bed-clothes, and that it has lasted for twenty and above thirty hours together.

How do you think today's press would handle such a story? Would Mary Toft be on 60 Minutes, Oprah , or 20/20? Would the newspapers garble her story? In Mary's time, news of the strange births spread across London, and on October 22, an inaccurate, distorted story was printed in the British Journal :

They write from Guildford that three women working in a field saw a rabbit, which they endeavored to catch, but they could not, they all being with child at the time. One of the women has since, by the help of a man midwife, been delivered of something in the form of a dissected rabbit, with this difference, that one of the legs was like unto a tabby cat's, and is now kept by the said man Midwife at Guildford.

The amazing births caused quite a royal stir, and even King George I became intrigued. He immediately ordered Samuel Molyneux, secretary to the Prince of Wales, to find out whether the births were authentic or merely some clever hoax. Court anatomist Nathanael St. André was to accompany Molyneux, who was a clever but amateur scientist and a fellow of the Royal Society. Molyneux's knowledge of telescopes was great, but of medical matters he knew little.

Copyright © 2000 Clifford A. Pickover. All rights reserved.