What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, June 16, 1842

We buried him this morning, but the shock of his death pulls me back through the decades where I wander unbidden through every moment of the years we spent together on the banks of the Mississippi river. I see the prairie swept purple with coneflower, I find myself upon the soft grass of the peninsula, and it is difficult to pull myself back to my duties, to my son and to this place. The house is dark, but for the taper light, and the quiet is broken by the dispirited groan of his spaniel, who looks to me for reassurance I cannot offer. How is it possible that my love is not sleeping in the next room? I rise to search for him but find only a cold silence over our bed.

After the funeral service, the widow James pressed a speckled hand against my cheek and whispered to me, "Now he is gone, you must pacify yourself with living as though your footsteps have never marked the earth." Her words have wisped around in my mind since she said them, slighting words, and if this is Mrs. James's way of comforting the grieving, she can keep her comfort. My sorrow is born of my wound, for with his death, my soul has been halved.

On spring evenings such as this, we would walk together through the hickory grove and talk for hours of the people and the times we had known together. He would take me in his arms, but look wistfully past me at the river, toward the north, and he would say to me, "I believe the work of the living is the retelling of memory. A thread not to be broken." And knowing what he said to be true, I awoke this morning, having slept beside him one last time. I looked down upon his silent countenance and dreaded the task before me.

I would have to begin the work of remembering.

But when I try to impose order on my memories, I cannot find sequence, nor am I able to prompt a beginning. Even now, I begin to drift back, but only to the evening before this one, when I undressed him and bathed him. He lay so quietly, his lips parted and his head tossed back. His coat smelled of bran, there were marks where the dust had been beaten from the seams. I forced the brass buttons through their grommets, and the wool placket felt thick in my hands. When I peeled it back, the sight of his broadcloth shirt bearing the marks of the iron made me believe he would wake to me. A dead man would not worry whether his shirt was neatly ironed.

"Wake up, Henry. You always were a promiscuous napper. Wake up, now."

Something crisped when I opened his coat. I was watchful of him as I slipped my fingers into the pocket and removed the piece of foolscap, creased into fours. I pressed my nose to his dark hair as I unfolded the paper. The letter was penned in his hand -- cruel slashes over the t's, bold down strokes, neat spacing. It was dated June 11, 1842. There was no salutation.

I received your message and was both shocked and perplexed by it. As for myself, that memory haunts me -- indeed it has shaped my years in aspects I have yet to comprehend. But this explains why I was never asked questions that I would have welcomed and perceived as natural, yet I too am guilty of reticence, for I never volunteered a single word. I am glad you have told me. How could you question whether I would come to you? Ever I shall come to you, know that I shall always honor a request from you. In youth and dotage we have shared that which no

And there the letter ended. I let it flutter onto my lap and opened the buttons of his shirt. I sat beside him on our bed with my hand to his breast, regarding those written words once again and then the broad bones of his face. My stomach soured and churned. Though I sat awhile, and tried to trick the knot of his letter apart, the skeins remained tangled. This was the way of him, to leave me mired in place under the burden of his deceptions, committed with honorable intentions, of course.

I picked the letter from my lap and placed it under his hand in the hope a revelatory dream would come to me. It would be a dream wherein I would forgive him his trespasses, and the General, finding comfort in death, would finally speak the truth to me. Wouldn't I be foolish to wait for such a thing? I've always known that it was my charge to venture forth as a self-possessed woman and seek the truth for myself. Until I did, years ago, I had become adept at subsisting on his assurances.

Ever I shall come to you...who had inspired my husband to pen words resonating of such urgency and discretion? It could be a letter to anyone. Anyone at all. But not to me. In all the years of our marriage, he never spoke so floridly to me. I snatched the letter out from under his hand, crumpled it, then tossed it upon the chest of drawers.

The General's limbs were corded from a hard life, and few would have guessed him to be fifty-nine. I cupped the arches of his bare feet in my hands and watched the water sparkle as it dripped from his heels.

I took great care not to touch his toes.

My servants touched the toes of the dead to keep them from turning ghostly. I wanted the General to come back and haunt me. I cradled the hope of it. I lay beside him after he died, not feeling a bit of peculiarity in it for he was my husband, gone a little bit chilly is all. In the night, I kissed his face, and his skin felt like cooled paraffin against my lips.

"It is safe now to talk of it, Henry, you can tell me now. There is no one here but the two of us. You can tell me everything, and I shall not reproach you."

The hair of his chest was dark and curly with a few gray strands. I squeezed the rag into the basin, soaped the rag with my own lavender soap, not the laundry soap made of lye and ashes. The water left a silty line in the hollow of his ribs. My breath caused the brown air to dance about me as I pulled the brush through his hair. Then I scraped the flesh from under his fingernails. With small, even steps, I crossed to the bed stand and burned the tiny mound of it in the taper flare.

With a fresh cloth and salt water, I cleaned blood having the texture of coffee grounds from the General's teeth, patting his lips to let him know I had finished. And when he was free of his clothing, I let him lie there a while, as if he were napping on a heavy July afternoon, sleeping with no hope of a cool breeze. Innocent and naked. I saved the Spanish milled coins until the moment the soldiers put him into the box, and that was the worst of it; placing death weights on his beautiful eyes. But, I would not let the camp surgeon knot a winding sheet about his limbs. My husband lived freely on this vast Western landscape. How then, could I allow them to restrain him for all eternity?

The General has been gone two days from me. I held him as he passed, rather selfishly, I suppose, I wanted him to speak of our recent reconciliation, I wanted him to tell me that I had always been vital to him. But that was not his way. He stared off as his breath became shallow, and he thought instead of his place in the next world. "Beyond forgiveness," he murmured, and then...he slipped off so quietly, I asked after him..."Husband?"

Late last evening, the Sauk, Winnebago and Maha Peoples settled in the center of the barracks esplanade to set up their tipis. The wind blew the sound of clattering lodge poles through my open window, I could hear the Indians speaking to one another as they prepared to make their last visit to the General. And this morning, citizens of St. Louis chartered the steamerLebanon, then disembarked at the landing, a grim cloud lofting and rippling up the hillside. There were politicians and matrons, shopkeepers and a volunteer force of militia from outlying counties, half drunk at midmorning from their breakfast of crackers and whiskey, all filled up with false sentiment for a general they did not know.

Those militiamen did not know my husband, nor would he have cared to make their acquaintance. The General learned during the wars of the thirties that having the militia along on campaign would surely doom the effort. They were dirty and unkempt. I know he would have despised the look of them. But the regular troops had been ordered to Florida to fight the Seminole, so the barracks were deserted, and my husband deserved an honor guard, even a pitiable one. In his last year, my husband was a general without troops.

As the Reverend Hedges read the service, my veil formed a shield around me, dropping to my toes so I appeared as a sniffling black bell jar to the other mourners. It wasn't that I wanted the privacy to cry, such a thing hasn't been possible since he left me. Crying seemed too small a grace to the worst event of my life. Now and then, the crowd would shift under the long winds blowing up from the river and right themselves when a scuddering cloud crossed the sun.

The regimental band played "Roslin Castle," a dirge the General disliked, then the militiamen shrieked, causing everyone to jump, shouted a lament and poured bottles of mash in the dirt mounded round the grave. They sang a ragged a cappella version of "Mo Ghile Mear," "Our Hero," then fell to weeping upon one another. I know my husband would have been bemused by the exertion of this false grief on his account.

I closed my eyes and imagined him near me, sheltering me with his arm, and I wondered what was left for me beyond his memory. I was discouraged by what I conjured, for the years to come were entirely too dark to be seen through. I felt vanquished, I believed I could tolerate no more of this ceremony. But then I was distracted from my reverie by the sight of the General's bay.

Now, as I simply couldn't fathom the General flourishing in the afterlife without his horse, I had asked a Maha warrior to perform a ritual common to his people at the burial ceremony. Billy, our groom, led the General's horse around to stand before the assembly. The warrior stepped forward, said something none of us understood, then wrapped a hemp loop around the animal's neck and strangled it with grace and ease.

A horrified gasp went up from the crowd, and the militia aimed their Harper's Ferry rifles at the Indians standing opposite me. I jumped before their guns, explaining that this honor had been performed at my request. While the crowd settled, I overheard ugly mention of the red men who had come to pay their respects.

The grave looked a slack mouth under the toe of my boot, asking questions none of us dared answer. I leaned forward, pinioned by Senator Benton on my left and Colonel Stephen Kearny on my right. They held tight to me as if I were a bedlamite contemplating escape. My veiled glance sent the mourners to panicked searching of the horizon. When I leveled my gaze upon them, they hurriedly looked away from me. I knew what they thought; they feared my reason had once again slipped under a cloud. Have you seen the Mad Widow Atkinson? they would ask one another.Avoir le diable au corps.A pity. The senator and the colonel tensed, silently willing me to forgo grievous outpouring. They had borne witness at the last burial. Ten years had elapsed, and I hoped they had forgotten what was past, but apparently, they had not.

Senator Benton offered his arm, and we led the cortege to the regimental dining hall for a breakfast, but I do not remember most of what transpired this morning. It was a blur of half-wept condolences and somber greetings. Numbly, I watched the crowd mill about like so many black beetles, emitting a low humming sound. In the corner, watchful and silent, were the Indians, all of them dressed in their best ceremonial wear.

And that is when I saw Bright Sun, rising gracefully with a nod to her companions. My hand flew reflexively to my bodice in a protective gesture, and I peered sidelong at her, under my lashes.

Bright Sun was dressed after the manner of Indian women who live along the rivers, in a red skirt, a calico blouse and, despite the heat, a Hudson Bay three-point blanket over her left shoulder. But she was distinguished by the red star upon her forehead, the "mark of honor" denoting her status as daughter of a war chief. Throughout the morning, we caught the glance of one another, and each of us intuited an unspoken curiosity about the other. It has always been this way between us, scrutinizing, but pretending disinterest. Of course, I knew who she was. Bright Sun was a translator for the Sauk and Fox tribes. But I have never, in sixteen years of sightings, chance meetings and surprising arrivals, been able to discern what she was to my husband.

In late afternoon, the crowd thinned and I took my leave with Colonel Kearny. The silence was thick after the noise of the hall. I was glad for his company but eager to rest, for I was deeply wearied by my sorrow. When I stepped onto the sagging porch of our log house, I glanced over my shoulder and saw a tribal contingent coming toward us. Bright Sun followed a respectful distance behind the warriors, clasping her hands to her waist. Her head was slightly bowed, and her skirts blew elliptically over the grass as she strode along with that vexingly confident posture of hers.

Colonel Kearny opened the door and motioned me across the threshold. I looked back once again at the approaching group.

"The Sauk men go first."

"What?" Kearny asked with a worried look at me.

"I once told the General that I disliked their practice of making the women walk behind the men until he explained that the warriors clear the path of danger for their women."

"Uh-huh. Now, Mary, don't allow company to wear you out. You're not in a form to entertain, so I'll tell Nicholas to urge them along after they've made their condolences."

"Thank you, Colonel, that's very kind of you."

"I'll be leaving now, but you let me know if there is anything you need. May I write to your ma or to your brothers and sisters? They're all in Europe, aren't they?"

"Yes."

"A shame they're so far away at a time like this."

"I'll get along."

"You ask my wife or myself for anything you might need. Don't be proud."

"I'll be fine. You'd best head back to the landing before it gets any darker. I wouldn't want you to miss the steamer. Give my regards to Mrs. Kearny." He placed a chaste kiss on my forehead, then took his leave.

It was much too hot for a fire this afternoon, but Nicholas built one of pine, which I object to mightily, for nothing pops more violently than pine, and I feared the plank floors would catch fire once again. And it would be terribly inconsiderate of me to burn the commanding officer's house just when I am required to turn it over to Colonel Stephen Kearny and his wife.

The Kearnys had not hurried me to vacate, but I sensed their eagerness to "ascend to the throne" and did not begrudge them their happiness. Oh, well, perhaps I did just a bit. It was painful to see my husband's heir apparent, a man very much like the General, preparing to assume command of the Ninth District. This was the cruel truth of military life; a fortnight previous my husband controlled all of the American West. Now that he had died, my son and I were to be tossed out of the only home we have known these past sixteen years.

I walked through our bedroom and opened the wardrobe. The General's uniforms and breeches hung from hooks, his boots were lined up neatly on the bottom shelf as if awaiting marching orders. But I was not prepared for the clean scent of him wafting from his clothing. I turned quickly, expecting to see him quietly about some task in the room with me, expecting him to grin and shrug and assure me that the past few days had been a terrible misunderstanding.

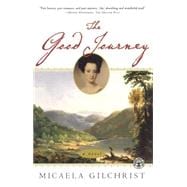

"Henry?" I said aloud, then bent in pain at my folly. When my eyes began to sting, I drew a breath and straightened my back. Though I had been an old bride of twenty-two, I was now a young widow of thirty-seven. A wiser woman, perhaps, would see balance in such a thing. The mirror over the chest of drawers showed me my decay. Well, I must be honest; I was widely considered a beauteous woman and vainly pleased by the popular opinion. I owned a thick mass of dark brown hair and had an oval shape to my face and, when I was nineteen, Thomas Sully of Philadelphia painted my portrait, sipping his Frontignan whilst paraphrasing Herrick. The artist flitted and dabbled, saying, "Mary, oh Mary, I'll kiss the threshold of thy door."

When he went so far as quoting "Upon Julia's Breasts," and rather brashly substituting my name for Julia's, I harrumphed him and marched out of the drawing room. But now, my mourning weeds were a drain to color, my blue eyes were mostly red and my dark hair had been flattened by the weight of my bonnet. "You brazen out the day, Mary Bullitt Atkinson," I said to my reflection.

Having chastised myself, I removed a dimity bag from the top drawer and took my journal into the library. I intended to scribble every bit of spurious gossip I'd heard over the past year to distract myself and thereby waste the hours until dawn. But when I took my seat, I saw the General's letter neatly arranged on the desk blotter. Doubtless, Nicholas had saved it. I crumpled it again and made to toss it into the fire but did not. I dropped it, and chin in hand, puzzled at it.Ever I shall come to you...

I hunched over the journal the General had given me so many years ago, a palm-sized book, bound in calfskin, edged in gold leaf. The nib of my quill made scritching noises as I wrote.

Nicholas, a graying and cranky servant who had come West with me years ago from Kentucky, entered the library with a worried glance and stood silently, waiting for me to acknowledge him.

"They here," he said, finally.

"Please direct them in."

I rose and smoothed my black skirt, pulled the floor-length black veil over my head so that I presented a ghoulish figure. My mind spiraled with anxiety and odd fixations on inconsequential things, an attempt, I know, to control some aspect of my life, any little thing at all. I despaired at the nettles that snaked hairy stalks up through the floor. Those weeds were defiantly rooted, as if telling me I was an intruder on the tallgrass prairie. For sixteen years I suffered every hardship a woman could know, and now I had discovered weeds in my library floor.

I bent to pick the artemisia, and the room was filled with an odor like that of juniper. This is what happened when a house was built of green cottonwood. It warped and withered, and there was not enough lime in the whole of the river country to point the gaps. Over the years, Mama had crusaded the cause of the mercantile class from a distance, had shipped me seventeenth-century French antiques, paintings of Huguenot ancestors, then paid a local seamstress to drape the windows in crimson damask, but still, artemisia grew up wild through my floor.

"Ma'am, the -- " Nicholas patted the air with a worried look and searched for something to call the group, then said, "The chiefs is here. And Miss Me'um'bane the Bright Sun, ma'am."

I glanced up to see a dozen plainsmen enter quietly, then stand in a line while Bright Sun, a small-boned woman, hid behind them. She stepped cautiously away from the hearth. I tossed my veil over my head to get a better look at her. I knew her to be about thirty-three years old.

"Yes, I'd stay away from the fire too, if I were you. Strouding easily catches a spark and you'd torch right up and there wouldn't be a thing I could do to save you."

Bright Sun did not respond but cast her gaze upon my feet. What she found so fascinating there, I did not know, nor did I care. She looked away, not because she was shy or retiring, nor was she intimidated by me. Bright Sun believed avoiding my eyes was the polite thing, under the circumstances. I was not so polite. I feigned a smile to study her. She looked away from my scrutiny, muttering "wado 'becnede," words that I had heard many times these years passing. It meant one who stares, but I could not help myself.

Bright Sun had black hair, broad cheekbones underlayed by a nervous pink bloom and hazel eyes, uptilted and large. The many winters she had quartered within the smoky haze of wickiups and wind lodges had weathered her beyond her years. Her face bore the mysterious impress of several races. She adjusted her blanket and surveyed the room. Despite the crowd of humanity, none of us said a word. They were waiting for me to speak. And so I did. "Thank you for attending today, it would have made the General so happy to know you have come one last time," I said.

Blank stares and blinking.

"Miss Bright Sun, will you translate for us, please?"

I waved her through, and she looked over her shoulder to where she had just been. One of the warriors said something. Bright Sun cleared her throat and spoke, "An'geda said he is happy to meet the General's woman and he knew General Atkinson was going to die because he dreamt of him with snakes creeping into his nose and ears."

I was not quite sure how to respond to this, so I smiled and bowed a little and said thank you. The chief spoke again, and Bright Sun began, "And you may sleep at thehu'thugawith the Burnt Leg People whenever you come north once again on the river."

"How nice. Thank you, An'geda. I shall certainly consider your invitation the next time I come to the territories."

And they turned and filed out as silently as they had entered.

Nicholas and I exchanged baffled shrugs.

I watched my visitors drift away over the grass. When they reached the twilit shade of the oak trees, Bright Sun said good-bye to the chiefs and warriors. She paused uncertainly, glancing up the hill at our family burial ground, then down across the green lawn to the river.

She lifted her skirts and dashed up the hill toward the General's grave.

I felt a jealous catch in my breast and decided to follow her. I stepped out from under the black locust trees the General had planted after I had given birth to our third child. I strode over the grassy hill flowering with copper mallow. The twilight was green, the air was cool, and I held my breath when I saw Bright Sun stop before my husband's new bed. Her visit seemed an affront to the intimacy of the setting. I considered setting up a shout to order her away, but I was curious so instead I waited in the shadow of the tree.

Bright Sun knelt, fumbled at her waist pouch, removed a pair of scissors and cut a hank of her blue-black hair. After lofting it to the wind like a small flag, she plunged the whole handful into the dirt and anchored it there with a little mound. Then she removed a few slender, sharp twigs from her waist pouch and thrust them into her forearms. Blood rilled down her hands into the soil.

Who did she think she was, to mourn the General as if he wereherhusband? I balled my fists and clenched my jaw. I turned away for an instant to gather my wits, then coerced myself into a false calm by reminding myself that once, long ago, Bright Sun tendered a generous favor to me at a time when she knew great suffering. Besides, in the days to come, many strangers were going to knock on my door as I packed up my belongings and prepared to return home to Louisville. They too would ask to visit my husband's grave. Should I excoriate every mourner who dared appear at my door? Talk would ripple through the camp and the city entire that Mary Bullitt Atkinson's reason had once again taken flight. And I did not want to travelthatroad again.

"Miss Bright Sun?" I ventured, stepping out from under the tree.

She turned a peppery look upon me, as if I were the interloper upon my own family burial ground. When I said nothing further, she plucked a willow needle from above her wrist and tossed it into the dirt, then offered without meeting my eyes, "I promised Black Hawk and the others I would come."

Black Hawk.

Even now, I see Black Hawk's apparition, and familiar resentments roil out of my heart. I hear the trade bells jingling along Black Hawk's snakeskin armbands as he stands in the willow thicket behind my house, his eyes boring at me through the darkness. From the day I first met my husband, Black Hawk's specter hovered over us.

"How could you possibly have promised Black Hawk...?"

But Bright Sun continued as if I had not spoken at all, "My people -- the Sauk, the Yellow Earth People -- asked me to burn a fire for four nights to light his way. The General is uncertain, he waits here. He is reluctant to go on. And I wanted to come, after what he did for me...and my daughter. In a way, he was ours too. The General belonged to us in the seasons of war."

Her smug, proprietary tone infuriated me. So I asked, "The willow sprigs. Do they hurt?"

She shrugged and touched a curling spray of leaves splattered with her blood. "Willow is only for warriors who are greatly respected."

"I'm not leaving the General here, you know. You may pretend he was yours for as long as you wish, but I'm taking my husband -- and my other loved ones -- home with me, back to Louisville, as soon as I can arrange passage. I won't leave them in this wretched place."

With a nod, I folded my arms about me and left Bright Sun at the grave. As I walked away, I wanted to create an impression of dignity, but my toe caught a compass-plant root and I stumbled, then blushed at my clumsiness. The cottonwood trees whispered above my head, and the weeds released their musky summer odors underfoot.Henry,I thought,how could you have allowed a visit from her, of all people...and at a time like this.

I entered through the back ell, let the door slam, poured myself a bumper of brandy, then slumped in the General's chair in our library. Dust swirled up from the floor on a column of bronze light, yellowing about me like muddy rivers in the springtime. I brought the glass to my lips and regarded the General's portrait, filling the wall opposite.

He returned my scrutiny with cunning disdain. The portrait was commissioned by his men, the Sixth Infantry, after the Black Hawk War. The General cut an imposing figure. He had dark wavy hair and sideburns that fringed around his jaw. His chin was cleft, his nose perfectly straight, his Scottish complexion ruddy. His shoulders were broad, and he was above medium height, but not so tall as Uncle William or the other Clark men. He presented the traditional stance of handsome men, confident he would obtain whatever he pursued. His white trousers were tucked into his boots. He never wore the plumed chapeau that was part of a General's uniform in the army of this new republic. The General could do as he wished. For twenty-three years he commanded all of the Western Frontier, from Canada to the Red River.

His eyes were portrayed as suspicious under heavy lids. In life, his eyes were intensely blue, vivid with thought and speculation; his were the eyes of a man born of the Enlightenment. The first time ever we locked eyes, I curled my toes, my face colored like a majolica poppy; neither modesty nor false delicacy could compel me to look away from him. He captured my reasoning and my heart in that moment; I felt myself being studied for distinct purposes by his scientific eye. By his pagan eye.

When I was eight years old, my Calvinist governess pinned a drawing of a solitary eye over the nursery hearth. Black tangs radiated from a jet circle at its center; this was the eye of a goat or a reptile. The governess wagged her finger at me, "I know your type, Miss Mary. You are a voluptuary. When you are tempted to give way to your true nature, look up into the eye of God and remember he hates your kind. You must submit humbly until the hour of your death and hope against reason for redemption."

That night, I crept into the dark nursery as the moon haze drifted through the windows, illuminating the eye of God. I removed my nightdress and danced naked before Him, thinking that if I was lost to heaven, I may as well entertain the Lord as I descended the circles of hell, one by one.

I have always been enraptured by the forbidden and unknowable.

From the moment the General took my hand in his, I was captivated by what I could neither discern nor fathom in him. At our wedding, I heard murmuring about the difference of twenty-two years in our ages, about the fineness and surety of an accomplished man being ruler of his domain with a rich and comely young wife at his side. They could not guess at the hours when I ruled, the days when I was sovereign, the months when I governed.

I drained my glass and poured myself another, turning slowly to find him watching me. His father's scabbard was slung low over his left hip, gloves covered the broad spans of his hands. I let the liquor swirl over my tongue as the slanting light glinted around us. He was trapped in the room with me, he was a hant locked into a temple of memory where I was the sole congregant.

Sixteen years ago, when I followed the General away, I had known him for only three days. I reconciled myself then to sleeping with a gentlemanly stranger. How could I have known that years later a stranger would die in my arms?

Perhaps in death I shall know thee.

Copyright © 2002 by 2001 by Micaela Gilchrist

Chapter One

Louisville, Kentucky, January 1826

gThere is no place more unforgiving or colder than a Louisville church on the first Sunday after Christmas, I thought as I navigated my way to our family pew. Despite the clutter of bodies, the air was glacial perfection, and with each passing moment, my hands and feet became more blockish and icy. Surely this was what was meant by mortification of the flesh. I grimaced at the Reverend Shaw, who said there was no contradiction to be found in the biblical entreaty to render unto Caesar. I could have cared less what Caesar was or was not owed, because the winter sun through the window burned a nick upon the back of my neck.

My neck was on fire and my feet were numb with cold. They would find me dead in my place after service, with a scalded neck and blue, frostbitten feet. I slumped in the pew, away from the light, and poked the leather cover of my psalmbook with a gloved finger. That winter, I was twenty-two and discomfited at having been forced to attend service. Mama rapped me sharply with her Bible. I gasped and bent over, complaining of a fainting spell. The odor of wood oil filled my nostrils. I peered around Ma and caught the gaze of a brigadier general grinning from the pew directly across the aisle. He leaned over his knees with his hands upon his white breeches, mocking my discomfort.

I stared at the General in a way that I hoped made him feel much reduced in rank. I quirked a brow, which he mistook for encouragement, because he tickled the air with his fingers. I lifted my chin to let him know I disapproved, but he seemed pleased by my lofty pretense. He looked pointedly at the door and then at me. Forty, I estimated, about the same age as my pa, and he died of the afflictions of age in the spring of last year. This General was dark haired; he had a proud and stern countenance and remarkable blue eyes.

I was intrigued by his bad behavior and felt an odd prickling on the surface of my forearms when he regarded me as if determining my worth. My seventeen-year-old sister, the precocious Eloise, a child prone to homely outbursts about the mischief in her heart, squirmed about as the General smiled at her. At the tap of Eloise's fingers upon my skirt, I tipped my ear to catch her whispers.

"He is as proud as a prince and he's staring so lasciviously. What kind of a man stares so in church?"

I wiggled my fingers and blew upon them. "Glance away, Eloise, do not meet his gaze; you should elevate your thoughts and disregard that gentleman. And you hush up. Mama's going to beat me like a stray dog if I let you whisper at me through service."

"Mary, I was wrong. That is no stare; that rises to a leer. He is at least as old as Papa, and military men are poor, even the generals."

"Eloise, look at my neck. Am I getting a blister on my neck from sunburn?"

She wrinkled her nose and examined me. "No, but you have farmer wrinkles there. Looks to me as if you've passed summers tethered to the hemp-break wheels at Oxmoor. Mary!Willyou focus on the matter at hand? I was talking to you about that general over there who wants you. Listen to me!" Eloise rubbed her hands over mine. "I was at General Cadwallader's last evening for the musicale, and by the bye, Lizzie Griffin played the harp so ploddingly you would have thought her loaded up to her ears with laudanum. All Lizzie could talk about last night was your admirer, that ruddy-faced general across the aisle. She said he's come from St. Louis, and though he spends his days at the Western Department headquarters, he spends his nights searching for a bride. The General has declared himself ready for sons. Now he goes in search of their mother. The rumor is, several belles have set their caps for him."

"I hope he finds a respectable old widow. They could spoon castor oil into one another and commiserate about the gout."

"Lizzie says you're in view of his sparking." I ignored that comment. It was too dreadful to contemplate. Eloise blathered on: "It was Uncle William Clark who is guilty of arranging this. He thinks you're hopeless, Mary. He told me so, over supper yesterday. Just you watch, that general will force an introduction to Ma after service. Indeed, I'll wager Mama expects such a thing. Surely Uncle William has talked to her. It's a conspiracy to deprive you of your freedom. They're going to toss the yoke of subjugation about your shoulders and force you to give birth to furry little babies that look just like that general."

Mama swooped over me in a rustle of organdy, sending her anise-scented breath my way. She put her lips to my ear and whispered, "Mary, take one peek over the aisle at the handsome general and smile fetchingly."

I puckered my chin and rubbed my cold fingers upon it, because it pleasantly resembled a peach pit. "Fetchingly, Mama? What's your idea of 'fetchingly'?"

"Like this," Eloise simpered, rattling her eyelashes and rounding her lips into a coo.

I squinted at the General. By this time, he was brashly ignoring the sermon altogether and had turned sideways on the bench to stare boldly at me with an amused expression. The General had a disconcerting manner of looking at a woman. In the dark confines of my black satin slippers, I curled my toes.

Eloise leaned back and looked around behind my head. "It's not as though the General's hands are bluish and shaky. He's not drooling, and I don't see a walking stick. He appears vigorous. Maybe you could get one baby out of him before he dies."

Mama lifted the flat of her hand and walloped me.

"Mama, I did not come to church to harvest bruises!"

"I told you to smileonceat that general, Mary, not babble to Eloise all through service. Now, you girls be reverent, mind your prayers and your manners. And don't look at that general anymore. One glance is enough, or you'll appear too eager. Honestly, sometimes I feel I've failed utterly. I'm raising up a litter of Hottentots."

Of course, lingering in the air at all times was Mama's disappointment in me. Mama was a Gwathmey, one of theGrand English Gwathmeysof the Virginia tidewater. She was all sangfroid, stepping elegantly through her days as if expecting courtiers to assemble and pay homage. I suppose I am more like my father.

Pa's family, the Louisville Bullitts, were originally the French Huguenot Bouilits, a name that meant to seethe or boil, a fairly apt description of my temperament. He raged through his years, accumulating land, cash and human beings, then died of an apoplectic fit with his face swimming in a bowl of two o'clock burgoo. When I was seventeen, Pa spent a summer's income upon my coming-out ball. He had a garden of white flowers shipped from Louisiana, hired an orchestra and imported a gown of Flemish lace from Antwerp, then hosted a grand dinner for two hundred people.

"Why not just tether me and expose my bosom like a mulatto slave on the auction block?" I railed as I was pulled from my room. "Why not strip me down to my stays and let the boys see the goods?"

"Some might not like the look of your ass, and then where would you be?" Pa snorted as he arm-yanked me down the staircase.

The year I met the General, I had just celebrated my birthday and was averynaïve twenty-two-year-old, gone socially stale by Louisville's courtship standards. You see, I was widely perceived as being difficult. Mama had told me to select a man in my youth when I was freshest and allow him to guide me as nature had directed.

"You are a ripe and fruitful olive, Mary. You must learn to accept your vocation."

I waited for Mama to tell me what my vocation must be, but the wretched truth was that my belly was my future, and what future is that? She told me that my highest aspiration must be to bear children. To ensure my obedience, my parents sent me away to the Ursuline Convent in New Orleans on my fifteenth birthday. How I loathed the scorch of that city. Why, I felt as if I had been espaliered like a peach tree, forced to bloom in a climate where I could never flourish unless restrained. The Ursulines made an expert button polisher of me. I was forever getting into trouble for refusing to do as I was told. My punishment was to launder the chemises and polish the buttons of the whole convent with Spanish whiting until my fingers cracked and bled. In my third year, when I was eighteen, I was sent home midterm with a letter pinned to my frock-apron.

Dear Monsieur Bullitt,

Mary inspires the other girls to heresy and temporal revelry. We would rather she inflicted her obstinacy elsewhere.

Sincerely, Mother Froissart.

P.S. A generous donationwill notwork this time.

Mama had sobbed distressingly for a fortnight.

"If even the Romanists can't tame our girl, no one will; she is lost, O Lord, she is lost forever to the Kingdom. Maybe we could try giving her to the Baptists. I understand they are much less convivial than we Episcopalians."

Pa's jowls flapped as he paced the floor. "Pah! She's rotted clean through. Jaysus would get back up on his cross if he were married to her, so you may as well begin your search now for some sucker who is more patient than the Almighty."

Apparently, the patient sucker charged with my redemption was sitting across the aisle from me in the blue uniform of the United States Army. When the service ended, I rose stiffly from the pew and found my dress clinging immodestly to my legs. As I fluffed my petticoats, I peered up to see the General reveling in my discomfort. His eyes were full of wicked sparkle that I did not appreciate one little bit. And after service, my family shivered together upon the limestone steps while we waited for our carriage to be brought around. I huddled with Eloise, bouncing from one foot to another and hissing at our driver,"Hurry, hurry."Mama conversed with the reverend. While the children giggled and tumbled like marbles in the snow, Eloise pointed frantically at the vestry, warning me that the General was coming in our direction.

The Reverend Shaw gently steered Mama around to greet the General.

"Mrs. Bullitt, may I present General Henry Atkinson, recently arrived from St. Louis, and working temporarily at the Western Department headquarters here in Louisville."

"Oh, yes. I understand you are a good friend of Uncle William's?"

"Yes, we consult one another several times a week as he manages Indian affairs for Missouri, and I am required to keep the peace along the frontier."

"That's rather a large job, I'd imagine," Ma said as she hooked a strand of hair into the ruched lining of her bonnet.

"Aye, but requiring more patience than anything else."

"General, you must come to visit. On the morrow, perhaps?" Ma smiled pointedly at me.

As Ma and the reverend talked, the General lit his pipe and stared a proprietary stare at me. And though I hated to admit it, I found him handsome. His white trousers were tucked into his shiny black boots. Despite the cold, he wore no cape, and he unbuttoned his blue uniform coat and summed me up. I let my eyes wander and found myself looking at his hands. He had removed his gloves, and I stared at his broad palms and the fine, dark hair on his long fingers. What was it Lizzie Griffin said about a man's fingers? My eyes drifted to the General's white breeches.

Mama coughed, then pinched me on the upper arm.

The General narrowed his gaze with a small, secretive grin at me. Fearing he could read my mind, I quickly averted my glance to the snow under my slippers.

"Tomorrow, then, Miss Bullitt?" the General asked.

I shrugged my response, and he smiled once again.

Ma bowed her head as if the Holy Ghost had anointed her. The drivers pulled the two barouches to the curb, and all thirteen of us shuffled in, sat atop one another, poking and knobbing until we were situated to bear the short ride home. I tried to calm the shrews running wild through my belly as I took a last look at the General.

"He is a bit insouciant, but this is to be expected." Ma gave me a blithe pat upon the hand, then pulled the shade.

On the morning the General came to call, he tied his horse to the iron hitching post by the stone steps. The General strolled through the house with his hands clasped firmly behind his back, looking directly ahead as if the walls were invisible and he was keeping watch over something on a distant horizon. He made no comment on the furnishings or frippery. I admired this about him; it raised him in my estimation.

The General found the great hall crowded with my little brothers and sisters, who thundered up the stairs, slid down the balustrade, then started over again, hollering all the while. They glared at him as if he were something vile that had slithered up from the falls. He glared back, and they were duly cowed. Mama danced down the stairs with a regal swishing noise, one hand lifting the skirts of her aubergine gown, the other waving a welcome to the General. But her greeting was interrupted by footfalls upon the threshold of the front entrance, followed by Uncle William Clark's voice sounding sharply and urgently.

Eloise clutched at me with a worried look. "What do you suppose they're about?"

"Miss Eloise, we must investigate," I whispered.

It was easy to dash about undetected in our house. Pa had built the limestone thing as a monument to himself. I called it "the old sepulcher," which infuriated Mama. Visitors wandered through the rooms, gaping at the black walnut floors so polished they appeared as dark water underfoot, at the lofty ceilings, the tiger-maple and rosewood marquetry, the sixteenth-century Italian furniture, Flemish tapestries and hand-painted wallpapers. There were portraits of dead Bullitts, Gwathmeys and Clarks in every hall.

But Eloise and I were still in dressing robes with our hair floating behind us. To be seen in sleeping clothes and naked feet by men, worse yet, by a man who had come to court, was an act of unpardonable lewdness, punishable by a whipping. Thrilled by the promise of intrigue and our own brashness, we crept hand in hand toward the library, listening to the General and Uncle William Clark bark at one another. Having had his hopes for the governorship of Missouri dashed, Uncle served as the Superintendent of Indian Affairs, and the General enforced federal regulations pertaining to the Indians on the frontier. That was all I understood of their lives. Mama said Uncle and the General were fast friends.

Eloise squared her shoulders against the wall as if someone were pressing a musket to her heart. She lifted her chin and stared at the ceiling. I thought her posture rather too dramatic. I crouched low, hugging my knees as I strained to hear what they were saying.

Uncle was agitated. He paced back and forth, popping his fist into his palm to emphasize his points: "I shall thrust a wedge into the heart of that tribe, that's what. Split 'em in two. I will make it clear to the Sauk Nation that I will not negotiate with that scrawny little bastard Black Hawk."

I peeked round the pilaster to see Uncle making throttling motions with his hands.

The General lit his pipe and spoke calmly. "Who will you negotiate with? Certainly, Keokuk can not be trusted. I will not put my faith in a man who steals annuities from his own people, keeps a harem and dresses like a dandy."

Fishing his snuff box from his pocket, Uncle William Clark said, "I'll pay him enough that he can be trusted. And incidentally, old friend, half of all of my troubles I attribute to you. What the hell did you do to Black Hawk to make him want to kill you and every white soul on the frontier? He hates both your innards and your out-ards."

The General clenched the silver stem of his pipe between his teeth and tented his fingers. "That's a small matter, greatly exaggerated."

"Don't scoop that fuggin' balderdash at me, Henry. Speak the truth, damn you."

When the General maintained his silence, flicking an ash away from his sleeve, Uncle William raged, "I have a right to know, don't I? What the fug did you do to him? Sleep with his wife? Gig the family dog? Or did you gig his wife and sleep with his dog?"

The General smirked. Uncle pointed a warning finger at him. "Tell me, you sonofabitch."

"Well, if you're going to get into a dudgeon about it. It began in the winter of 1814, on the shores of Lake Champlain, when I was a young captain leading a company of men through the woods in a snowfall. We knew the British lines were somewhere to the north of us, and we feared stumbling into them. As twilight descended, we were too far from the barracks and had to make camp, but we could not build fires for fear of alerting the British to our position. My men glanced fearfully about at each snap of twig and birdcall. We could always see the British coming because of their garish costume. We could hear them coming because they announced themselves with bagpipes. It was the Sauk we feared. They were invisible warriors in the woods. And the light was so gray...well...I had picked where we were going to bivouac, and the men had begun to settle when the air was cut by eerie war whoops. My men slipped their bayonets onto their muskets, poured powder and balls and affixed their flints with clumsy fingers. And we waited. The outlines of the trees were blurred by the snow, and the growing darkness, yet we sensed movement toward us. My men held their fire until the first of the Sauk were clearly visible, creeping through the underbrush. We fired; the woods lit up with powder blast. Because of the smoke, I could not see anything. The Sauk came out of the darkness, running with their axes held high.

"A slight-made young warrior, bald except for his vermilion roach, came at me with his knife in one hand, an axe in the other. He was no more than seventeen. He cut the outside of my thigh, and we struggled in the snow and the muck. I was much taller and heavier than he, but when I rolled atop him, he tried to drub me with his axe. I cut him. With his own knife. I cut the vein on the side of his throat.

"All around me, I heard men go down, bludgeoned, stabbed...when the Sauk took scalps, it sounded like the rending of fabric. In the distance, I could hear the British setting up their artillery. They must have intended to blow the forest into slivers with their six-pound guns, because this was a dense wood and they were long yards away from us. There was a moment when I paused and squinted through the snow and darkness, looking about for ways to help my men. I heard a cry of anguish. A Sauk warrior leapt before me. Despite the cold, he wore only a breechclout and moccasins, his thin and narrow body bore not a bit of fat. He crouched, staring at the dead boy behind me.

"The gash on my leg flowed blood like a creek after the spring thaw, and I felt weak. I held my pistol before me, but my hands were clumsy from the cold and they slipped all over the butt. I couldn't get a grip on it. I dropped it behind me and yanked my saber from its scabbard. We circled for a few minutes, then the Sauk leapt upon me the way a cougar jumps an elk on a game trail. I couldn't believe his speed. He was going to kill me very quickly. With every bit of strength I could muster, I got to my feet, but he was right on me again. He had the advantage over me.

"But then something happened that saved my life; I am convinced of it. The British opened fire with their big guns. The concussive blast was so great that the Sauk warrior was thrown off of me, and in the smoke and confusion, I saw my men running. I looked up and there had to have been a whole regiment of British coming across the creek. I took advantage of the smoke cover, grabbed my pistol out of the snow and joined my men. I glanced back at the Sauk warrior, and he was crouched over the dead boy, howling out his pain and despair. I tell you, that was bad to see. But the second time I looked back, the Sauk was staring at me, and seeing me look at him, he raised his hand and made a slicing motion across his throat, then across his own scalp to let me know what he thought of me."

"That was Black Hawk?" Uncle William asked, pouring himself a dram of bourbon.

"That was Black Hawk." The General studied the ceiling of the library as if it were a map to the promised land. Uncle pinched, then snorted the snuff from an onyx vial. From my vantage point, his snuff box looked like a black plum in his hand. He said, "Black Hawk is a pompous little scaramouche with aspirations to be the next Tecumseh. But he is too fuggin' shortsighted ever to unite the Lake Nations."

"Agh, Clark, but if he ever does...if Black Hawk ever unites the Lake tribes...my men will be outnumbered six to one. Say good-bye to every white soul on the frontier. And I don't think he's stupid or shortsighted."

"General, you seem awfully generously disposed toward the little savage, given he wants to slit you nose to nuts. What is it that grips you? Guilt?"

The General's boots pressed dents into the leather of the ottoman.

Uncle ran his hands through his long gray hair with its few coppery strands and blurted, "I don't care a shat about that little momma-sucker. I'll starve him out. Starve him!" The General squinted up at Uncle through a blue cloud of pipe smoke.

"MARY BULLITT! You areen déshabillé!"

I flinched, squeezed my eyes shut and then rose up to accept my punishment. It was Mama. Her pretty face was mottled red with fury as she yanked me and Eloise by our collars and shook us hard. Uncle and the General stepped into the hallway, but I had been struck all of a heap by the General's bloody story of Black Hawk. I mulled over the idea of Black Hawk's vengeance, told in half measures, while everyone chattered around me. If I had the wisdom of a few more years, I would have known that the General had omitted whole chapters from his account. But at the time, I goggled at him, as stunned as a duck in a thunderstorm.

The General shook his head as if we had offended his delicate sensibilities. "Sir," I began, meeting his eye because I wanted to quiz him, but Uncle William interrupted, teasing me as if I were a child. It was his custom, after all.

"You, Miss Mary, do I see your feet?"

I tucked my bare feet under my robe as best as I was able. "Uncle, I can see your feet too."

"Yes, Miss Mary, but I'm wearing shoes."

"Yes, Uncle, but they're ugly shoes."

The General knit his brow and looked at my mama, who dipped a little, apologizing, "General, ordinarily Mary is the embodiment of piety, purity, submissiveness and -- "

Uncle William clapped a hand over his mouth, laughing at Mama's bald lie. Eloise hawed like an old mule suffering the lung rot, and Mama triggered a wallop upside the back of her head that left her tingly for weeks.

I called out over the banister as Mama dragged me up the stairs, "After all these years passing, Black Hawk doesn't remember who you are, does he, General?" When I peeked back over my shoulder, a smile played over the General's lips, and right there, before everyone, before Mama and Uncle William,he winked at me!

Eloise gasped at his audacity, "Mama, that general winked at Mary!"

"Dahlia, put Mary in her rose gown of India mull, it makes her appear demure. No woman, even Mary, can look rebellious in pink."

"He winked at me, Mama. I think he's dissipated. Miss Mary Wollstonecraft says only corrupt men wink."

Dahlia tied my waist tapers, as Mama violently jerked my hair up atop my head, and with her teeth clenched, growled at me, "Do not mentionthat woman'sname in my house. She is immoral and she is dangerous." Mama continued her hopeful preparations. She turned me in rough circles, lifted my top lip with her small finger and rubbed at the space between my teeth with her fingernail, muttering, "At least your front teeth are still fine and white." She gripped my wrist and pointed a warning finger at Eloise. "You stay right there, young lady, don't you interfere. Mary, repeat after me -- piety, purity, submissiveness and domesticity."

"Piety..." I sighed, as Mama hauled me down the staircase, depositing me before the library entrance. I drifted sullenly through the door and glanced around for Uncle William, but apparently he had left us. The General bowed, then pressed the knuckles of my hand to his lipsand held it there.I rolled my eyes at the ceiling and let him nibble at me as long as it pleased him.

"Tasty, isn't it, General?" I said.

He laughed and gave my arm a playful jiggle before releasing it. "Tasty like a stewed ham hock, Miss Bullitt."

"Not a very auspicious beginning, sir -- likening me to a pig, that is."

"Mary Bullitt!" Mama exclaimed, shoving me down onto a chaise. The General postured upon Pa's favorite chair as the high-yellow kitchen maid brought a tray of tea and gâteaux. I wondered which of the General's legs had been cut by the Sauk warrior's knife while Mama engaged him in breathless conversation. He watched her red silk handkerchief flutter against her breast. She confessed her relief at having a Southern gentleman in her parlor as opposed to that vicious freshet of Yankees who'd crowded the house of late.

"It is one thing to have Yankee officers coming to court, it is quite another to consider that your grandchild might be one of them," Ma said.

"Yes, yes indeed, Mrs. Bullitt." The General glanced pointedly at my hips as if to assess my breeding capability.

I cringed. The man just arrived and Mama had him filling my belly with children. The window admitted a wan breeze and I turned to welcome it. Dahlia, my waiting maid, sat upon the rug before the door. The General and I shared a skeptical look as Dahlia touched her fingers to her head scarf and loosed a small cough to let Mama know she had arrived.

"Oh, General," Mama said, "that is Dahlia. She will matron the two of you, for today is my receiving day, and I must take calls from the ladies of Louisville. You will, I hope, understand?"

The General bid her good day. Mama banged the latch into the jamb with the finality of the undertaker pulling shut the doors of a family mausoleum. Dahlia cast a sleepy glance at us, waved a little wave, yawned, then slumped over in a deep sleep on the rug.

We scrutinized one another for as long as it pleased us. The General had a fan of lines at the corners of his blue eyes and a sprinkle of gray in his hair. I thought he was a stark representation of prime on the cusp of decay. I could hear all of Louisville gossiping now:Have you heard about Mary Ann Bullitt and her dignified old General?Ugh. I made fists and pressed my knuckles into the chaise's brocade until a red imprint bloomed on my skin.

It was time someone said something.

"Are you enjoying your visit to Louisville, General?"

"Yes. Are you looking forward to the spring cotillion season, Miss Bullitt?"

"No. I despise cotillions."

"I understand entirely."

"How nice to be understood."

He rubbed a hand over his face to steady his expression. "I must go now," he said, rising with great dignity from his chair as if he expected me to salute him. His dismay was obvious when I jumped up gleefully, with a clap of my hands.

"General, may I give you directions to Lizzie Griffin's house? I've heard she finds you quite interesting."

"I do not reciprocate that sentiment, Miss Bullitt."

"That's unfortunate for me, isn't it?" I muttered, putting a hand to the globe and giving it a spin. The General paused a moment, then looked at the ceiling as if contemplating his next action.

I said hopefully, "Now that we're alone, you should know I'm rotted clean through. You can leave and I'll tell Mama I was horrible to you and she'll believe me. You've lingered longer than most of my suitors."

"Sit down, Miss Bullitt, right here."

He pointed at the ottoman and waited for me to obey him.

"Why? Because that's a lower position than you have? So I can gaze up admiringly at you? No, General, I think I'll sit on the table. Then I'll be higher up than you."

"Suit yourself, young lady."

"And so I shall." I tossed the books off the drum table beside his chair, planted myself and held the globe as if it were an infant.

"Miss Bullitt, I want you to share with me your opinion of the world and how you see your place in it."

I blinked at him. No grown man had ever asked me such a question before. It gave me reason to consider that the General might not be so decrepit after all. He waited patiently for my response, cupping his chin in one hand, focusing on my face an unblinking gaze that wandered now and again from my throat to my knees. Oh, he was brash. I paused dramatically, looked about for something clever to say, and finding nothing inspirational in the cavernous emptiness of my head, said, "I think the world in general and Louisville in particular is being ruined by civilization. Why, they're paving the streets of this city with cobbles -- "

"No!"He interrupted with mock incredulity and slapped a hand to his jaw.

I began to recount the depredations of encroaching civilization for him. "I hear tell there's an ordinance being bandied to stop the boys from fighting before the grog houses; what, I ask you, will they do to occupy their time now? There are too many churches being built in Louisville and too many ministers moving in to fill the pulpits. There are rules everywhere governing everyone, as if we wanted rules at all. The city and all of the Kentucky people in it are going to be ruined by gentility, and I'll be destroyed right along with them."

The General circled around behind me where I sat and leaned over me. His hand closed over mine and he lifted my forefinger, then laid it on the globe over the township of St. Louis. A darkling sensation went all through me. I had never before experienced such an intimate connection with the body of a grown man. I could feel the rough wool of his coat against my bare arms as he pressed against me, and when he leaned forward so that I could feel his breath upon my neck, I nearly went limp against him. Though convention told me to be outraged by his breach of decorum, I was paralyzed with enjoyment. Indeed, I rehearsed womanly outrage in my mind, but I didn't feel it and feared a display would ring false.

He returned to his chair.

"Miss Bullitt, you ever been to the Indian country?"

"No, sir."

"Why not?"

"Why would I go to the Indian country? Who's there besides Black Hawk? And you'd better kill him before he kills you. To my way of thinking, you've got to turn the Old Testament upside down. None of this eye for an eye business. You've got to steal away the other fellow's eyes before he takes yours. What do you think of that?"

He took my hand once again, I felt the corners of my mouth lifting in a traitorous smile. His breath smelled like almonds. "Black Hawk poses no danger; he's an old man. He must be nearing fifty winters now."

I narrowed my eyes and yanked free of him.

"You've got to be nearing fifty winters too, so you're not a danger to me."

The General cast a sly look at me, then put his hands on the toes of my slippers. I could feel the heat of his hands through the silk, and I leaned over him. The color rose on his cheeks when I came very close and whispered, "You're not telling the truth about that Indian who wants to kill you. I can sniff out fibbing, and you're fibbing to me now, General. You often fib to women, don't you?"

"I only fib to the wicked ones." His eyes twinkled at me.

I nudged at his shoulder, ruffling the fringe of his epaulet, and said, "Tell me about the frontier. What does St. Louis look like? I hear they call it Little Rome because it's crowded with the popish French. Is that true?"

As he was unduly proud of himself, I expected the hearty budget of bragging tales customary to military men. But when the General began to talk in his North Carolina drawl of what it meant to live in a place where there were no cities, in a place beyond the telling of rules, where the most reckless desires of men were manifest, I closed my eyes and allowed him to lull me across time and space to places I had never seen. He talked and talked for nearly two hours, but he said nothing more of Black Hawk.

When I asked him once again about Black Hawk, he demurred, "Not yet, Miss Bullitt. You are far too accustomed to receiving whatever you wish."

"General, you are far too accustomed to giving out what no one wants."

The General smiled at me and rose from the chair. With a quick motion, he gripped my wrist, then brought my fingertips to his lips. I resisted the urge to rub them back and forth to feel the texture of his mouth.

"Then it's decided. You'll do fine," he said, his look sweeping me from head to toe.

"I'll what?"

"Mind what I say."

A derisive glottal noise erupted out of me, and he dropped my hand as if I had the scrofula.

"What was that noise that just came out of you, Miss Bullitt?"

"A stomach disturbance."

He regarded me doubtfully, then stepped around Dahlia, who still slept on the floor. I trotted along after him like an amiable puppy.

"Now, Mary, I must go play brag with General Gaines," he said, turning to face me. "Shall I see you tomorrow, then?" He winked and touched his fingertips to his brow in a sort of casual salute.

Before I could give my answer, Mama scrambled down the steps and, with a conciliatory smile to the General, yanked me by the pelerine, back into the house, all the while scolding me for running out-of-doors after a suitor as if I were some overeager hill cracker in heat.

On the second day the General laid siege to our household, a steady rain warped the wood floors until opening doors traced perfect arcs through the beeswax finish. I lay abed and watched a dreary light filter through the window as a servant brought my breakfast of biscuits and milk. By eight, I'd been corseted, at half past I accompanied Ma to the storeroom. Ma did not release the keys to her stores to anyone as our family's livelihood depended upon her careful management of the preserves, dry goods and medicines.

"Mama? About this General...I think you should know, he vexes me terribly."

Ma reviewed her list and squinted at the low state of copper polish, then muttered something about all of us being about to die from verdigris poisoning.

"What don't you like about him, Mary?"

Ma removed a barlow knife from her pocket, peeled away the brown wrapper from the nine-pound loaf of sugar and took a chunk out of the white brick for Dahlia.

"He's too old."

"The General is the perfect age for marrying. You aren't suited to marry a boy. What else?"

"He has a rotten temperament, Mama. He's obdurate. He bosses me around."

When Ma finally began to speak, her voice sounded, as always, like a low hymn with distinct rhythms. "Mary, I observed the two of you together for a few moments. It struck me that between your mulishness and his pride flourishes paradise."

"Paradise?"

Mama sighed. "Yes, well to the devil, an inferno is paradise. See here, Mary, the two of you relish this sparking and circling. After you marry, and this man will offer marriage, you'll take turns dethroning one another. He'll lord it over you for a time until you tire of it, then you'll usurp him in a brief but thrilling revolution until he hobbles you once again. And so on. When the General talks to you, does his conversation interest you?"

"He told me an Indian wants to kill him."

Mama ignored this. "Is the General kind?"

"No, I fear he is the sort who will apply stripes to me before bedtime."

Mama scrutinized her candle inventory.

"Now you're being silly. I happen to know he is a gentleman of the highest order, stern perhaps, accustomed to deference from all living things, but still and all, truly gentle in his manner and desirous of pleasing you. No, I can guess a man's proclivities at the outset and this one is kindhearted. And for some reason, he is the only man come a-courting who doesn't think you're a harpy. Dahlia and Hannah, you may go."

Mama waited until they were down the stairs before she spoke.

"Let us have an understanding between us, Mary, and I say this with all solemnity -- I would never force you into marriage."

"You wouldn't?"

"No, I wouldn't. And if I truly believed you'd be happy to live out your days in this house as a maiden lady, then I would tell you so now. I would love your company forever. But, Mary, I am asking you to consider, for the first time in your life, that you have a very difficult nature. You would be miserable if you were married to some bird-hearted crumpet of a boy. The General is a good match for you; he could show you so much of the world, and in a way you'd like to see it."

"Why can't I see the world by myself, Ma? Why do I need him?"

"You don'tneedhim. But neither are you suited to...to a life of celibacy, Mary."

"Oh my God, I can't believe you just said that."

"Donotblaspheme in my presence! Part of your dislike of the General is prompted by the stew of emotions he boils up in you. There is a very heady current between the two of you when you are together; I sense it and you need to recognize that he understands it. You're misinterpreting what your heart tells you. He's the first man you've met who won't grovel for you. Virtue in a woman is a good thing except when it's...well,antique,my dear. Then it changes into something, ah, something much less appealing. For once in your life, think about your actions before you turn him away for good. You consider my words before he comes to call today and try to behave. The last thing you want is to regret sending away the one man who could make you happy."

I took my leave of Ma to greet Mister Rammey, who had come to give me lessons in Italian song. At ten I played the harp for an hour, all the while considering Ma's words. I dined on turkey galantine at two with my lady cousins, Louisiana, Octavia and Celeste, but the memory of my last encounter with the General scratched around in my head like a caged squirrel. At three, I reviewed the calling cards we'd received that day, taking them from the gold-plated receiver, a shallow bowl uplifted by a full-breasted goddess who appeared blissful in her duties as she stood on her pediment. For a long while, I sat miserably on the staircase, stared up at the clerestory windows above the doors and grumped about my future. What if nothing ever changed for me? My days were something like living inside a field glass, it seemed each was a view to the last, one telescoping upon the other, the same narrow view recurring over and again with maddening clarity.

That night, a bath was drawn for me in my bedroom. I immersed myself into the tepid water and examined the red marks left on my breasts and ribs by the whale-bone corset stays. As I bathed, I traced each angry indentation with a wet finger, hoping to translate the secret cursive of the lines, the code of duty and obligation written into my skin by the Louisville society that had governed me since birth. Maybe Mama was just plain wrong about me. Maybe I was meant to make a life for myself. I would read all of the books I'd hesitated starting, I would ride out and explore reaches of Kentucky I had not seen. A lifetime of self-indulgent spinsterly pursuits awaited me -- such was the future I yearned for, wasn't it? The fulsome and independent life of an aged maiden lady. Mary Ann Bullitt: spinster. I liked the sound of it. And it made me perfectly miserable because I wanted my journey. I wanted to see the gold and russet prairies of autumn, and I wanted to cross the same mountains Uncle William Clark and his Corps of Discovery had crossed in the winters after I was born.

When I was young, Uncle William would tell me how he had planned the arrival of the Corps of Discovery at the Pacific Ocean to coincide with my birthday. For the men of the corps arrived on the western shore in December of 1805, and my uncle was so joyous, that he carved his name and mine into an alder tree overlooking the great waters. He would say to me, "Mary, on that day, despite my jubilance at what we had discovered, I was troubled by the idea that you and everyone I loved back home were celebrating your second birthday. I could not bring you a gift, so I carved your name into a tree in the wilderness."

And then Uncle William would sigh and say, "I apologize, Niece."

And knowing how the story ended, I would pretend concern and touch my hands to his cheeks and plead, "Why do you apologize, Uncle?"

"Without your knowledge or permission, Mary, I gave you then, to the West. You were married to the West when you were only two years old."

I stepped from the tub and pulled the pins from my hair. I watched the dark length of it fall to the white curve of my calves, then stared at myself in the mirror. With arms outstretched, I turned barefoot circles upon the old Turkish carpet until my hair lifted and splayed like wings searching for loft over the windy savanna and the spreading dark rivers of the West.

Copyright © 2001 by Micaela Gilchrist

Excerpted from The Good Journey: A Novel by Micaela Gilchrist

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.