Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

| Maps | p. xi |

| Prologue | p. 3 |

| Two Failed Men with Great Potential | p. 7 |

| Grant Awakens | p. 38 |

| Sherman Goes In | p. 50 |

| Grant Moves Forward, with Sherman in a Supporting Role | p. 80 |

| The Bond Forged at Shiloh | p. 90 |

| Political Problems, Military Challenges: The Vicksburg Campaign Develops | p. 130 |

| The Siege of Vicksburg | p. 160 |

| Pain and Pleasure on the Long Road to Chattanooga and Missionary Ridge | p. 190 |

| Confusion at Chattanooga | p. 209 |

| Grant and Sherman Begin to Develop the Winning Strategy | p. 232 |

| Sherman Saves Lincoln's Presidential Campaign | p. 248 |

| Professional Judgment and Personal Friendship: Savannah for Christmas | p. 263 |

| The March Through the Carolinas, and an Additional Test of Friendship | p. 283 |

| Grant, Sherman, and Abraham Lincoln Hold a Council of War-and Peace | p. 294 |

| "I now feel like ending the matter": Grant's Final Offensive | p. 305 |

| The Days After Appomattox: Joy and Grief | p. 314 |

| Sherman in Trouble | p. 337 |

| Grant, Sherman, and the Radicals | p. 358 |

| A Parade for Everyone, and a Hearing for Sherman | p. 367 |

| The Past and Future March Up Pennsylvania Avenue | p. 379 |

| L'Envoi | p. 400 |

| Notes | p. 403 |

| Bibliography | p. 429 |

| Acknowledgments | p. 437 |

| Index | p. 445 |

| Table of Contents provided by Ingram. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

Two Failed Men With Great Potential

In December of 1860, five months before the Civil War began, two men who had resigned from the United States Army earlier in their lives reviewed their respective situations.

From Galena, Illinois, a small city of fourteen thousand, four miles east of the Mississippi River and just south of the Wisconsin border, the first of these men, former captain Ulysses S. Grant, wrote a friend, "In my new employment I have become pretty conversant . . . I hope to be made a partner soon, and am sanguine that a competency at least can be made out of the business."

A man who had graduated seventeen years before from the United States Military Academy at West Point, something that in itself conferred a certain prestige and social status, Grant was now a clerk in his stern father's small company, which operated a tannery as well as leather goods stores in several towns. Just six years previous, after four years as a cadet and eleven as an officer, including brave and efficient service during the Mexican War, his military career had come to a bad end. Stationed at remote posts in California without his wife and two children, Grant became bored and lonely. During the long separation from his wife, Julia, a highly intelligent, lively, affectionate woman who adored him as he adored her, he began to drink. In 1854, when Grant was thirty-two, his regimental commander forced him to resign from the army for being drunk while handing out money to troops on a payday.

Returning to Missouri, Grant struggled for four years to support his little family by farming land near St. Louis that belonged to his wife and father-in-law. Despite working hard, avoiding alcohol, and remaining optimistic—at one point he wrote to his father, who then lived in Kentucky, "Every day I like farming better and I do not doubt money is to be made at it"—events worked against him. A combination of weather-ruined crops and falling commodity prices left him with with one slim chance to get by. Hiring two slaves from their owners, and borrowing from his father-in-law a slave whom he later bought and set free, Grant and his new field hands began cutting down trees on the farm, sawing them into logs, and taking them to St. Louis to sell as firewood. Sometimes Grant brought his logs to houses whose owners arranged for deliveries, and on other days he peddled them on the street.

Wearing his faded old blue army overcoat, from which he had removed the insignia, he sometimes encountered officers who knew him from the past. Brigadier General William S. Harney, "resplendent in a new uniform" as he passed through St. Louis to campaign against the Sioux, saw Grant handling the reins of a team of horses pulling a wagon stacked with logs. Harney exclaimed, "Why, Grant, what in blazes are you doing here?" Grant answered, "Well, General, I'm hauling firewood." On another day, an old comrade looking for Grant's farm asked directions of a nondescript man driving a load into the city, only to realize that he was speaking to Grant. In response to his startled, "Great God, Grant, what are you doing?" he received the laconic reply, "I'm solving the problem of poverty."

On December 23, 1857, Ulysses S. Grant pawned his gold watch for twenty-two dollars to buy Christmas presents for Julia, who was seven months pregnant, and their three children. Nothing improved: bad weather destroyed most of the crops Grant planted in the spring of 1858, and a freak freeze on June 5 finished off the rest. During the summer, the Grants' ten-year-old son Fred nearly died of typhoid. In early September Grant wrote to his sister Mary that "Julia and I are both sick with chills and fever."

The end had come for Grant as a farmer. In the autumn of 1858, an auctioneer sold off his remaining animals, crops, and equipment. He, Julia, and their four children moved into St. Louis, where a cousin of Julia's had been persuaded to make him a partner in his real estate firm. Grant's job was to collect rents and sell houses, but even in a sharply rising real estate market, he could not make money. After nine months he was told that the partnership had been dissolved: he was unemployed. Next, after being turned down for the position of county engineer for lack of the right political connections, he found a job in the federal customshouse but was replaced after a month, again a victim of political patronage. Heavily in debt and behind in his rent, Grant could not support his family. A friend who saw him walking the streets looking for work described a man "shabbily dressed . . . his face anxious," sunk in "profound discouragement." Finally Grant turned in desperation to his austere father, who had earlier rejected his appeal for a substantial loan, and the elder Grant created a job for him as a clerk at the leather goods store in Galena. A man who ran a jewelry store across the street recalled this, from the time when Grant was describing himself as "pretty conversant" with his new job. "Grant was a very poor businessman, and never liked to wait on customers . . . [He] would go behind the counter, very reluctantly, and drag down whatever was wanted; but hardly ever knew the price of it, and, in nine cases out of ten, he charged either too much or too little."

That was Grant as he lived in Galena on the eve of the Civil War—an ordinary-looking man of thirty-eight, five feet eight inches tall and weighing 135 pounds, somewhat stooped and with a short brown beard, a quiet man who smoked a pipe and by then had some false teeth. He had never wanted a military career: he went to West Point only because his autocratic father, who had . . .

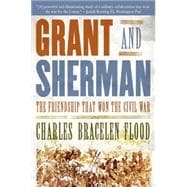

Grant and Sherman

Excerpted from Grant and Sherman: The Friendship That Won the Civil War by Charles Bracelen Flood, Charles B. Flood

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.