What is included with this book?

| Introduction | 1 | (8) | |||

|

|||||

|

9 | (20) | |||

|

|||||

|

29 | (22) | |||

|

|||||

|

51 | (24) | |||

|

|||||

|

75 | (30) | |||

|

|||||

|

105 | (26) | |||

|

|||||

|

131 | (42) | |||

|

|||||

|

173 | (34) | |||

|

|||||

|

207 | (30) | |||

|

|||||

|

237 | (30) | |||

|

|||||

|

267 | (22) | |||

|

|||||

|

289 | (26) | |||

|

|||||

|

315 | (34) | |||

| Epilogue | 349 | (20) | |||

| Notes | 369 | (20) | |||

| Bibliography | 389 | (10) | |||

| Acknowledgments | 399 | (6) | |||

| Index | 405 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Civil War Begins

"Money!" Abraham Lincoln exclaimed. "I don't know anything about 'money.'"

The President was typically modest, evasive and adept at feigning ignorance when he did not want to be pinned down. At a meeting with a delegation of New York bankers and financiers well into the Civil War, Lincoln fully understood that the United States needed money to save the Union. So did Lincoln's anxious Treasury Secretary, Salmon P. Chase. From the conflict's outset, the Union had had to fight while nearly broke. Chase's initial estimate after the taking of Fort Sumter was that the war would cost $320 million. After all, most experts figured at the time, the war could not last long -- "two or three months at the furthest," theChicago Tribunepredicted -- so the Treasury Department's first proposal was for three-quarters of the money to be borrowed from banks. Once the war was over, the money would be repaid quickly, Chase and others thought. But after the first months passed, the optimistic predictions unraveled, leaving the Treasury only $2 million on hand in the summer of 1861. While Union soldiers reeled from defeat after defeat, the banks balked at the administration's demands for loans, especially at the federal requirement that loans be paid in gold and silver.

Lincoln and Chase had a basis for thinking that the Union's credit was good and its eventual prospects even better. The North's strengths in fighting the war derived from a two-to-one advantage over the South in population, income and wealth. The Union side also had a 300 percent advantage in railroad miles, a powerful industrial foundation and vast holdings of unoccupied public land, including the gold-producing regions of the West. But these were assets not easily transformed into the cash to equip and send armies into battle. For months the banks warned Lincoln and Chase that reliance on borrowing when the future was uncertain was risky and potentially inflationary. One such warning was delivered to the Treasury Secretary when he traveled to New York for a private meeting in 1861 with the barons of capitalism at the New York Customs House near Wall Street, where financiers gathered from across the Northeast region. The Secretary was there to discuss the sale of new twenty-year bonds, but the low interest rate of 7 percent and the request that the bonds be purchased in gold unsettled the bankers in the room. They felt that the Treasury Department was looking on them as some sort of bottomless reserve, when the banks' solvency was actually very precarious.

Chase comprehended their situation at one level, but he also viewed the banks' reluctance to buy the bonds as arrogant and unpatriotic. The Treasury Secretary knew about the dangers of inflation, but he did have a war to fight, and he would do what was needed. He warned that, if necessary, he was prepared to print money to pay for the war, even if the price of a breakfast rose to $1,000. The banks were sympathetic, but they wanted to know about the prospects of repayment. At one point, James Gallatin of National Bank of New York, the son of Thomas Jefferson's Treasury Secretary, spoke up. What if more military reverses occurred? What if Britain or France intervened on the side of the Confederacy? What if the war went on not for months but for years? Another banker threatened to stop doing business with the federal government altogether unless Washington did something to shore up federal finances. His comment came across to the Treasury Secretary as a threat.

"No!" Chase fired back. "It is not the business of the secretary of the Treasury to receive an ultimatum, but to declare one if necessary."

By the end of 1861, Chase and Lincoln pried $150 million from the banks at 7.3 percent interest, but at great cost to the solvency of both the banks and the nation. As the men at the Customs House had feared, their reserves were so far gone that they had to suspend payments in gold and silver to their own customers. Soon afterward, the federal government followed suit, unable to honor its own payments with gold. These were brutal blows to Union credit. Without revenues, the federal government would not be able to turn to the banks again for more loans. More revenues meant only one thing: more taxes. That requirement would mean a new kind of tax, with far-reaching impact on the nation's finances.

Within the next six months, on July 1, 1862, Lincoln signed the first federal income tax in United States history. It was a momentous piece of legislation, rivaling, in its way, the abolition of slavery, the Homestead Act, the establishment of a national currency and federal bank regulation. Enactment of an income tax ushered in a new era of thinking about who should pay, who should sacrifice and who should gain from the federal government at a time of war. It established what until then was considered a revolutionary principle: the idea of taxing rich people at a higher rate compared to the rate for people less well off. Yet once established, that principle became a permanent feature of the American political and economic landscape.

The story of how the financial crisis of the Civil War led to a progressive income tax is a story not simply of war but also of the tumultuous economic and political change brought on by a new industrial age. The tax was essential to saving the Union and freeing the slaves. And although the tax was repealed shortly after the war ended, it left a monumental legacy by redefining the relationship between wealth and fairness. The Civil War income tax was a benchmark for how much America had been transformed in the first half of the nineteenth century. It established a foundation for the changes to come in the century's second half and for the years after that.

The tax that was enacted during the heat of a national crisis resulted from many decades of growth and change. Before the Civil War, the United States was populated primarily east of Kansas and on the Pacific coast. It was dominated by small business and farmers dependent on staples and manufactured goods from abroad. Americans kept their investments in their communities, and they used local currencies issued by their own banks. Thousands of different paper currencies, some issued by banks and some simply bogus, circulated as money among Americans. The national government was tiny, with little power to oversee this chaos. The government delivered the mail, collected tariffs and oversaw foreign affairs, but did little else. The Army when Lincoln took office had about 16,000 men, barely enough to protect Americans from Indians. Such was Washington's complacency that in June of 1860, the House Ways and Means Committee eliminated $1 million from a naval appropriations bill to repair and equip vessels. "I am tired of appropriating money for the army and navy when, absolutely, they are of no use whatsoever," said one member of Congress.

Complacency was perhaps understandable. No serious external threat cast a shadow on the prosperity achieved by America in the first half of the nineteenth century. After 1815, nothing seemed to stand in the way as Americans conquered, settled, annexed and purchased new territory, quadrupling the nation's size and population. Exports grew nearly two-and-a-half times in 50 years, to $243 million. In the South, King Cotton dominated world markets, supplying the mills of New England and Europe and enriching shippers, lenders and other middlemen based in New York. From 1817 to 1837, the output of the textile industry in New England rose from 4 million yards of cotton cloth to 308 million. The system of interchangeable parts revolutionized the production of machinery and arms, enabling the United States to surpass Britain in industrial might. Factories required workers. Waves of immigrants joined with Americans from the farm regions to pour into the great American metropolises seeking the means to improve their lot. Crammed into sweat shops, mills, mines and factories, workers grew restive, demanding better wages and conditions and sometimes going on strike.

At the other end of the spectrum, the wealthy of America were no longer simply the owners of large plantations and estates. They were a new breed of businessmen called "merchant capitalists" and "industrialists," people whose wealth was in stocks and bonds rather than property. There were plenty of domestic tensions revolving around economic issues. Farmers and workers regarded the wealthy new class of bankers, lawyers, merchants and speculators as "capitalists" and "bloodsuckers." On the whole, however, Americans were a prosperous people, even though they endured many cycles of boom and bust. Their average income doubled in a half century, and they could afford to buy goods that once had been transported by small ships and flatboats and now arrived on large ships and by roads and rail. New canals and railways enabled farmers to produce and sell their food in what had become for the first time a national market for goods. A revolution in communications allowed news to travel by telegraph. Newspapers and magazines were read by a growing middle class.

Few Americans doubted that these good times were the product of the hard work, industriousness and thrift of the most blessed new citizens of the world. But because there was now a national marketplace, the federal government stepped in to play a critical role by chartering the banks, licensing the corporations, digging the canals and sponsoring the railroads that laid a foundation upon which the nation could grow. To carry out these functions at the federal level required revenue. But on the eve of the Civil War, Americans were not used to paying anything to support their national government except indirectly, through the tariff. The federal excise tax on alcohol had been repealed in 1817. In the 1850s, the federal government obtained 92 percent of its revenues from customs duties imposed on goods imported from abroad. While protecting domestic industry from competing with cheap imports, the tariffs raised the price of nearly all goods consumed by Americans, from clothing to farm equipment. It was the tariff that paid America's way, which is why it was for so long so contentious an issue in American politics.

Tariffs were like a silent sales tax. Though regressive in nature, falling more onerously on the poor than on the rich, tariffs were accepted by Americans because they shared a broad assumption that everyone, producer and consumer alike, gained materially from the government's role in nurturing domestic industry and jobs. Indeed, without tariffs, the United States would have made a much slower transition from its status as a nation with an agrarian-based economy, rich in resources but lacking in capital investment, into the mighty industrial power it became after the Civil War. Debates about the tariff rose and fell throughout the nineteenth century, but without significant damage to the broad consensus in their favor. Democrats supported what Andrew Jackson termed a "judicious tariff," while Whigs, and later Republicans, pushed for higher tariffs to protect industries to fulfill their vision of development and enrich their political base. In the 1840s and 1850s, the anti-tariff forces managed to keep trade barriers reasonably low. Then came the Panic of 1857, a calamitous recession, after which Republicans succeeded in enacting the higher tariffs that they argued were needed to protect jobs and industry from foreign competition.

These were some of the economic conditions on the eve of the Civil War. By the end of the conflict, the Union demand for money to prosecute the war sent tariffs to record levels. American citizens paid higher prices for virtually everything they purchased. To persuade Americans that the wealthy citizens who were prospering from the war would bear more of its cost, Congress and the President turned in 1862 to the income tax, as well as taxes on corporations. Taxes, for the first time, were imposed on people's incomes, at graduated rates. A new bureaucracy was established to collect these charges, the Internal Revenue Bureau.

Taxpaying in wartime, when sacrifice is demanded from everyone, is shouldered more willingly than in times of peace. During the Civil War, it was borne to save the Union and free the slaves. And for the first time, taxation was also conceived and understood as an instrument that reduced inequality in a time of economic upheaval, when new fortunes were being made, in part out of war profits. As one lawmaker put it during a heated tax debate in the House, referring to two families that had grown rich during the war: "Go to the Astors and Stewarts and other rich men of the country and ask them if in the midst of a war [the income tax] is unreasonable. I could not advocate anything else in justice to the middle classes of the country."

To many visitors who traveled to Springfield after the 1860 election, Abraham Lincoln seemed overwhelmed.

The President-elect had an unsettling habit of pledging firmly to protect the Constitution and then throwing in a stream of jokes and homespun anecdotes. As the news arrived of one state after another seceding, he was noncommittal about what he planned to do. He had just won a precarious victory with less than 40 percent of the popular vote, and many people around him wondered whether he was up to the challenge of preserving the Union. At the beginning of this strange period of testing, Lincoln, perhaps reflecting some kind of private uncertainty about himself, surprised his friends by suddenly growing a beard.

For all his historic majesty, Lincoln in retrospect is a figure of puzzling contradictions. He was a man of action with doubts about the efficacy of action, a fatalist and an idealist, a farsighted thinker who could be slippery and reactive. We think of Lincoln as a great visionary, but he came across to many of his colleagues as pragmatic. "My policy is to have no policy," he said. The biographer David Herbert Donald attributes to Lincoln in action that quality defined by Keats as "negative capability," the ability to live with uncertainty, doubt, mystery and the avoidance of "any irritable reaching after fact and reason." Yet he could come to a sharp decision when history required.

Lincoln's economic views are more easily definable, but they, too, derived from a mixture of high principle, philosophy and practical politics, as well as from lessons that he had learned from his own life's varied experiences. Long before the war, starting at least when he was in his early twenties, these views embraced rugged individualism and aggressive government -- a belief that capitalism rested on both the dignity of labor and state intervention. As the biographer and historian Gabor S. Boritt notes, his image was tailor-made to represent the virtues of hard work in a free society. His nickname, "the Rail Splitter," harkened back to "Old Hickory" for Andrew Jackson and "Tippecanoe" for the war hero William Henry Harrison of the "Log Cabin" campaign of 1840. But it mainly helped Lincoln project himself as a classic self-made man, whose industry would be as good for the country as it had been good for his own soul. He had been a riverboat pilot, country store clerk, soldier, merchant, postmaster, blacksmith, surveyor, small town lawyer and then big business lawyer representing railroads and other powerful interests in the new corporate America.

Lincoln was a philosophical exponent of Henry Clay's so-called "American System," which was rooted in the theories of the first Treasury Secretary, Alexander Hamilton, and which consisted of tariffs to protect industry, a national bank and government spending to promote "internal improvements," from canals to roads to railroads. By investing in these projects, the government would help link the manufacturing of the Northeast to the grain production of the West and the cotton and tobacco production of the South, bringing wealth to all. Clay called the American businessmen thriving in such a system "self-made men," but the term had obvious limits. Government spending on public works and government actions to erect tariff walls around industry clearly gave the meaning of "self-made men" a kind of spin. Call it public improvements or call it pork barrel: Lincoln was good at it.

As a state lawmaker, he fought to bring state money home to his district to improve the Sangamon River near his community of New Salem, Illinois, which was near Springfield, the city that was to become the capital of Illinois, also with his lobbying. To demonstrate that the Sangamon was navigable, Lincoln one day waded into the river, cut back the brush and then took the helm of a visiting steamer to prove his point. In the legislature, he also came up with financial schemes to support dredging, clearing muck and brush from riverbanks and gouging out canals in his part of the state, including a channel to link Lake Michigan to the Mississippi via the Illinois and Chicago Rivers, a project hailed as rivaling the Erie Canal in economic importance. He advocated state debt or the sale of state land to raise money for such projects -- even the purchase of federal land followed by its resale to settlers, using the profit for the improvement needed to get his home district's goods to world markets. The historian Gabor Boritt, surveying Lincoln's economic philosophy from its early days, notes the "striking contrast" in his voting for expensive river projects but squabbling over small amounts of money in the regular state budget. "Penny-wise and pound-foolish," says Boritt, "he acted almost as though possessed by a dream."

Public improvements were so vital to Lincoln's philosophy, and to the future of the region he represented, that he even supported -- "reluctantly," according to David Herbert Donald -- increasing taxes on property, which were the main source of revenue for state and local governments at the time. Not just taxation but taxation with a higher rate for those with higher property values, rather than a flat tax with the same rate for rich and poor alike. He told the Illinois legislature that the graduated tax scheme was "equitable within itself" because it would fall on the "wealthy few" who, "it is still to be remembered...are not sufficiently numerous to carry the elections." The tax, however, was not adopted.

By the time Lincoln arrived in Congress in 1847, many of the old economic issues of his early public career had grown passé. President James K. Polk, a Democrat, reduced tariffs to new lows, vetoed several internal improvements measures and presided over the war with Mexico, which was about to add California and New Mexico to the Union. Like other members of the Whig Party, forerunner of the Republican Party, Lincoln opposed the war. He then turned around in 1848 to support the presidential nomination of the soldier who had helped win it, General Zachary Taylor. Lincoln lined up with those Whigs who were opposed to a strong presidency, a stance that would come back to haunt him.

Lincoln honored an informal agreement among rival Whig Congressional aspirants in his home county by retiring after only one term in Congress, returning to his law practice and thinking that his public career was probably at an end. It was as a lawyer that he became known as "Honest Abe," the brilliant courtroom practitioner with a deceptive cracker barrel style and a comfortable income of $2,000 a year, which put him in the top 1 or 2 percent of Americans. He owned $5,000 in real estate and a personal estate of $12,000. Increasingly his practice was taken up with legal problems of the railroads, which he supported as an agent for economic growth.

Slavery was something Lincoln had always opposed as wrong but preferred not to act on, though he sponsored antislavery resolutions as a young legislator and advocated the shipment of slaves back to colonize Africa. But along with the new antislavery group, the Republican Party, Lincoln began to challenge the expansion of slavery to the new territories of the West and to develop his tone of moral outrage. In debates, he stood straight at 6 feet 4 inches, sometimes bending down in a crouch for dramatic effect. His style and eloquence drew the attention of party leaders, who briefly considered him for the 1856 vice presidential nomination. It was Lincoln who contributed the idea of making a party motto out of Daniel Webster's old rebuke to the doctrine holding that states could nullify high tariffs, the forerunner to secessionism: "Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable."

By the time of his 1858 race for the Senate against Stephen A. Douglas, Lincoln had left his early economic issues behind. The Lincoln-Douglas debates did not address bank regulation, tariffs, immigration, homesteads for farmers or the improvement of factory wages and conditions, the staples of Republican politics since the party's founding a few years earlier. Instead, they argued over slavery, which Lincoln proclaimed to be "a moral, social and political wrong."

Lincoln lost the Senate election but became known across the country as the eloquent advocate of opposition to the expansion of slavery into the American territories and as the leading Republican statesman from Illinois. His only significant rival from the Midwest as a potential national party leader and future presidential nominee was Governor Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, whose delegates defected to Lincoln and helped him capture the 1860 nomination. By the election, slavery was the central issue. But Lincoln's opposition to slavery was a subtle thing, based not simply on moral principle but also on politics, experience and longtime economic philosophy.

Since its founding in 1854, the Republican Party opposed slavery as more than a violation of God's commands. It was seen as a threat to the system of "free labor" and capital responsible for American economic growth, wealth and world influence. Lincoln agreed at all levels. He was a great moralist, to be sure, but he was also a fierce exponent of the so-called labor theory of value -- the idea that an individual's ability to work is the foundation of the economy and that the accumulation of capital rests on labor. He believed that "free labor" was sacred not only because it produced wealth but also because it allowed workers to become owners and capitalists -- to become wealthy, as he had. Lincoln saw himself as the embodiment of the spirit of individual enterprise. He paid little attention to the increasingly obvious fact that factory workers in growing numbers were mired at the bottom end of the ladder, unable to rise above their station. Lincoln's philosophy was summed up by his statement that wealth automatically accrues when "the prudent, penniless beginner in the world labors for wages awhile, saves a surplus with which to buy tools or land for himself; then labors on his own accounts another while, and at length hires another new beginner to help him."

Campaigning in 1860 in New Haven, Lincoln said, "I am not ashamed to confess that twenty-five years ago I was a hired laborer, mauling rails, at work on a flat-boat -- just what might happen to any poor man's son!" The miracle of the system, he declared, was that "there is no such thing as a freeman being fatally fixed for life, in the condition of a hired laborer." From this came the staunch Republican philosophy, delineated by the economists Francis Wayland and Henry Charles Carey, that it was God's law to enable men to work, gain wealth and accumulate private property -- and that it was the government's obligation to create and protect the conditions under which men could do so. Capitalism, in this view, was not a selfish philosophy. Rather, it created the conditions for a benevolent society in which the virtues of thrift, hard work, ambition and selflessness would triumph over savagery and yield higher living standards for everyone.

This economic philosophy, the bulwark of the argument against slavery, leads to a skeptical if not hostile perspective toward taxes. Taxing wealth as wealth would later be seen by the exponents of "free labor" as an assault on the very incentives on which the hopes of Western civilization were pinned. That sort of thinking would become clear in due course. For some years now, insofar as they addressed economic issues, Democrats had countered the Republican philosophy of harmony between workers and capitalists with their own view that conflict between the two was inevitable. Indeed, Democrats saw government intervention in the economy through tariffs, public improvements and the like as nothing more than corrupt aid intended to support rapacious monopolies of power and wealth. They clung to this philosophy for some years, though the economic debate was engulfed in 1860 by the issue of slavery and the prospect of civil war.

From the perspective of today, we can see that faith in prosperity has been the abiding theme of Republicans for 150 years. In the years before and after the Civil War, however, Republicans believed that the federal government had a crucial role to play in nurturing wealth. Accordingly, the platform on which Lincoln ran called for a better homestead act to please western farmers and federal aid to improve rivers and harbors to appeal to Detroit, Chicago and the burgeoning cities of the Great Lakes region. Perhaps most important, to placate the fledgling manufacturers of the Northeast, who were struggling to compete with cheaper goods manufactured abroad, the platform urged a higher and more protective tariff. The tariff would effectively raise prices on clothing, farm equipment and many other everyday necessities. Farmers in the South and West, squeezed by these high prices and struggling to sell their own farm products abroad, protested the high tariff. With their electoral clout, they had managed to keep duties relatively low for the two decades leading up to the Civil War.

Tariffs were not called taxes per se, but that is what they were, and what Americans understood the tariff system to be. Tariffs were the main source of federal revenues, and with the victory of Republicans in 1860, Congress and the President were likely to use tariffs to return to the "American system" in which business prosperity was seen as good for everyone.

These were some of the factors that thrust Lincoln to the threshold of the most violent and transforming presidency in American history. None of them prepared him for the crisis he faced as most of the slave states announced that they were seceding from the Union and began seizing federal arsenals within their borders.

South Carolina went first.

The state's grievances had been long-standing and not simply focused on slavery. Its major complaint went to the heart of the nation's finances -- tariffs. A generation earlier, South Carolina had provoked a states' rights crisis over its doctrine that states could "nullify," or override, the national tariff system. The nullification fight in 1832 was actually a tax revolt. It pitted the state's spokesman, Vice President John C. Calhoun, against President Andrew Jackson. Because tariffs rewarded manufacturers but punished farmers with higher prices on everything they needed -- clothing, farm equipment and even essential food products like salt and meats -- Calhoun argued that the tariff system was discriminatory and unconstitutional. Calhoun's antitariff battle was a rebellion against a system seen throughout the South as protecting the producers of the North. The crisis was defused with the help of Henry Clay of Kentucky, former House Speaker, and later senator, three-time presidential candidate and passionate advocate of preserving the Union, who persuaded South Carolina to yield on nullification in return for gradually reduced tariffs.

But now the issue was slavery, and there seemed to be no backing down.

Within a day of Lincoln's election, South Carolina, fearing that Lincoln would outlaw slavery in the territories and eventually the South, summoned a state convention to decide what to do about the voters' verdict. In December, the convention voted to secede, and within a month and a half, five more states followed. Soon only a handful of federal installations in the South remained in Union hands. The sitting President, James Buchanan, was not opposed to slavery, but he repeatedly asserted that the federal government could not tolerate the seizure of its property, including the customs houses that collected the tariff revenue on which the government's finances were based. To better defend himself in South Carolina, Major Robert Anderson moved his small garrison on the shoreline at Charleston to Fort Sumter, on a rocky shoal in the harbor. Though Buchanan denied South Carolina's right to secede, he also would not use force to stop it. Instead he sent an unarmed ship, The Star of the West, with arms and additional troops to reinforce the fort. After being fired on, it steamed away.

From his base in the governor's office in Springfield, Illinois, President-elect Lincoln found himself consumed with doling out patronage and balancing political interests in forming his cabinet. Lincoln was not simply a stranger to most Americans. He was the first Republican to be elected President and an unknown quantity to the political satraps and brokers in Washington and the big northern states, all of them eager for the federal jobs and contracts enjoyed by the Democrats for the previous eight years.

Lincoln left Springfield on a cold and rainy February 11 for the twelve-day, 1,904-mile journey east to the nation's capital. On the last leg of the trip, from Harrisburg and Philadelphia to Washington, word arrived that someone would try to murder him. Lincoln reluctantly agreed to sneak into the nation's capital from Baltimore disguised in a fake hat and cape, thus opening his presidency on a note of ridicule and perceived cowardice. Yet Lincoln's inaugural was firm and majestic. It sounded a note of economic necessity as well as moral principle by promising "to hold, occupy and possess the property, and places belonging to the federal government." More memorably, Lincoln spoke of his optimism that "the mystic chords of memory" would save the Union when "touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature."

At the first state dinner shortly after the inauguration, the President kept up the flow of anecdotes and witticisms. Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase recalled later that he felt impatient with Lincoln's casual behavior until after dinner, when the cabinet withdrew to a private meeting and heard the bad news from a suddenly not-so-cheerful President. Earlier optimistic reports from Fort Sumter were wrong, they learned. Far from having enough supplies to last weeks or months, the garrison was about to run out of food, and from the scene Major Anderson was warning that it would take 20,000 men to secure the besieged fort. The astonished cabinet was divided about what to do. The Secretary of State, former senator and governor William Seward of New York, favored evacuation, and Chase vacillated.

Lincoln decided that Sumter had to be relieved -- peacefully, with unarmed tugs and whaleboats. On April 12, rebel forces under General Pierre G. T. Beauregard opened fire on the fort. Anderson returned fire, and on the following Sunday, April 14, he surrendered, hauling down his flag as Beauregard's forces took over and permitted the Union troops to embark for New York. As Lincoln had hoped, if there had to be a first shot, it was the secessionists who fired it. The Civil War had begun.

As South Carolina's forces took control of the fort, Chase was discovering that there was no money in the Treasury to fight the war. Though America had grown to become a mighty economic power, and though the North's wealth was several times that of the South, its economy was in dire shape. The Panic of 1857 had ended a dozen years of growth. It struck after a period of prosperity accompanied by higher prices, speculation and increasing powers accruing to the nation's banks. Rising prices had resulted also from a surge of grain exports to Europe as American farmers suddenly filled a gap when Russian grain was cut off in the Crimean War. Like many other "panics" of the early days of capitalism, the Panic of 1857 began with the disclosure of an embezzlement scheme -- this one in the New York branch of an Ohio investment company. The ensuing wave of alarm set off a run on the banks, selling on Wall Street, a suspension of gold and silver payments by banks, falling prices, declining trade and a government saddled with deficits and debts. In boardrooms and government offices, worker protests stirred fear of European-style class warfare. A mob stormed the United States Customs House on Wall Street, threatening to break in.

Economic experts gave many reasons for the sudden collapse in the nation's economic fortunes. But Republicans singled out two major factors. The first was the virtual nonexistence of a federal banking system after President Andrew Jackson killed the federal charter of the privately operated Bank of the United States in 1832. The second factor, said the Republicans, was the low tariffs adopted under pressure from the Democrats in 1846 and again in early 1857. Hard times often breed demands for higher tariffs, and well before the Civil War, Republicans insisted on raising duties to protect ailing industries -- especially those, like the devastated iron and steel works of Pennsylvania, represented by powerful members of Congress. Supporters promoted tariffs as a way to expand employment so that Americans wouldn't have to compete with the "pauper labor" of Europe. But the Democrats saw tariffs as a cudgel to subsidize wages and profits in the North at the expense of consumers, especially in the South. The South wasn't as hard hit in the Panic because its farmers could continue exporting cotton while enjoying the ability to import farm equipment from England under the tariffs that had been lowered in the previous twenty years.

The Panic of 1857 devastated the North in several ways. The national income plummeted to $4.3 billion, or $140 per capita, drying up savings that might otherwise have been able to finance government borrowing. Tariff revenues declined because Americans were unable to pay for imports. Borrowing of any kind by the government required Congressional authorization. But there was no central bank -- indeed, no strong banking or unified currency system -- to make borrowing practical. The banking system consisted of some 1,600 state banks, each operating independently. Some 7,000 different kinds of bank notes circulated, more than half of them bogus. The value of these currencies depended on the solvency of each bank, so that a $10 bill from a bank in Maine might be worth only $8 in Boston or $5 in New York. The government used only hard currency backed by gold, so there was in effect a dual-currency system. ("Gold for the office holders," went the public refrain. "Rags for the people.")

The onset of hostilities in 1861 made all these conditions worse, sending customs receipts plummeting and forcing investors to renege on their commitment to buy government bonds. The banking system at large was in chaos as debtors in the South threatened not to honor their debt repayments to northern banks. Indeed, they were withdrawing their deposits. Lower tariffs and the economic slowdown reduced federal revenues, resulting in federal deficits and deficit projections as far as the eye could see. "The treasury was empty," John Sherman, then an Ohio senator and younger brother of the future Union general William Tecumseh Sherman, later wrote in his memoirs. "There was not enough money even to pay Members of Congress."

The man chosen to deal with these problems was unapproachable, dour and suspicious of others, with a big bald head that some said seemed to radiate intelligence. Salmon P. Chase was a deeply religious man who quoted the Scripture in conversation, liked to recite psalms while bathing and dressing and tended to express his views as dogma. He was also a firm opponent of slavery who believed that abolition was a moral imperative fulfilling the implicit wishes of the nation's founders.

After two terms as governor of Ohio and after losing the Republican nomination to Lincoln, Chase prepared to take his place in the United States Senate, where he felt he could best help the new President face the daunting challenges ahead. That was before the President-elect, a man he had never met, asked him to pay a call in Springfield, Illinois. Ever solicitous, Lincoln came to see him at the hotel when he heard that Chase had just come into town after traveling two days in cramped cars in four railroads from Columbus. Chase later recalled that he had been extremely reluctant "to take charge of the finances of the country under circumstances most unpropitious and forbidding." But Lincoln was impressed with his political skills, declaring that he seemed to be "about one hundred and fifty to any other man's hundred" -- a remark that was not seen as especially extravagant in its praise. He nonetheless needed someone of strong intellect and experience to face the biggest financial challenge since Alexander Hamilton rescued an infant nation from insolvency after the Revolutionary War.

Facing his initial problems, Chase had to educate himself and study how to come up with legislation to deal with the crisis. He had some familiarity as a lawyer and former director of various banks. He was a "convinced hard-money man," but that did not mean much in the face of a gigantic financial crisis that included $75 million in debts. More than a third of the debt was in so-called unfunded Treasury notes, which meant there would be no money to repay them when they fell due in less than a year. The notes were considered nearly worthless in the marketplace. Chase reported that they were being traded at "ruinous" discounts.

Under the law as enacted by Congress, Chase had the authority to issue up to $40 million in long-term government bonds at a rate of 6 percent. Also, Congress had raised tariffs before Lincoln's inauguration to try to stem the tide of red ink. In an atmosphere of patriotic fervor after Fort Sumter, many in Washington hoped that Americans would come to the aid of their country by buying bonds. But given the insecurity of the nation's finances, the proposed interest rates on federal debt proved too low to attract customers. Financial markets in this period were engaged in the buying and selling of debt rather than equities. To find purchasers for United States bonds, Chase had to relax the interest rate requirement, selling them at a discount. He also had to resort to still more short-term notes, a risky expedient because the government had to refinance the notes as they fell due a few months later. His hope was to use cash on hand and postpone bill payments to tide the government over until July, when a special session of Congress was scheduled.

In response to Lincoln's emergency summons, Congress convened on July 4, two-and-a-half months into the war. By then Chase had made his first estimate of the war's cost, but it was conservative if not timid. Looking ahead, he forecast that the war would cost $320 million. He proposed $240 million to come from loans and $60 million from revenues from land sales and tariff increases on commodities like sugar, tea and coffee. The remaining $20 million was to come from unspecified taxes. Many economic historians judge the package shortsighted and inadequate. In his 1942 study of American taxation, Sidney Ratner, a pre-eminent scholar of the subject, describes Chase's approach as overly "moderate and cautious." Taxing wealth in any direct fashion was not on Chase's agenda, however. Indeed, he still hoped that any new taxes would last only a year. Congress eagerly adopted Lincoln's proposal to field an army of 400,000 men. The lawmakers actually improved on his request, setting plans to send 500,000 men into battle. Their interest in raising taxes and borrowing was less enthusiastic. Congress ended up authorizing $250 million in notes or bonds, while the revenue-raising measures remained mired in debate.

Any hope that Congress's action on tariffs would be adequate proved to be short-lived, however. It died in a forested and hilly section of northern Virginia, not far from Washington, D.C., near the town of Manassas and the river a few miles to the north called Bull Run.

Copyright © 2002 by Steven R. Weisman

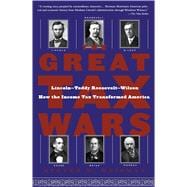

Excerpted from The Great Tax Wars: Lincoln--Teddy Roosevelt--Wilson and How the Income Tax Transformed America by Steven R. Weisman

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.