Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

Tracy Daugherty's work has appeared in the New Yorker, McSweeney's, The Georgia Review, and others. He has received fellowships from the NEA and the Guggenheim Foundation. Once a student of Donald Barthelme's, he is now Distinguished Professor of English and Creative Writing at Oregon State University.

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

Tools

The America that Don knew as a boy and as a teenager, in the 1930s and 1940s, was a nation whose structures were beginning to be formed with messianic fervor. Or so his father believed. His father, Donald Barthelme, was born in Galveston, Texas, in 1907, the son of a lumber dealer. He learned, early, to calculate board feet, negotiate timber rights, and distinguish loblolly from other sorts of pine trees. These skills led him to a pragmatic view of building and of problem solving in general, a view his eldest son would inherit.

During the elder Barthelme’s childhood, Galveston was dominated by singular personalities who left indelible imprints on the city’s finances, institutions, environment, and cultural life. William Lewis Moody, Jr., the son of a cotton magnate, owned controlling interest in the city’s national bank; in 1923, he purchased the Galveston News, Texas’s oldest continuously running newspaper; in 1927, he formed the National Hotel Corporation, and subsequently built two of the city’s landmark inns; he organized what became the biggest insurance company in Texas, and bought a printing outfit and several ranches, though he had little interest in raising cattle. He used the land for duck hunting and fishing. A Gulf Coast Citizen Kane, he managed the city’s money and information, and shaped much of the public space. In 1974, Don would publish a story called “I Bought a Little City” about a Moody-like man who, otherwise bored with his life, establishes an amiable but unimaginative empire in Galveston, and presides over the city’s decline.

The other major figure in town, prior to World War I, was N. J. Clayton, a supremely confident architect with a love of high Victorian style. Even today, the generous loft spaces in many of Galveston’s commercial buildings bear his mark. He favored bold massing and articulate composition, and was fond of Gothic detail. That one man’s sensibility, if pushed aggressively, could fashion a city’s looks was a lesson absorbed, and cherished, by Barthelme senior. It was an example of idealism, optimism, and hard work that he impressed on his children.

Always short for his age, with red hair, fair skin, and fat glasses from the time he was three, the elder Barthelme felt as a boy that if he was going to get anywhere in life, he “wasn’t going to be able to just stand there.” “I had to walk into a room with a swagger, and talk loud, and tell ’em I was there,“ he said. In their memoir, Double Down, his sons Rick and Steve said that, early on, their father adopted the attitude, perhaps modeled on men like Moody, that the “world was a place that needed fixing and he was just the man to fix it.”

By the time he reached high school, he was an assured and popular young man, always tweaking authority to win his friends’ loyalty, practiced at the swagger he’d affected, a hell-raiser.

As a college freshman, he enrolled in the Rice Institute, in Houston, but was asked to leave “for some indiscretion in the school newspaper, which he edited,“ Rick and Steve recounted, “an indiscretion that wasn’t his, as it turned out, but some fellow student’s for whom Father was taking the fall.”

The elder Barthelme’s father approached school administrators on his behalf but found them unbending. Instead of waiting twelve months to reenroll, when his suspension would expire, Barthelme transferred to the University of Pennsylvania. There, he studied architecture with Paul Philippe Cret, and he met Helen Bechtold, whom he would marry in June 1930. They were introduced on a blind date when he went with a buddy to Helen’s sorority house. As Helen and a friend approached the boys in the house’s foyer, Helen whispered that she hoped she would get the “tall, dark, and handsome one.” Instead, her date was the “short, red-headed one.”

“He was a fortunate man,“ Rick and Steve wrote in Double Down. “[Mother was] a prize that took some winning, according to the family lore, for while Mother was smart, talented, stylish, attractive, and sought after, our father was only smart and talented.” Away from school, Helen lived in Philadelphia with her mother and sister. Her father had died when she was twelve, leaving his family financially secure, but Helen wanted a teaching career and even made what she once described as an “abortive attempt” at writing. She was interested in acting at the time she met Barthelme.

On April 7, 1931, Don was born (he would later write, “What else happened in 1931?...Creation of countless surrealist objects”).In December of 1932, his sister, Joan, arrived. Helen Bechtold Barthelme abandoned her teaching, writing, and acting dreams; she hunkered down to become the “beloved mother” of a family that would eventually total five children, all of whom, swayed by their mother’s love of reading and drama, excelled at writing.

After graduating from Penn, Donald Barthelme, Sr., worked as a draftsman for Cret and for the firm of Zantzinger, Borie, & Medary (where he helped design the U.S. Department of Justice building in Washington, D.C.), but he was unable to find lasting work in Philadelphia. In 1932—just before Joan was born— the family moved to Galveston, where Barthelme joined his father’s lumber business. The company was best known for building a magnificent roller coaster near the seawall at the beach. Barthelme’s father, Fred, a New York transplant, was a prominent and successful member of Galveston society.

Barthelme was restless working for the old man and living in a garage apartment behind his parents’ house. He worked briefly for the Dallas architect Roscoe DeWitt, then, in 1937, moved his family to Houston, where he joined the firm of John F. Staub. In 1940, he branched out on his own.

At Penn, his course of study had stressed traditional architecture and conventional building techniques. On his own, he studied the Bauhaus movement in Europe and pored over Frank Lloyd Wright’s published plans; still, he didn’t chafe against Penn’s established pedagogy. He admitted his perplexity at the Philadelphia Savings Fund Society building, designed by Howe and Lescaze— this was one of most prominent modern buildings erected in the United States in the 1930s, and Barthelme didn’t get its austerity.

In Philadelphia, he encountered, once more, powerful personalities. In class one day, evaluating one of Barthelme’s designs, Cret asked, “Where did you get this idea?” “Oh,“ Barthelme said, “I got it out of my head, Mr. Cret.” “It’s good that it is out,“ his teacher replied. Temporarily, Barthelme worked for Cret in a Philadelphia firm that employed Louis Kahn. At night, Kahn would go around the office and leave critiques on his coworkers’ designs, including those of his bosses. People “laughed at him,“ Barthelme said. “But he was teaching himself.”

Little by little, Barthelme taught himself modern architecture. He would pass his enthusiasm for learning on to Don. Though Don’s chosen pursuit would differ from his father’s, the idea of the modern and the aesthetic principles of modern architecture form the background of Don’s writing. A broad familiarity with what was at stake in his father’s world is essential to understanding what mattered to Don in his work.

Paul Philippe Cret, Barthelme’s mentor at Penn, accepted a teaching position at the university in 1903, which he held until his retirement in 1937. He studied at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, one of Europe’s oldest centers of art and architectural education, dating back in various forms to 1671. The Beaux-Arts basic design principles stressed symmetry, simple volumes, and lucid progression through a series of exterior and interior spaces; the outside was a rational extension of the inside. Beaux-Arts urbanism relied on visual axes with clearly marked meeting points as its prime ordering device; its most celebrated examples were Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s schemes for the reorganization of Paris in the mid-nineteenth century. The Beaux-Arts approach was not seriously challenged in American academia until the late 1930s, when a second wave of Europeans came to the States, who were advocates of the International Style, and assumed positions of power.

As Cret’s career progressed, he absorbed elements of the International Style and began a process of simplification, minimizing the ornamentation of his designs. He reduced the number of moldings, which served to highlight the planar and volumetric quality of his work. Many of his earlier designs, such as the one for the Indianapolis Library, used Doric colonnades. By the early thirties, when he conceived the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., he had replaced the colonnades with abstract fluted piers.

At a time when university architecture departments felt the first ripples of a change, when, more than ever, competing ideologies dominated the field, Barthelme was excited to find a man like Cret, who bridged the gap between tradition and innovation. Cret was not bullying or domineering, but he was unflappable and firm. These qualities enabled him to perform the architect’s trickiest task smoothly: appeasing prickly clients and warring constituencies. He could “cut through” the politics, bad histories, “complexities and ambiguities” of a situation, wrote Elizabeth Greenwell Grossman, and “offer a design that seemed by its simplicity to reveal the immediate character of [an] institution.”

Initially, Barthelme followed this example to good effect, but calm, compromise, and diplomacy were not attributes he could sustain. Eventually, he would topple into the “excesses” of his profession, the “heroics and mock-heroics” exhibited by architects in general, as Don later reflected.

What came to be called the International Style of modern architecture, in the years between the first and second world wars, valued lightweight materials, open interior spaces, smooth machinelike surfaces, and exposed structural components, airily clad in collaged metal sheeting or glass curtain walls. It was a craft test-driven in the Bauhaus workshops in Germany in the 1920s under the direction of Walter Gropius, who championed austerity and performance in the steel windows and door frames of the houses he designed, in exposed metal radiators, exposed electric lightbulbs, and elemental furniture. He believed that materials and forms should be celebrated for their independent, asymmetrical structures, rather than for their compatibility and relative invisibility in an overall design.

In the Bauhaus vision, all the arts joined to shape a splendid future. “Together let us conceive and create the new building...which will embrace architecture and sculpture and painting...and which will rise one day toward heaven from the hands of a million workers like the crystal symbol of a new faith,“ said the group’s 1919 proclamation. Beneath the document’s socialist zeal, one can still hear the trauma of war, and an uncertainty about whether any social order can survive the erosions of time and the violence of men.

The Parisian architect Le Corbusier expanded the Bauhaus model, promoting “house machines,“ “healthy (and morally so too) and beautiful,“ he said, “in the same way that the working tools and instruments which accompany our existence are beautiful.” Mies van der Rohe, who began his career in Berlin, expounded a skin and bones architecture in the office buildings he designed. “The maximum effect with the minimum expenditure of means,“ his projects proclaimed.

The schools of modern architecture were not uniform, nor were their practitioners always in agreement, but the field’s leading figures shared a belief that architecture should boldly reflect its time. Convictions about the character of the time conflicted wildly, but this did not blunt the energy with which Gropius, Le Corbusier, Mies, and others set out to convert the world to their aesthetic aims. They were on a crusade. As large-scale turmoil scarred Europe more and more in the first half of the century, the tenor of the time, and appropriate responses to it, became harder to parse. One could argue that the only sane response to the Holocaust was emptiness and silence—not to build at all. But Europe’s upheavals had another effect: the flow of brilliant architects to the safety and relative openness of the United States, which Le Corbusier called the “country of timid people.”

If U.S. institutions were slow to accept the new architecture, young architects in the nation’s finest programs, schools, and firms were not at all timid about embracing change. A “tendency toward Oedipal overthrow” has always been “rampant in [the] profession,“ says the architecture critic Herbert Muschamp. To survive, one must cultivate a strong personality.

During this pivotal migration of genius, Donald Barthelme, Sr., started his practice. Since childhood, he had worked to overcome timidity, to prove himself by staking out fresh directions. Later in life, he recalled meeting, early in his career, Mies van der Rohe, and criticizing one of the master’s buildings for its lack of human scale. “Mr. Barthelme, I find that I can make things beautiful, and that is enough for me,“ Mies replied.

Barthelme’s first major projects straddled the battle zone between the future and the past. Zantzinger, Borie, & Medary’s design for the U.S. Department of Justice building, which Barthelme had a say in (though, as a junior member of the team, not a very large one), combined classical style with Art Deco detailing and an unusual use of aluminum for features commonly cast in bronze, such as interior stair railings, grilles, and door trim.

After his return to Texas, Barthelme inherited a project begun by Frank Lloyd Wright, which struck an early modernist blow in Dallas. The entrepreneur Stanley Marcus had commissioned Wright to build a house on six and a half acres of north Texas prairie. Marcus recalled:

We had told Mr. Wright that we could only afford to spend $25,000, which was a lot of money in the Depression year of 1934, but which he assured us was quite feasible.We invited him to come to Dallas....He arrived on January 1, with the temperature at seventy degrees. He concluded that this was typical winter weather for Dallas, and nothing we could tell him about the normal January ice storms could ever convince him that we didn’t live in a perpetually balmy climate. When his first preliminary sketches arrived, we noticed that there were no bedrooms, just cubicles in which to sleep when the weather was inclement. Otherwise, ninety percent of the time we would sleep outdoors on the deck. We protested that solution on the grounds that I was subject to colds and sinus trouble. He dismissed this objection in his typical manner, as though brushing a bit of lint from his jacket....

Additionally, Wright provided “little or no closet space, commenting that closets were only useful for accumulating things you didn’t need.” Frustrated, Marcus enlisted Roscoe DeWitt to serve as a local associate for Wright, who had returned to Taliesin, and to be an on-the-ground interpreter of Wright’s plans. Marcus clashed again with the great man when he asked DeWitt to be on guard against inadequate flashing specifications—Wright’s buildings were notoriously leak-prone, but he deeply resented this precaution.

Bad feelings got worse, cost estimates spiraled, and, eventually, Marcus turned everything over to DeWitt and his young designer, Donald Barthelme. “I couldn’t understand [Wright’s] plans,“ Barthelme said. “He had a column that was in the shape of a star, and he had marked a little note that said, ‘stock column.’ So far as I knew there was no such stock column. He also had six panes of glass about six feet wide each that were slipped into adjacent tracks with no frame around the end. I can just imagine trying to slide those doors open.”

Ultimately, the house, completed in 1937, bore no resemblance to Wright’s initial design. Barthelme designed a long, low-lying structure with cross ventilation and open living and dining rooms. Pronounced overhangs sheltered the windows. The result was too conventional to be a notable piece of architecture, Marcus said later, though it was unconventional enough to be “highly controversial” in Dallas at the time. “It proved to be a home which met our living requirements better than the Wright house would have done.”

That same year, for the Texas centennial celebration in Dallas’s Fair Park, Barthelme designed the Hall of State, which remains among the most monumental structures in Texas, and was then, at $1.2 million, the most expensive building per square foot ever constructed in the state. Originally, a consortium of ten Dallas firms had been hired to create the hall, but they failed to produce a plan acceptable to the State Board of Control. Barthelme synthesized their ideas and added his own. Faced with Texas limestone, with bronze doors and blue tile (the color of the bluebonnet, Texas’s state flower), the building is an inverted T—a structure in which Paul Cret’s influence is apparent.

Barthelme assembled a team of regional, national, and international artists to add Art Deco touches to the Hall of State. He conceived a symbolic seal of Texas to hang above the entrance, depicting a female figure, the “Lady of Texas,“ gripping a shield and the state flag. Beside her, an owl, representing wisdom, perches on the Key of Prosperity and Progress. On the frieze around the building, near its top, the names of fifty-nine legendary Texans are carved. The first letters of the first eight names, reading left to right—Burleson, Archer, Rusk, Travis, Higg, Ellis, Lamar, and Milam—spell the architect’s name, minus only the final e. A playful touch, a buried secret: These would become hallmarks of his eldest son’s art, as well.

John Staub, for whom Barthelme worked from 1937 to 1939, was Hous-ton’s most eclectic architect. He made his career designing houses in a variety of architectural styles for the city’s elite. His houses were among the first in Houston to accommodate air-conditioning. While working for Staub, on a commission from the Humble Oil and Refining Company, Barthelme designed the company’s prototype super service station—an attempt to lure customers by making gas stations look dynamic and progressive.

Barthelme organized his own practice in Houston in 1940. “I told [Staub] I just didn’t like the fact that he didn’t change anything,“ Barthelme said. “I didn’t mind his traditionalism, but I thought he should improve on it, use it as a taking-off place. I just can’t understand why you take something and slavishly copy it.” That year, Barthelme won eighth place in a national competition sponsored by Architectural Forum magazine for a house, “the qualifications of which,“ according to contest rules, “should be the provision of a livable area so enclosed and organized by the materials used as to relate the elements of the building to one another, to the building as a whole, and to the land.” Barthelme’s non doctrinaire design, emphasizing spaciousness and light, was a personal exploration of modern materials and environmental sensitivity. He had now fully clothed himself in the modern.

In 1939, when Don was eight years old, his father conceived a house for the family in the newly platted West Oaks subdivision off Post Oak Road in what was then the extreme suburban fringe of Houston, well beyond the city limits. Completed in 1941, at 11 North Wynden Drive, the Barthelme house was unlike any the city had ever seen. A low-lying, dark-colored, flat-roofed rectangle with irregular projecting volumes and open interior spaces, it was “wonderful to live in but strange to see on the Texas prairie,“ Don said. “On Sundays people used to park their cars out on the street and stare. We had a routine, the family, on Sundays. We used to get up from Sunday dinner, if enough cars had parked, and run out in front of the house in a sort of chorus line, doing high kicks.”

His youngest brother, Steve, recalls, “The furniture...wasn’t like other people’s furniture. It was architect furniture, a lot of swoopy Scandinavian stuff”—Alvar Aalto and Eero Saarinen—”with large side helpings of Eames, the kind of furniture that pretty much stands up to announce, in a deep, rich chrome or molded-plywood voice, ‘Hi. I’m the chair.’ “

Before getting the go-ahead on his house, Barthelme had to wheedle the builder and the bank’s loan officer. Among other things, they were concerned about the master bedroom’s door. There wasn’t one. There was a screen behind the wall, say Rick and Steve, for “those non-architectural moments.”

One of the interior walls was brick. The others were made of redwood. A circular stairway led to a boxy room, which first served as Barthelme’s studio but then became Don’s bedroom as more children were born. Peter had arrived in 1939. Then Frederick was born in 1943, and Steven in 1947. “The atmosphere of the house was peculiar,“ Don said. There were “very large architectural books around and the considerations were: What was Mies doing, what was Aalto doing, what was Neutra up to, what about Wright? My father’s concerns, in other words, were to say the least somewhat different from those of the other people we knew.” In addition, he said, his mother had a wicked wit, which kept the kids hopping. She was their own “Lady of Texas,“ a playful but formidable figure.

Perhaps this hothouse ambience accounts in part for the kids’ later achievements. Joan became the first woman named corporate vice president in the male-dominated Pennzoil Company; Peter, a successful advertising man, published a series of sophisticated mystery novels; Rick and Steve, English professors at the University of Southern Mississippi, pursue literary fiction, both with great success. The “sheer literary talent and output of the Barthelme family has never, I think, been sufficiently recognized,“ wrote the literary critic Don Graham. “Perhaps only the James family—Henry, William, Henry senior—surpasses them in this regard.”

Barthelme was never happy with the house. He changed it constantly, taking saws to the furniture, rearranging the space, covering the floors—first with tatami mats, then tiles, then different tiles, then rugs. The kids came to see their house—”a cigar box with a cracker box on top,“ they said—as a perpetual work in progress, always subject to revision. The old man had “an ever-ready work force” in his children, Steve recalls. “He was prone to handing each of us a hammer and saying, ‘Tear out that wall there.’ “

Along one side of the house, bamboo served as a privacy shield. Its roots kept sneaking into the plumbing, requiring frequent repair. At one point, Barthelme covered the exterior wood with copper, believing that the copper, when coated with an acid compound, would discolor attractively. It simply turned brown, leaving him dissatisfied, though his kids liked the warps and ripples in it, the feel of the wood’s runnels underneath, and the soft light variations caused by reflections from swelling Gulf Coast clouds.

With its sharp corners and adjustable pathways, the house could be tricky terrain for a normally active child. Don had a further complication, which he discussed with J. D. O’Hara in their preparatory conversations for the Paris Review interview:

There was one thing that...affect[ed] my childhood, which is that I was subject to fits. I don’t quite want to say that it was petit mal. It was some sort of fits I had as a child, between eight and twelve or six and twelve, and I used to black out and fall, and it seems to have affected me. My family took me to a doctor to have me inspected by a neurologist who was then thought to be the best there was, and I had to take medication and so on. But it’s something that comes on you very suddenly, and you fall down and you go away, black out, and you come to...and this was really the main thing I remember about that period, the first dozen years, is that I was subject to this. And then, quite mysteriously, it stopped.

O’Hara asked him if the spells were “impressive for Dostoyevskian reasons.” Don replied, “No, it’s the loss of control. I mean, when you fall down without any warning, black out, it teaches you something. It had nothing to do with ecstasy, I’ll tell you, it had to do with somebody or something that could take away your consciousness at its volition rather than yours.”

He concluded, “Since it went away and has never come back, I think it probably manifests itself now only in dreams. Certainly dream correlations to this kind of feeling have endured into [my] mature life.”

Don deleted this exchange from the interview and never again spoke publicly of his “fits.” In the 1970s, he told a friend, Karen Kennerly, that his first memory of childhood was of having a seizure. His narrator in “See the Moon?” (1966) speaks of being “moonstruck,“ a word once used as a euphemism for epilepsy, and in his third novel, Paradise (1986), the main character, Simon, responds to his doctor’s question, “Ever been subject to epilepsy?” by saying, “I had seizures when I was a child. They stopped. I think it was petit mal.”

If Don’s memory of taking medications is correct, it’s likely that he was among the first children in this country to be given the anticonvulsant phenytoin, more commonly known as Dilantin, which came into widespread use in 1938. As an adult, he frequently spoke of being “nervous in the world,“ a lingering effect, perhaps, of the “fits.” In any case, the abrupt blackouts sometimes made his father’s house, ever-changing in the elder Barthelme’s search for perfection, a challenge to negotiate.

“Modernist architecture was a crusade, a religion, and the faithful couldn’t just go out and buy a rug like other folks,“ Steve says. Once, Barthelme decided he had to design a rug, which meant the family had to make one. “It took a month or so. About twelve feet by fifteen, assembled from three carpets, cut into long strips. It was a nice-looking thing once we finally got it finished and down, at one end of the big open living area, lying over the ghosts of those ornery tatami mats...which had the annoying habit of continually getting torn or disarranged.”

For better or worse, Barthelme’s “crusade” kept the family in a perpetual state of excitement. On the back porch, he kept his handsaws and rasps, his coffee cans full of nails. When Barthelme senior’s father died in the early 1950s, the lumberman’s tools came to live there, too. It was a “magical” part of the house, Steve says.

For Don and his siblings, the principles, methods, and means of architecture, as embodied in the house in which they came of age, gave life a mythic dimension. Their father taught them that all activity—sitting in a chair, eating dinner, hammering a nail, crawling into bed—bristled with artistic content. He taught them that nothing is set in stone, not even stone. And he taught them the power of an aggressive personality—”a designer is responsible for what he can do to people,“ he used to say. He convinced them that “everything good ever done was done by people who followed their own ideas.” He told them, “Walk alone, if necessary. Don’t walk the beaten path.”

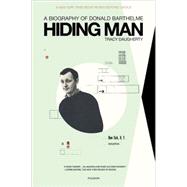

Excerpted from Hiding man by Tracy Daugherty.Copyright © 2009 by Tracy Daugherty.Published in February 2009 by St. Martin’s Press.

All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproduction is strictly prohibited. Permission to reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the Publisher.