What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

I was in high school when I readThe Bell Jarand thought it was about a lucky girl who wins a contest and gets to go to Europe. But what about Sylvia Plath's trying to drown herself? After she strings herself up and before she swallows pills? To tell you the truth, I don't think I looked at that part.

To tell you the truth, I must have skipped a lot of parts in that book, maybe even the whole thing, because, let's see, for starters, it takes place in New York.

Nevertheless: Sylvia Plath finally did get to go to Europe. She studied at Cambridge University in England, and years after I read her book -- or rather, some of her book -- so did I. While I was there, a collection of Plath's letters to her mother was published, which my mother read and wrote to me about. "Why can't you write letters to me like that?" she asked. "They're so warm and loving."

When I finally read the letters, long after I'd left Cambridge, I discovered that my mother was right. Sylvia Plath's letterswerewarm and loving. "Your mother is always right," my grandmother once told me, "although I have never liked the yellow table in her center hall." My grandmother also told me that she -- my grandmother -- believes everyone has a determined number of footsteps to use up in a lifetime, and, therefore, it is foolhardy to exercise since you will only exhaust your quota sooner and die.

Let me give you the gist of a typical Plath letter: "My dearest of Mothers, I met the most marvelous man at the Trinity May Ball, where I wore an ice blue gown that was simply divine. Tomorrow, tea with the Queen! I love you!"

I, too, had met a pretty marvelous man in England, though none of my letters home mentioned him. Let me give you the gist of one of those letters: "It's so cold here. And if you like the weather, you'llLOVEthe food. Do you remember what I'm supposed to be writing my thesis about? I have to hand a chapter in, but I can't remember what my topic is. I think I wrote the title in a postcard I wrote to you a couple of months ago. The bursar's office says they never received your check."

Sylvia Plath and I had one thing in common besides our outfits for socializing with the Queen -- mine being a never-worn, never-to-be-worn drab long skirt; and hers, well, to be honest, I can't actually say if she had an ice blue gown or ever met the Queen. As I told you, I was giving you the gist. In any case, Sylvia and I were alike in that both of us had a habit of shielding our mothers, and in my case, my father, too, from what was really going on in our respective lives. You know, of course, about Sylvia's despair and the conclusive oven thing. Even her mother knows now. But I don't think you know very much about me.

An only child, I was born in the suburbs of Philadelphia, a town called Abington. My ancestors were -- no, don't worry. I won't tell youeverything.I'll start when he knocked on my door.

The marvelous man was wearing a rugby shirt and jeans and sneakers and he looked boyish, I thought, for someone from another generation.

"You don't look twenty-eight," I said. I was twenty-one.

"You can count the rings," he said.

"You're married?" I said. He laughed.

"I meant tree rings," he said. "It was a joke about dendrochronology."

"Oh," I said. "I never get dendrochronological jokes."

He told me that he'd arrived from New York that morning, that he was going to be a teaching fellow in philosophy, that he'd recently been at Princeton, where he studied with someone famous I pretended to have heard of, that he'd taken a year off to join VISTA and eradicate poverty in Scarsdale (did I really hear him say Scarsdale?), and that a friend of mine had suggested he look me up -- he'd dated one of her roommates, who'd run off to an ashram in India after he broke up with her. She still wrote to him, though the motif, he said, was mainly gastrointestinal.

Those were the days when a person with a knapsack might knock on your door, say he was a friend of a friend of a cousin of an ex-girlfriend of a guy he had hiked with in Australia, and you then invited this person to sleep on your sofa and eat your food for as long as he felt like it. It was well within your guest's rights to take or break one of your cherished possessions, and unacceptable for you to care because that would be materialistic. Hitchhiking through Europe a year or so before, I had pulled that stunt in Amsterdam and ended up living for a week with someone who'd been a medical student for the last twelve years, during which time he'd saved the rind of every tangerine he'd eaten. Thousands of dried rinds, each a perfect half sphere, were stacked throughout the apartment. Toward the end of my stay, the rinds nearly burned to a crisp when I stood too close to the fireplace and my cheap pants burst into flame.

But Eugene Obello was only wondering if I'd like to go for a walk with him. Right now. Those were also the days before date books and plans and pretending you had something else to do in order to look popular. So I said yes.

While Eugene was in the bathroom, I took one of my smart-looking social theory books from my bookshelf and positioned it in a conspicuous spot. How far I had come from Abington High. "Remember Abington," the principal used to announce every morning over the PA. "First in the alphabet, first in achievement, and first in attitude!" We might have been first in the alphabet, but the other two...iffy.

And look at me now: Cambridge University! Abington was a large bland redbrick public high school built in the 1950s. This place was a dominion of majesty established in the thirteenth century by King Henry III. "I'm living like royalty," I wrote to my parents when I arrived. "Could you please send me my down quilt?"

Grungy-looking students hung out all day in the college bar, smoking hand-rolled cigarettes and drinking ale. Another clique modeled itself on the Bloomsbury group -- someone dressed and talked like Virginia Woolf, another like Clive Bell, another like Duncan Grant, and so on. There were some actual descendants of the Bloomsbury group at the college, but the look-alikes would have nothing to do with them, regarding them as poseurs. Even the student council was something to write home about: they issued a statement coming out against political, economic, and legal discrimination, which they happened to "deplore."

On the other hand, the school was still mostly made up of upper-class males, the first females having been accepted only a few years earlier. Some of the upper-class males belonged to a society whose sole function, so far as I could make out, was to break into the room of a first-year student, interfere with it, and leave a check for damages done. Then they peed in the fountain -- the one topped by a statue of Henry VI with the symbolic figures of Learning and Religion seated below.

So: the splendid architecture, the adorable boys' choir, the fields of daffodils...you get it. "They even have grazing cows on the lawns. How inspirational!" I wrote to my parents. "And I heard that only the students in MY college are allowed to shoot and eat the swans that swim on the Cam." In a P.S., I added, "INEEDmoney to go to Wales. Maybe you could sell my charm bracelet -- the one you gave me for my Sweet Sixteen? It's just a worldly object. Also, could you send me some hangers?"

That entire first year, gosh, I was happy. I was a foreigner! I'd never been to Europe and now here I was, in a country where everyone sounded like Winston Churchill or Mary Poppins; where all the women had flawless skin and all the men looked as if they'd been wandering around in the Underground since World War II, never having seen the light of day or another change of clothes. Every aspect of life in England seemed a notch from normal. Which made even the mundane exotic and exhilarating. I swear if I had been mugged on a greensward, this, too, would have been utterly delightful because he wouldn't have been just any mugger; he would have been a mugger with an accent.

You know what else is nice about being a foreigner? Whatever you do takes place in a capsule that need not be discovered and opened by someone back home. Nothing really counts -- it was the life that falls in the forest. That's how I looked at it. I felt free to...oh, I don't know.

Eugene returned to my bedroom. He'd been in the bathroom. "If it's not too rude to ask," he said, "bearing in mind I met you only a few minutes ago, and I hope I'm not entering some kind of kinky area here, or maybe I do" -- Eugene smiled, I didn't -- "but what are all those buckets and funnels doing in your bathtub?" I dropped my lip gloss into a drawer so he wouldn't catch me trying to look good while he'd been out of the room. Makeup seemed like cheating to me, then; but boy, oh boy, it doesn't now.

"I make ginger beer," I said.

Eugene took off his jacket and put it on my bed. "I lay a wager you didn't know that you can simulate ginger ale by combining Sprite with a splash of Coca-Cola," he said.

I picked up Eugene's jacket, looked around, considered what to do with it, put it back on the bed. "Really?" I said. Eugene stared at me while I thought hard what to say. "Sprite seems tough to make," was what I came up with.

"I'm not particularly fond of ginger beer," he said.

"Oh, I hate it," I said, wanting him to think we had an opinion in common. Incidentally, it was true. "But it's easy to make."

Why was a PhD-track graduate student who hated ginger beer involved with moonshine? Because my next-door neighbor, Obax Geeddi Abtidoon, a rich and beautiful Somalian who wanted to be a chef but was getting her degree in polar studies when she wasn't cooking curry and making sliced carrot salad for everyone on the floor, had given me the ginger beer starter and how could I be so rude as to throw it out?

Eugene sat on the only chair. His way of sitting there was so relaxed it put me on edge. Plus, this left the bed as the only place to sit, which seemed too friendly, but I perched myself on the edge anyway and tried to look nonchalant.

I know I said that the buildings at Cambridge were magnificent, but my dorm, built in the sixties out of concrete, was the exception. When I was happy, I found the room sterile and claustrophobia-inducing and depressing; when I was unhappy, I found the room sterile and claustrophobia-inducing and consoling. It was decorated, if that is the word, in basic dormitory furniture but with a touch of a color that could only be called veal -- veal curtains, veal bedspread, and a veal and gray shag rug. Instead of wallpaper, the walls were covered with grainy veal linoleum -- linoleum was definitely a theme in this building. A mechanical alarm clock sitting on a bookshelf was wrapped in a towel because someone had told me that fluorescence caused multiple myeloma. On the floor cartons of books lay, which I had insisted my parents ship to me because I believed I couldn't live without being surrounded by literature. I shipped them home every summer when I returned to Philadelphia and they came back with me every fall. I don't think I ever opened one, but this was a phase of my life when I wrote things in letters to my parents such as "I'm reading a lot of epistemology because I never had the chance in college," and, "Saw The Birthday Party last night in London. I could write like Pinter but when would I get around to it with this damn thesis around my neck?"

My room overlooked a courtyard in which there was a small man-made pond stocked with goldfish. After a potted gardenia I had placed on my windowsill fell into the pond, it seemed by volition, I went around saying that flowers committed suicide when they were near me. From my window, I could see my friend Libby's room, on the same floor. She and I constantly wrote notes, slipping them underneath one another's door. Libby was an undergraduate studying Anglo-Saxon, Norse, and Celtic, so her notes were, as she said, "strewn with rune." In a letter home, I compared Libby's wit with that of P. G. Wodehouse, though I had never read a single book of his.

"LetNrepresent the set of natural numbers," Eugene said.

"If it's up to me," I said,"Ncan be anything it wants."

"Very good," Eugene said. "Now let's put forth the proposition that there cannot be a set of all sets. And yet it seems also true that any group of items can be collected into a set, right?"

I nodded. It couldn't be possible -- could it? -- that upper-echelon philosophers were doing the same math that Miss Kilroy taught us in third grade?

I'd asked Eugene to explain what he was working on, a little bit because I wanted to know but mostly because I wanted to divert him long enough for me to walk over to the window and discreetly arrange the curtains so they obscured the sealed bottle of milk that had been sitting on my sill for about three months. I didn't know much about much, but something told me that putrefying milk was not the way to put one over on a suitor. I must have intuitively known even then, though, that if you ask a certain type of guy about himself, it's as good as winding a wind-up toy. For a given amount of time, said guy is in motion and requires only minimal attention from you. In this way, men are easier than plants.

"You really want to hear this?" he said.

"Yes!" I said.

The bottle, by the way, was an experiment, albeit one without a hypothesis. My research partner, Libby, and I were simply curious to see what would happen to very, very, very old milk. So far, blue and green had happened.

Let's now ignore Eugene while he describes what he's working on, throwing around some Greek symbols in the process. Meanwhile, I'll tell you what I was working on. Eugene had not asked, so it hadn't come up in our conversation.

Nothing.

In April, the month I met Eugene, my thesis topic, an ever-changing thing, had something to do with comparing the Jewish struggle against Fascism in the 1930s in Britain with the West Indian struggle against racism and the National Front today. The problem with that, it turned out, was they had almost nothing in common. My original topic had been "The Effects of the Changing Role of Women in a Yorkshire Fishing Village Upon Family and Social Structure." However, after I'd spent several weeks in an actual Yorkshire fishing village, interviewing dozens of people, it became clear that because of their accent I had no idea what anyone was saying. Transcripts of the hundred or so hours of tapes reveal that I frequently asked my subjects questions they'd just answered. And they were so polite. They answered again.

Whatever the topic, I was not working on it. Instead, I spent my time...come to think of it, I had turned into one of those people of whom I think, What do theydoall day?

Let's see. Leafing through brochures of Mediterranean islands to which I would never travel took time, as did my daily swim in the public pool across town. Then there were the excursions to the nearest department store to try on cashmere sweaters; to the open-air market to buy a mere satsuma orange. I taught myself to ride a bicycle without using hands and tried to teach myself German from a book, mastering only the phrase for "You are a fried egg" before I quit. I went to the Black Kettle across the street, where my work-shy friends and I lingered over cups of coffee for the sole purpose of eavesdropping on the inane conversations of tourists. (Man, pointing to the steps to the second floor of the restaurant; to waiter: "Do these stairs go up?") I made frequent visits to the stationery store to buy everything in sight. "Can you believe it?!" I wrote my parents. "This country has no double yellow adhesive labels! Please send some."

That's what I did all day, and curiously, nobody in a position of authority much cared. Two months had passed since I'd seen my adviser, Geoffrey Guppy, a genial man in his sixties, known for his work in the tribal politics of Guinea-Bissau and also in the sociology of what transpires during the first minute of conversation in different cultures. We'd met to discuss a chapter I'd written entitled "How Successful is T. S. Kuhn in Avoiding Problems of Relativism in His Discussion of Paradigms in Natural Sciences," for a thesis whose topic I can't conjure up today or perhaps even then. But I do remember his critique: "I looked up the word 'redeive,' " he had said, "and couldn't find it in the dictionary."

"It was a typo," I had said. "I meant 'receive.' "

"Jolly good. Carry on. Now. When you write 'in 1934,' do you mean 'in theyear1934'?"

There is nothing else in the English language that "in 1934" could possibly mean, but I kept that to myself. A week later, Geoffrey Guppy departed for Guinea-Bissau to do research and I was given a stand-in, Sean Shanahan, a scholar of revolution, who liked sherry and gossip. He believed that students were adults and should be treated as such, which meant he had affairs with some of them, though not with me. It also meant that he never broached the subject of my thesis. Geoffrey Guppy never returned to Cambridge, so don't worry about keeping track of his name. Sean Shanahan remained my temporary adviser forever. He will prove to be of only minor significance in this story. If you forget his name, I'll remind you the next time it comes up.

If a teacher believes that a certain undergraduate is not sharp enough to cut it in academia, is it the teacher's responsibility to dissuade said student from continuing his or her education, thereby saving the student money and time, or should the teacher respect the student's autonomy and simply hope that he or she will figure it out eventually?

Eugene and I began discussing this issue when he mentioned that a student of his from Princeton had recently asked for advice about applying to graduate schools. Eugene considered the student mediocre.

"You told him he was stupid?!" I said.

"I used a different word," Eugene said. " 'Obtuse.' "

"And what did he say?" I said.

"He said thank you," Eugene said. "He must have been thinking of 'astute.' "

Eugene and I were still in my room, though we hadn't been there as long as you probably think, maybe a half hour. We were having instant coffee, which I found delicious because it was Dutch. It didn't bother me that the coffee contained specks of crud -- all the more bohemian. I later realized I'd been drinking metal fragments from the electric kettle. I am including this detail in case I get a mysterious disease and the doctors need help with the diagnosis.

"You said he had a B-plus average at Princeton," I said. "How obtuse could he be?" Was there a way, I strained to think, to work in the fact without seeming to brag that I, too, had a commendable college grade point average?

"To make a career in philosophy you have to be brilliant," said the person who was making his career in philosophy.

"He could be a late bloomer. You never know," said the person who was beginning to fear she was an overachiever mistaken for an underachiever.

"Believe me," he said, stirring his coffee, "you can tell everything from day one."

"Isn't that playing God?" I said, thinking the phrase was sophisticated. I was also thinking that I should probably tell Eugene, still stirring away, that those were specks of crud, not lumps of coffee, in his coffee.

"I don't believe in God," he said. "And if Iwerea believer, I certainly wouldn't believe in deism." Deism? What did deism have to do with it? I was out of my league. "Maybe French deism, but certainly not the deism of Holingbroke or Locke," Eugene said. Does that clarify anything for you? Because it didn't for me. Then again, as I said, I was out of my league.

"Well, it's still cruel," I said.

"Honesty, in the long run, is always kindest," Eugene said. He set his mug on the bed table and was done with it.

Our conversation was rife with ironies and I missed them all. One always does when everything is going well. "Then again," Eugene said, "you know, of course, what Nietzsche said about lying?" This is what I came to Cambridge for, I thought: stimulating intellectual conversation.

There are two ways to deal with an awkward pause. You can fill the void by babbling or you can suppose it's the other person's fault and wait it out. Hold on. There's a third approach. You can exploit the opportunity and make a sexual advance. I was afraid that Eugene would go for that, so I preemptively asked him, "Are there any rivers in Nebraska?" Eugene had grown up in Missouri.

"There's the Niobrara River, obviously," said Eugene, "and the Platte River and the Missouri River and the Republican River and the Loup River, both the North Loup and the South Loup." Eugene picked up his knapsack. He had that gearing-up-to-say-good-bye look.

"Yeah, yeah," I said, "I mean besides those? Tributaries." Eugene got up. "Or maybe byways," I said. That might have been the end of him for me. I had an awful suspicion that a byway was a minor road, having nothing to do with a river. But the door opened.

"You're here!" said Libby, meaning me, not Eugene. Standing next to her was a guy I'd never seen before and, instantly, I understood what had happened. When I had adjusted my curtains to hide the bottle of milk, I'd inadvertently arranged them in a way that sent Libby, who -- remember? -- could see my window from hers, a message that I was leaving and she could use my room for entertaining. Our elaborate semaphore system, based on which lights were on and how the curtains were drawn, included code for "Trying to work. Please disturb"; "Wake me up by noon"; "I'm drunk. Do you have aspirin? What day is it?"; and "I just thought of another reason I despise Tamar Grubley." Libby's room, by the way, was too messy for trysts.

I know you're thinking: Ewwww, lending out your room forthat?But we had illicit keys to the closet where housekeeping kept fresh linen. And lest you think I got the short end of the deal, I should mention that Libby allowed me the use of her computer (mine had crashed without warning) and whatever else was in her room while she was at lectures, the library, and engaged in other studious activities. Libby was able to play and work whereas I couldn't do either. But my room was neat. And I had to get out of it immediately.

I grabbed Eugene's arm. "This is Eugene," I said with haste, "and he and I are going for a walk."

We walked along the gravel path that squared the Front Court of the college, a large turf of grass that had been perfectly tended for well over five hundred years. Then we cut the corner and walked on the grass, though signs in many languages clearly stated, KEEP OFF THE GRASS UNLESS YOU ARE A FELLOW OF THE COLLEGE! It doesn't sound thrilling, but believe me, it was.

We continued down the path, past a grand building that looked like a little nation's capitol. When we made our way to the Back Lawn, I was glad to be noticed by a show-off who had gone to college with me in the United States and was using every last pence of her National Science Foundation Fellowship to buy upmarket wine. Eugene was terrific-looking and I knew she'd be jealous.

(At this point, I think it behooves me to tell you what Eugene looked like. But description is the part I skip when I read a book, so let's just leave it that he was terrific-looking, okay? And kind of, well, nondescript. If you really care what color his hair was or whether his eyes were shaped like almonds or pistachios, write to me and I'll send you a picture.)

But here's the more important part: we were also noticed on the Back Lawn by Oliver Qas (pronounced like the French word for "what"). Oliver Qas was a theologian in his second year from Trinidad, who was maybe more terrific-looking than Eugene and with whom I'd almost had a fling when I arrived in Cambridge and who flourished a walking stick. I could count on Oliver saying hello in a flirty way and he did. "If it isn't the toast of two hemispheres," he said.

On the other hand, I was not glad to be noticed by Laurence Hesseltine, a rabbity-looking English third-year studying artificial intelligence, who'd been chosen by Stephen Hawking as one of the undergraduates whose job it was to push him around in his wheelchair and guess what he was saying. Laurence saw me and waved, bending his fingers as if he were waving to a baby. I started to wave back but in midgesture worried that this might encourage Laurence, who had never spoken to a girl, to speak to me, so I combed my fingers through my hair as if that had been my intention all along.

Eugene noticed none of these people. He was explaining the sorites paradox, also known as the heap paradox. "One grain of sand isn't a heap," he said. I kicked a stone. "And if you add one more grain of sand, it still isn't a heap, do you follow?"

Eugene and I caught up with the stone and I kicked it again.

"If you add a third grain of sand," Eugene said, "it still isn't a heap. And so forth ad infinitum. It seems, then, that there can be no such thing as a heap of sand. Yet, we know there is. Which is why it's called a paradox."

"The heap paradox," Eugene said, "was at the root of a lot of debates -- when is a fetus a living being, when is the budget too high, when do you pull your troops out of a war that seems a lost cause? Where do you draw the line?"

I did some more stone kicking. "Do you know the bookSeven Types of Ambiguity?"I said, referring to a book they had made me read in school. I had a vague hunch it was relevant to what Eugene was talking about. I needed Eugene to think that I was smart.

Eugene nodded. "William Empson," he said.

"Don't you think a better title would beSeven or Eight Types of Ambiguity?"I said. I needed Eugene to think I was clever, too. Eugene chuckled.

We had come to the Backs, the strip of land that was on the side of the Cam opposite to my dorm. The Cam, lined with willow trees, was closer to a creek than a river, but beautiful. Students and tourists glided by in punts. The lawns were covered with daffodils and those little purple flowers that I think are called crocuses. The sun was setting. I thought, This is what I'm supposed to think is romantic. Now Eugene kicked the stone.

We stood, facing each other. He fixed his eyes on me and I wondered what was next. How do two people move from talking to not talking to doing it? He raised his hand. Was he going to kiss me? Then he scratched his shoulder. I have to tell you the idea of what might happen made me anxious, which may explain why I was, as I will later demonstrate, the least experienced twenty-one-year-old, if you don't count Mormons, who, come to think of it, are probably married by twenty-one, so scratch that. At least, I thought, Eugene didn't look like a man. He looked my age, or even younger.

"Did any presidents come from Missouri?" I said.

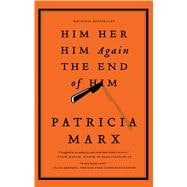

Copyright © 2007 by Patricia Marx

Excerpted from Him Her Him Again the End of Him by Patricia Marx

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.