| Preface | |

| The Man in Blue | p. x |

| An American Palindrome Sunday, Monday, and Charlie | p. 7 |

| The Old Roman Gardens | p. 12 |

| Deeyan and Allan | p. 17 |

| What More Can You Ask For? | p. 22 |

| Early Bob | p. 32 |

| Life in the Colonies | p. 40 |

| Bob: The Middle Years | p. 43 |

| Simoom in the Sahara | p. 47 |

| Diane and John | p. 53 |

| Jan, Meg, Ernie, and Mom | p. 59 |

| Miss McRae | p. 64 |

| The Final Act | p. 67 |

| Black History | p. 71 |

| The Collectors | p. 75 |

| Out of Africa | p. 81 |

| Feeding the Rat | p. 87 |

| The Buy | p. 92 |

| The Finer Sort | p. 98 |

| Flying Fur | p. 104 |

| Down the Rabbit Hole | p. 110 |

| The Grind | p. 118 |

| A Crack in the Mystical Vessel | p. 129 |

| Bob and Woogie | p. 134 |

| Deconstructing the Palindrome | p. 138 |

| New Bob The Kiss and the Curse | p. 145 |

| Paper Pajamas | p. 151 |

| Off the Couch and into the Frying Pan | p. 156 |

| Yes!!! Fantastic!!! And Fascinating !!! | p. 162 |

| Robert Miller | p. 168 |

| A Shark’s Lunch | p. 174 |

| Consummatum est | p. 185 |

| The Magic Cloud | p. 191 |

| Bob and Steve | p. 196 |

| Other Faces | p. 202 |

| Woogie’s Boxes | p. 207 |

| The Old, Weird Bob | p. 222 |

| The Bostocks of West Philadelphia | p. 231 |

| Deep Leo &nbs | |

| Table of Contents provided by Publisher. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Sunday, Monday, and Charlie

In 1831 a Yankee sea captain named Benjamin Morrell captured two cannibals in the South Pacific and brought them back to America. For the next few years he displayed them throughout the northeastern United States at places like New York City’s American Museum. He wrote a book about his adventures, and his wife, who accompanied him on the voyage, wrote her own account, which verified his. A third narrative, written by a crewman named Keeler, substantiated both the Morrells’ books.

The two savages, named Sunday and Monday in honor of the days on which they were captured, astonished American audiences. Captain Morrell wrote, “In the year 1830 they were . . . cannibals! In the year 1832 they are civilized intelligent men.” Morrell assured his readers that the two former cannibals would prove to be ideal ambassadors to their home islands, overflowing with breadfruit, coconut, and “many other valuables,” when a trading expedition returned there. Stockholders of the proposed commercial venture, he said, would have a monopoly on the abundant profits because, “I alone know where these islands are situated.”

As it turned out, Morrell’s book was ghostwritten by a hack friend of Edgar Allan Poe’s named Samuel Woodworth; Mrs. Morrell’s account was ghostwritten by another friend of Poe’s; and most of Keeler’s narrative was lifted verbatim from his captain’s book. All three of these texts, though based loosely on fact, were rife with exaggeration. Captain Morrell was simply trying to drum up interest in the remote Pacific and to promote himself as an expert navigator of those waters. He hoped to attract backers for a grand trading venture, or even for a government-sponsored expedition (to be led, of course, by himself). But the only person to make any real use of his ghostwritten saga was Edgar Allan Poe, who basedThe Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pymon it.

Morrell’s extravagant claims didn’t fool his fellow mariners. He became known as “the biggest liar in the Pacific,” and he died at sea without ever realizing his grandiose schemes. Sunday and Monday, his faux cannibals, were probably just domesticated Pacific Islanders or African American impersonators, posing as savages to astonish white American rubes. They were among the earliest examples of such, and although they are long forgotten, they bear on the story of Bob Langmuir and Diane Arbus.

Arbus started photographing at Hubert’s Museum, a freak show on West Forty-second Street, in the 1950s. At first she was more interested in the interiors of the nearby movie houses—her photos show half-lit faces and blurred bodies rising like dreams out of those huge, dimmed bowls—but Hubert’s bizarre shabbiness ultimately proved a more fertile environment in which to pursue the images she was seeking. She recalled descending, “somewhat like Orpheus or Alice or Virgil, into the cellar, which was where Hubert’s Museum was.” That it occupied its own underworld only enhanced it.

Charlie Lucas, a black man from Chicago who worked as the “inside talker” and manager at Hubert’s Museum, was Arbus’s friend and collaborator during the years she photographed there. He was her link to the freaks and performance artists and, in a larger sense, to the culture and traditions of the freak show. He made the introductions for Arbus and in some cases set up photographic shoots with the performers.

He’d been working circuses and sideshows in the U.S. and Canada since 1924, but he got his big break at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933. This event, commemorating the one hundredth anniversary of Chicago’s incorporation as a city, was billed as the “Century of Progress.” Splendid deco artifacts and architecture adorned the midway, along with a great deal of sideshow hokum, such as the Midget Village or the Infant Incubator Building, where crowds could gawk at real, live premature babies, attended by flocks of nurses.

Charlie Lucas presided at the Darkest Africa exhibit as, in his words, “African Chief of the Duck Bill Women.” The core of his “tribe” was composed of fourteen authentic Ashantis who’d migrated to Manhattan and been hired there, where the show had been conceived. The rest of the “natives” were recruited from Chicago pool halls, and the lot of them were decked out in leopard-skin sarongs and zebra-hide shields furnished by Brooks Costume Company, also of New York City. America was still in the grip of the Great Depression. There was no shortage of African American talent available for the impersonation of wild savages—an act that had lost none of its appeal since Morrell’s day. Produced by white sideshow promoters, and occasionally enlivened by a few authentic Africans, the African Village became a staple of pre–World War II sideshow entertainment.

At the Century of Progress, Charlie was billed as WooFoo, the Immune Man. He had a bone supposedly clamped through his nose, dressed in ostrich feathers, and talked gibberish. Aside from his chiefly duties, he swallowed fire and climbed ladders of saw blades. In the tradition of blacks performing as savages, there hadn’t been a great deal of progress since Sunday and Monday first took the stage a century before.

Copyright © 2008 by Gregory Gibson

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be submitted online at www.harcourt.com/contact or mailed to the following address: Permissions Department, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, Florida 32887-6777.

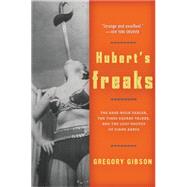

Excerpted from Hubert's Freaks: The Rare-Book Dealer, the Times Square Talker, and the Lost Photos of Diane Arbus by Gregory Gibson

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.