| Preface | p. 1 |

| Pausing in Continuity | |

| I Have Landed | p. 13 |

| Disciplinary Connections: Scientific Slouching Across a Misconceived Divide | |

| No Science Without Fancy, No Art Without Facts: The Lepidoptery of Vladimir Nabokov | p. 29 |

| Jim Bowie's Letter and Bill Buckner's Legs | p. 54 |

| The True Embodiment of Everything That's Excellent | p. 71 |

| Art Meets Science in The Heart of the Andes: Church Paints, Humboldt Dies, Darwin Writes, and Nature Blinks in the Fateful Year of 1859 | p. 90 |

| Darwinian Prequels and Fallout | |

| The Darwinian Gentleman at Marx's Funeral: Resolving Evolution's Oddest Coupling | p. 113 |

| The Pre-Adamite in a Nutshell | p. 130 |

| Freud's Evolutionary Fantasy | p. 147 |

| Essays in the Paleontology of Ideas | |

| The Jew and the Jewstone | p. 161 |

| When Fossils Were Young | p. 175 |

| Syphilis and the Shepherd of Atlantis | p. 192 |

| Casting the Die: Six Evolutionary Epitomes | |

| Defending Evolution | |

| Darwin and the Munchkins of Kansas | p. 213 |

| Darwin's More Stately Mansion | p. 216 |

| A Darwin for All Reasons | p. 219 |

| Evolution and Human Nature | |

| When Less Is Truly More | p. 225 |

| Darwin's Cultural Degree | p. 229 |

| The Without and Within of Smart Mice | p. 233 |

| The Meaning and Drawing of Evolution | |

| Defining and Beginning | |

| What Does the Dreaded "E" Word Mean Anyway? | p. 241 |

| The First Day of the Rest of Our Life | p. 257 |

| The Narthex of San Marco and the Pangenetic Paradigm | p. 271 |

| Parsing and Proceeding | |

| Linnaeus's Luck? | p. 287 |

| Abscheulich! (Atrocious) | p. 305 |

| Tales of a Feathered Tail | p. 321 |

| Natural Worth | |

| An Evolutionary Perspective on the Concept of Native Plants | p. 335 |

| Age-Old Fallacies of Thinking and Stinking | p. 347 |

| The Geometer of Race | p. 356 |

| The Great Physiologist of Heidelberg | p. 367 |

| Triumph and Tragedy on the Exact Centennial of I Have Landed, September 11, 2001 | |

| Introductory Statement | p. 387 |

| The Good People of Halifax | p. 389 |

| Apple Brown Betty | p. 393 |

| The Woolworth Building | p. 396 |

| September 11, '01 | p. 399 |

| Illustration Credits | p. 402 |

| Index | p. 404 |

| Table of Contents provided by Ingram. All Rights Reserved. |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

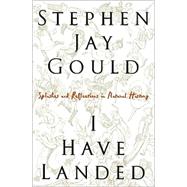

Excerpted from I Have Landed: The End of a Beginning in Natural History by Stephen Jay Gould

All rights reserved by the original copyright owners. Excerpts are provided for display purposes only and may not be reproduced, reprinted or distributed without the written permission of the publisher.