| Author's Note | 7 | (11) | |||

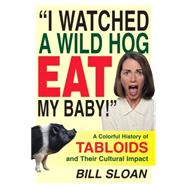

| Prologue. How Tabloids are Written: First the Headline, Then the Story | 11 | (6) | |||

|

17 | (12) | |||

|

29 | (14) | |||

|

43 | (12) | |||

|

55 | (12) | |||

|

67 | (12) | |||

|

79 | (16) | |||

|

95 | (14) | |||

|

109 | (14) | |||

|

123 | (12) | |||

|

135 | (12) | |||

|

147 | (18) | |||

|

165 | (14) | |||

|

179 | (12) | |||

|

191 | (16) | |||

|

207 | (10) | |||

|

217 | (16) | |||

| Appendix. Chronology of Tabloids | 233 | (6) | |||

| Selected Bibliography | 239 | (4) | |||

| Index | 243 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

SPICING UP THE NEWS

THE EVOLUTION OF SENSATIONALISM

Ever since the invention of movable type and the printing press five and a half centuries ago, people have been clamoring for "news," and for much of that time, journalists have been arguing among themselves about just what "news" is or isn't--and what it should or shouldn't be.

In the process, an endless conflict has developed between two divergent schools of thought within what we now call the journalistic profession. One school believes in covering the news with scrupulous dignity, weighty seriousness--and a great many dull stories. The other school has often thumbed its nose at convention and civility, and catered shamelessly to baser human instincts. Journalists of this persuasion are seldom averse to tweaking the facts a bit or leaving out a few bothersome details to "liven up" the news and get their readers more emotionally involved.

The New York Times , with its lofty credo of "All the News That's Fit to Print" and its insistence on referring to every serial rape-murderer as "Mr." amply typifies the philosophy at one end of the spectrum. Such flagrant fabrications as National News Extra and, more recently, Weekly World News represent the opposite end. The rest of today's print media fall somewhere in between.

The common folk of the Western world, however, have never had much difficulty deciding what brand of news they prefer. Given the chance, they've invariably chosen shipwrecks over shipping notices, crime and carnage over commodity futures, and whorehouse raids over wholesale price indexes. For them, the more shocking the news, the better.

Some intuitive publishers, editors, reporters, and writers have grasped all this since printing began. For the better part of two centuries, they've learned to structure their papers around a couple of basic, undeniable truths about the news business: (1) In its most socially powerful and financially successful form, journalism is at least as much about playing on the reader's emotions as about disseminating information. (2) The best way to sell lots of papers is by entertaining the masses, not by enlightening them.

These are the same precepts that those News Extra staffers in Chicago came to understand so well--and practice so adeptly--in the mid-1970s. But they were far from the first to discover them. No single factor has played a bigger role in the way today's news media gather and display the news than the public's timeless desire to be horrified, outraged, amazed, scandalized, amused, infuriated, and titillated (not necessarily in that order).

This lust for sensation predates by many centuries the appearance of the first newspaper in Germany in 1609. It can be found in the bloodcurdling ballads sung by wandering balladeers in the sixteenth century, the crowds that flocked to public beheadings in the Middle Ages, the gruesome "games" of ancient Rome, and all the way back to prehistoric times.

Clearly, then, sensationalism wasn't invented by the modern press, much less the architects of the supermarket tabloids. What the tabs did do, though, over the almost half century between the mid-1950s and the late 1990s, was add an irresistible new flavor to it--one so delectably irreverent and seductively spicy that a vast segment of the reading public became addicted to it.

Because of this addiction, neither school of American journalism will ever be the same again.

* * *

If today's print and electronic media suddenly reverted to presenting the news in as bland and boring a manner as it was presented in the early 1800s, most people would simply ignore it--just as they did then. It wasn't until the 1830s that the public was first introduced to sensational crime reports and bizarre "human-interest" articles, and ordinary citizens started buying and reading newspapers in significant numbers.

Benjamen Day's New York Sun and James Gordon Bennett's New York Herald were the first American dailies aimed less at upper-class businessmen and politicians than at an audience of semiliterate, urban working people. Up until that time, newspapers had generally been too expensive for most working-class readers, and circulation was largely confined to the wealthy.

The Sun and Herald gave birth to what became known as the Penny Press, because they were the nation's first papers to sell for one cent per copy, compared to six cents for most other papers of the period. If that sounds like a negligible difference, consider that in 1830, six cents was roughly half a day's pay for a common laborer. Translated into current economic terms, this is the equivalent of today's six-dollar-an-hour worker paying twenty-four dollars for a copy of his local paper--something that's not likely to happen today or any other time.

On this same scale, of course, an 1830 penny would amount to about four dollars now--still a high price--but the journalists who produced the "penny dreadfuls" gave the masses some thrills and chills for their money that couldn't be found anywhere else. Present-day readers would likely find those penny papers as dull as dirt, but at the time, they were the hottest things going. They introduced the term "sensationalism" to our vocabulary to describe their concept of presenting news, and it's been evolving ever since.

The low price and high-octane content of the Penny Press proved a dynamic combination. In just over a decade, U.S. daily newspaper circulation jumped from about 80,000 to over 300,000--not because the public was suddenly more literate or eager for edification but because of the same morbid curiosity and primitive instincts that draw people to fatal fires, grisly accidents, or carnival freak shows. The gruesome, the grotesque, the forbidden, the depraved--the unthinkable --have always had tremendous dark appeal, and devotees of the second school of journalism gradually realized how to capitalize on it.

In 1883, a half century after the advent of the Penny Press, Joseph Pulitzer took the next major step in the evolution of sensationalism when his New York World introduced "yellow journalism" to the nation. Essentially, it was the same fare offered earlier by Day and Bennett, except that it was now presented in a far more exciting, provocative, melodramatic way.

The World thrived on lurid accounts of murder and mayhem--the bloodier and more heinous the crime, the more space it commanded--and fleshed out its reports with vivid descriptions and crude but colorful dialogue. Consider, for example, a World story on the murder of a tenement dweller named Kate Sweeney. The writer first describes a young female courtroom witness as resembling "a hard, blighted peach," then quotes directly from her testimony:

"What was she [the victim] doing in the cellar?"

"How the -- should I know? Mabbee she went down there to git some peace."

"You're a liar," said another woman who had her front teeth knocked out and whose voice hissed viciously through the apertures.

Pulitzer himself described the World's style of reporting as "original, distinctive, dramatic, romantic, thrilling, unique, curious, quaint, humorous, odd [and] apt to be talked about." In essence, it was precisely the same formula that would sweep the supermarket tabloids to the apex of their popularity and profitability a century later.

But even more than Pulitzer, it was William Randolph Hearst who set a lasting standard for the supermarket tabs to follow. When Hearst moved east from California and bought the struggling New York Journal in 1895, he began pouring millions into it in a no-holds-barred campaign to overtake and surpass the World in circulation. In his obsessive pursuit of this goal, Hearst pushed sensationalism to new and hitherto unexplored heights--or depths, depending on one's perspective. As a by-product of this campaign, he managed to become the only American newspaper publisher ever to start a major war. He got more than a little help from Pulitzer, but when hostilities with Spain broke out in 1898, it was Hearst's Journal that inquired in a self-congratulating front-page headline, "How Do You Like Our War?"

Hearst also perfected the journalistic penchant for blowing one's own horn to a fine science. As adept as the supermarket tabs later became at this game, they never came close to matching his gift for self-praise. In a back-patting editorial on the first anniversary of his purchase of the Journal , he exulted:

What is the explanation of the Journal's amazing and wholly unmatched progress? ...

No other journal in the United States includes in its staff a tenth of the number of writers of reputation and talent. It is the Journal's policy to engage brains as well as to get the news, for the public is even more fond of entertainment than it is of information.

When George Arnold, a perceptive Hearst reporter, helped establish the identity of a decapitated murder victim whose head was missing--a revelation that led to the arrests of the man's former girlfriend and her new lover--a Journal headline trumpeted:

MURDER MYSTERY SOLVED BY THE JOURNAL

Hearst also capitalized on the perverse pleasure that the "common herd" finds when the wealthy, powerful, and famous get knocked off their pedestals and reduced to the same vulnerable, foolish, all-too-human state as the rest of us. Whether the focal point happens to be the stereotypical pompous rich man slipping on a banana peel or a president of the United States sexually disgracing himself before the world, the mass reaction is roughly the same: "Thinks he's better than the rest of us, huh? Well, by God, that'll show him!"

More than seven decades before Teddy Kennedy's misadventure at Chappaquiddick and Jackie Onassis's transformation from martyr's widow to fallen angel--courtesy of the supermarket tabs--Hearst was proving his aptitude at character assassination. He repeatedly assailed Presidents Grover Cleveland and William McKinley as gutless tools of the superrich and cowards who ignored Spanish atrocities in Cuba.

As Hearst and those who followed in his footsteps well knew, one of the keys to successful sensationalism is to accentuate the negative. To most people, no news may be good news, as the old saying goes, but for the sensationalist, just the opposite is tree--good news is no news. A positive stow may arouse emotions, but it has no shock value. On the other hand, it's easy to sensationalize negative stories, thanks to a shadowy side of human nature that invariably tends to suspect the worst about any person or situation. Confirming such suspicions is a major element of sensationalizing the news.

After Spain's defeat, for example, the Journal launched an all-out round of assaults on Secretary of War Russell Alger, whom it branded a heartless mass-murderer. A few of the headlines on Hearst-concocted stories vilifying Alger included these:

DYING HEROES SHIPPED TO HOSPITAL BY FREIGHT

FOOD ROTS ON TRANSPORTS WHILE SOLDIERS STARVE

STORY OF HORRORS HOURLY GROWS WORSE

Decades later, each of the major supermarket tabloids had an ongoing category of stories loosely styled "government waste/stupidity/corruption/ coverup" which they tried to fill in every issue. If a story already had substantial shock value, putting a negative spin on it got the reader even more emotionally involved. "Air Force Knows UFOs Exist" made a fairly arresting headline in itself, but adding the phrase "--And the Gov't Isn't Doing Anything About It!" made it even stronger.

The thought of space aliens watching us from the skies was terrifying to millions of Americans in the 1960s and 1970s, but the idea that the government was refusing to face the problem or concealing information about it was also infuriating to many people who instinctively despise and distrust those in power. Thus, one story could be milked for two basic negative emotions.

When a specific personality, rather than faceless "big government" in general, can be singled out for negative target practice, the effect on readers is often intensified. One of the Journal's more outrageous pieces of reportage, for example, concerned Teddy Roosevelt while he was police commissioner of New York City in the 1890s. In a stow based on reckless rumors, Hearst accused TR of planning to attend a stag party where Ashea "Little Egypt" Wabe, the notorious exotic dancer of the Chicago World's Fair, was to perform a totally nude belly dance. It was a charge the future president hotly denied, but as the supermarket tabs would prove repeatedly later, denials can sometimes be just as juicy as accusations.

"Hoist," as he was known among admiring New Yorkers, saved his "woist" for William McKinley, however. Between 1898 and 1901, Hearst aimed a withering, continuous barrage of negative fire at McKinley through the pages of the Journal . In editorial cartoons, he pictured presidential advisor Mark Hanna as the grossest imaginable monster, covered with dollar signs and leading McKinley around as a pygmy slave.

Hearst's attacks on McKinley were so unremittingly vicious, in fact, that when the president was mortally wounded by an assassin--who was erroneously reported to have a copy of the Journal in his pocket at the time of his arrest--Hearst feared the public would blame him directly.

"Things are going to be very bad," he muttered to one of his editors when he heard that McKinley had been shot.

In his first speech to Congress after assuming the presidency on McKinley's death, Teddy Roosevelt had some special harsh words for "the reckless utterances of those ... in the public press [who] appeal to the dark and evil spirits of malice and greed, envy and sullen hatred."

There was little doubt about the object of Roosevelt's scorn. But in addition to referring to Hearst's merciless assaults on McKinley, TR may also have been remembering that earlier Journal "scoop" about Teddy and "Little Egypt."

* * *

Along with politicians, Hearst also singled out show business celebrities and other famous figures for special attention, just as the national tabloids did later. One of Hearst's favorite ploys was to hire a well-known personality at an exorbitant fee to write or report on other famous people for the Journal . He engaged Mark Twain to cover the sixtieth anniversary of Queen Victoria's coronation. He assigned a former U.S. senator to cover the Corbett-Fitzsimmons heavyweight boxing match in Nevada. He sent celebrated artist Frederick Remington to Cuba to illustrate the massive conflict with the "barbaric Spanish ruffians" that Hearst had worked tirelessly to orchestrate and was now certain would soon begin.

After weeks of doing nothing in Havana, Remington wired Hearst:

Everything is quiet. There is no trouble here. There will be no war. I wish to return.

Hearst wired back confidently:

Please remain. You furnish the pictures and I'll furnish the war.

When the U.S. battleship Maine blew up in Havana harbor of causes that remain a mystery even today, more than a century later, Hearst and the Journal got "their war." They got it despite the fact that no legitimate evidence ever linked Spain or its military forces in Cuba to the blast, which most historians now believe was simply an accident. When war was declared, the Journal celebrated it with a thundering four-inch-tall headline proclaiming:

NOW TO AVENGE THE MAINE!

In the words of Hearst biographer W. A. Swanberg: "Hearst's coverage of the Maine disaster still stands as the orgasmic acme of ruthless, truthless newspaper jingoism"--and even that was probably an understatement.

Yet there could have been no better role model for the founders of the early national tabloids than Hearst at his most outrageous and creative. Hearst taught the American public to accept, enjoy, and even admire blatant, heavy-handed sensationalism. Without his example and influence, the modern tabloids might never have happened at all, much less achieved the level of success they enjoyed for more than forty years. More significantly, the "tabloidization" of today's mainstream media and the subtle changes that have taken place in "responsible journalism" over the past quarter century would have been virtually impossible.

Probably not even Hearst could have predicted that the New York Times would one day be quoting the National Enquirer as a primary source of exclusive information on the O. J. Simpson murder case.

And if the heyday of the tabloids now appears to be fading away, the most obvious reason is that they've simply been out-sensationalized by their more serious minded, more "respectable" counterparts.

* * *

The word "tabloid" entered the English language innocently enough and with none of the scurrilous connotations that later attached themselves to it. In their original context, tabloids were merely papers whose pages were half the size of traditional "broadsheets." It was an innovation that made the paper easier to handle by commuters on crowded trolleys and subways.

The first tabloids appeared in London in the 1890s, where the concept was pioneered by Alfred C. Harmsworth (later Lord Northcliffe), founder of Britain's venerable and still phenomenally successful Daily Mirror . By this time, the trend toward sensationalism had already been accelerating on both sides of the Atlantic for more than sixty years.

The first American tabloid of any consequence was the Daily Continent , established in New York in 1891 by Frank A. Munsey. It was no match, however, for the Pulitzer and Hearst giants and soon vanished amid the sound and fury of the circulation war between the Journal and the World .

In the heat of this battle, Hearst had the gall to condemn Pulitzer as "a journalist who made his money by pandering to the worst tastes of the prurient and horror-loving [and] by dealing in bogus news." If there was ever a case of the pot calling the kettle black, this was it. Pulitzer was a sensationalist, but he was also, in many respects, an idealist who crusaded endlessly for the public good.

The man for whom the Pulitzer Prize, the most prestigious award in journalism, is now named was far removed from the day-to-day editorial operation of his newspapers (he also owned the St. Louis Post-Dispatch ). He dictated the overall tone and sociopolitical posture of the World but, by and large, he let the professional editors and reporters who worked for him decide which stories to run and how to display them.

Hearst, on the other hand, was the epitome of the hands-on publisher. He undoubtedly had fewer scruples than Pulitzer, and his ethics were defined by whatever sold papers at the moment. But unlike his rival, he was always in the thick of the news-gathering operation, and his instincts for what working-class readers wanted were even sharper than Pulitzer's. He took a personal interest in every big developing piece of news, and he didn't care what it cost to get it. The Journal lost an estimated $8 million before it began to show a profit--so much that Pulitzer firmly expected it to go bankrupt any day. But thanks to Hearst's generous and fabulously wealthy mother, there was always plenty more money in reserve, at least during her lifetime.

Regardless of how he managed to do it, Hearst forever altered the style and course of America's media. Along with his disregard for truth and tradition, he pioneered such innovations as sports pages, comic sections, advice columns, and women's features. No figure in the history of newspapers was more despised by the industry's serious school and the national political establishment than Hearst. (One U.S. senator of the 1920s described Hearst's growing chain of papers as "the sewer system of American journalism.") But because of his influence, politicians from the White House on down feared his wrath.

Hearst's editor at the Journal , Arthur McEwen, was probably the first person to coin the term "gee-whiz emotion" to describe what the paper's writers were trying to evoke in their readers. Seventy-five years later, every staffer of every supermarket tabloid would be on constant lookout for these very same "gee-whiz" stories.

But neither Pulitzer nor Hearst was sold on the tabloid format, despite its demonstrated success in London. At Pulitzer's invitation, Harmsworth designed a tabloid version of the World , which was published on New Year's Day, 1901, and hailed as "the newspaper of the twentieth century." Circulation for the day jumped by more than 100,000 copies, but New York was generally unimpressed and, after that one issue, the World reverted to a broadsheet.

During World War I, Harmsworth met Capt. Joseph Medill Patterson, copublisher of the Chicago Tribune , who was on leave from the paper to serve in the U.S. Army. Harmsworth convinced Patterson that New York needed a tabloid daily of its own, and immediately after the war, Patterson and his partner at the Tribune , Col. Robert R. McCormick, took the Britisher's advice.

In June 1919, McCormick and Patterson published the first issue of the Illustrated Daily News , the first successful tabloid daily in North America, and this time New Yorkers ate it up. Predictably, journalism's serious school dismissed this half-sized upstart as a flash in the pan, but they were soon forced to change their tune. Within two years, the Daily News led all New York dailies in circulation with over 400,000. By 1924, it was selling 750,000 copies a day and claimed the nation's largest circulation. Before the end of the decade, the figure had hit an unheard-of 1.3 million at a time when sales of all other New York papers were standing still.

By the mid-1920s, Hearst had seen enough to jump belatedly onto the tabloid bandwagon. After changing the name of the Journal's morning edition to the American , he watched both its and the evening Journal's circulation turn stagnant. In 1924, he introduced New York to his own Americanized version of the Mirror , and set out to tear away at the Daily News's following in the same way that he'd undermined Pulitzer's World in the 1890s.

This time, though, he wasn't nearly as successful. Despite his best efforts, the Mirror's circulation stalled at 600,000 while sales and readership of the Daily News continued to climb.

Hearst promised at the time that the Mirror's aim would be "90 percent entertainment, 10 percent information--and the information without boring you." Despite many publishers' pretenses to the contrary, most working American journalists eventually accepted the basic validity of Hearst's philosophy. Many may still disagree with his percentages, but the vast majority came to realize that, like novelists, movie actors, recording artists, and professional athletes, journalists are pan and parcel of the entertainment industry.

As the age of print has given way to an age of electronic media and multimillion-dollar-a-year anchor personalities, this has become truer than ever.

* * *

Hearst wasn't the only publisher intent on reaping pan of the tabloid bonanza. Bernarr MacFadden, the flamboyant "king of physical culture" in the Roaring Twenties, was also intrigued by the runaway success of the Daily News . MacFadden had already discovered a publishing gold mine of his own with True Story magazine and other revealing periodicals, and he was eager for more.

In August 1922, MacFadden began testing the waters of the sensationalism market with an oversexed weekly magazine called Midnight . It featured large pictures of almost-naked women and verged so closely on obscenity that its staff expected to be carted off to the police station after its first issue. All photos used to illustrate articles were of curvy models in sensuous poses wearing nothing or next to nothing. Headlines on the cover included: "Sold to the Devil--A Desperate Man's Pact with Satan"; "From the Underworld to Fifth Avenue"; "Daughter of a Murderer"; "Last Call for Thrills"; and "Don't Monkey with the Women." There wasn't a word of troth anywhere in the publication. Every story was a total fabrication.

His worried editors pleaded with MacFadden to tone down Midnight 's content, but as the weeks passed, and circulation soared, it grew even steamier. "We're going ahead with Midnight exactly as she is," MacFadden said defiantly. "In a couple of months, we'll be up to the Saturday Evening Post , and that's a nickel magazine. We're a dime."

Before that could happen, however, an agent for the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice came calling at the Midnight offices, armed with summonses for the entire staff. He agreed not to serve them in exchange for MacFadden's pledge to cease publication immediately and destroy all copies of the issue that had just come off the press.

"They wouldn't dare do that to a newspaper because of freedom of the press," MacFadden told his associates a short time later. "Anyhow, we've learned something. Midnight was just a rehearsal for a magazine pattern we can apply to the daily field."

Two years later, in 1924, MacFadden proudly unveiled his new magazine-style daily, the New York Evening Graphic , with this promise to his readers: "We intend to interest you mightily. We intend to dramatize and sensationalize the news and some stories that are not news."

Even the photos in the Graphic were phony--"cosmographs," MacFadden called them. He used them for such purposes as showing the wife in a notorious celebrity, divorce case supposedly stripped to the waist in the courtroom, and the king of England scrubbing himself with a brush in the bathtub.

Some of its more diplomatic critics have described the Graphic as "the True Confessions of the newspaper world," but New Yorkers quickly found a more fitting nickname for MacFadden's blistering-hot creation. They called it the "Porno-Graphic," and with good reason.

Even today, more than seventy-five years later, the Graphic still represents the absolute nadir of daily journalism in America. And despite its founder's initial confidence, it proved a massive financial disaster for MacFadden. Advertisers shunned the Graphic like the plague, and even tabloid readers eventually reached their limit when it came to the amount of gutter-level make-believe they could stomach. By the time the paper died in 1932, after costing MacFadden millions in losses, it had few mourners. But while it lasted, it constituted the raunchiest daily peep-show the nation had ever seen.

The Mirror fared somewhat better, although it never turned a profit for Hearst. He sold it in 1928, was forced to take it back in 1930, then managed to bolster circulation by stealing celebrity columnist Walter Winchell away from the Graphic and basically turning the Mirror into a daily gossip sheet. (It seems appropriate that, after the Mirror folded in 1963, many of its expatriates--including its last managing editor--found a home at the National Enquirer .)

Among them, though, the Daily News, Mirror , and Graphic --along with other daily tabloids that sprang up in Los Angeles, Chicago, and other cities--kept the 1920s roaring with their brazen brand of "jazz journalism." They avidly followed the violent careers of such notorious gangsters as Al Capone, Dutch Schultz, and Legs Diamond, but their most blatantly sensational crime coverage was reserved for ordinary people caught up in lurid murder cases. For example, in November 1926, the Mirror claimed to have found "new evidence" in a four-year-old double slaying in which a respected minister, the Rev. Edward Hall, and his church's choir leader, Eleanor Mills, had been found shot to death on an abandoned New Jersey farm.

The deaths were originally ruled suicides, but because of the Mirror's relentless digging into the Hall-Mills case, the minister's grandmotherly widow and her two brothers were indicted for murder. More than two hundred reporters flocked to the small-town trial and filed more than 5 million words of copy from the scene. Unfortunately for the Mirror , the defendants were acquitted and later filed a libel suit against the tabloid. Such stories as the death of matinee idol Rudolph Valentino in 1926 and Charles Lindbergh's epic 1927 flight across the Atlantic were also milestones in the march of sensationalism.

These papers' insensitivity was matched only by their ingenuity. Case in point: In the spring of 1927, Mrs. Ruth Snyder and her corset-salesman boyfriend, Judd Gray, were convicted of killing Snyder's husband, and as Snyder's date with the electric chair neared, the rare spectacle of a woman being put to death sent the tabloid press into a feeding frenzy.

"Think of it!" blared the Graphic the day before the execution. "A woman's final thoughts just before she is clutched in the deadly snare that sears and burns and FRIES AND KILLS! Her very last words! Exclusively in tomorrow's Graphic ."

But the Daily News upstaged the Graphic and stunned even hardened tabloid readers the next day with a riveting front-page photo, obtained secretly by a staff photographer with a miniature camera strapped to his ankle, of Snyder being electrocuted in the death chamber at Sing Sing Penitentiary. The picture was made at the instant the current surged through her body.

Not coincidentally, it was during this same period that a former Hearst advertising executive named William Griffin began publishing a new full-sized Sunday newspaper in New York. Although its birth received little fanfare in a city with a dozen other, much larger papers, the newcomer was bankrolled by Hearst, who used it as a sort of testing ground for new ideas. It's been said that the best of these ideas were usually adopted by Hearst's mass-circulation dailies, while the worst ones, unfortunately, often lingered at their point of origin.

The paper was called the New York Enquirer , and over the next quarter-century, it was destined to go through a series of less-than-impressive incarnations. In the 1930s, it adopted a pro-Nazi tone and espoused the cause of German-American unity. During World War II, it virtually vanished, then reemerged as a "sports paper" heavy on racing news and betting lines.

By 1952, when it was purchased by a young MIT graduate named Generoso Pope Jr., its circulation had dwindled to less than 17,000 and it had become, in Pope's own words, a "dumping ground for publicity agents and columnists who wrote for free and couldn't get their stuff printed anywhere else."

One of the first major alterations Pope made to his property was to scrap its traditional eight-column format and turn it into a tabloid. Chances are, it seemed like a small step at the time--perhaps just an attempt to give a worn-out perennial loser a bit of a facelift--but it proved to be a momentous change.

At the time, no one other than Pope himself could possibly have imagined that such an obscure little paper would become America's first national tabloid, much less that it would grow into the largest-selling weekly publication in the country. No one would have guessed that it would one day rank among the ten most profitable single items in the nation's supermarkets.

And certainly, no one would have dreamed that this ragtag sheet, along with the flock of imitators it inspired, would permanently change the way Americans relate to their news and newsmakers.

But it did. It did all that and more.

The evolution of sensationalism was about to take yet another major step, and America was about to discover a brand-new descriptive term for the most gut-wrenching brand of shock and horror.

It was, of course, the National Enquirer .

Copyright © 2001 Bill Sloan. All rights reserved.