The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

Chapter One

July 21, 1998

A perfect midsummer day in Vermont, the world in full leaf, sunny but with a fair breeze. Ideal for the last driving clinic before the gala three-day carriage-driving show this coming weekend. About a dozen of us, including two pairs--carriages drawn by matched horses--are warming up on a large grassy area enclosed by a fence on one long side, buildings on another. A stone wall at the top of the field divides it from the state road. We're going to practice driving figures for the dressage phase of the show. Just as ice skaters have certain patterns they must execute in competition, carriage drivers also must demonstrate patterns including circles, serpentines, changes of direction and pace, good square halts, and backing up in straight lines.

There are two new horses here today; they look like young Arabians with their pretty little dished profiles. It's going to be a nuisance to integrate them into our already cohesive group. The owners put one in a stall and hitch the other to drive. The stabled horse whinnies frantically when his buddy leaves. Then he leaps up over the four-foot dutch door and races out onto the field, where we're all intently moving on our own, concentrating on getting our horses limber and balanced before the formal session with our driving instructor begins.

Although they've never met before, the loose horse makes a beeline for my horse Deuter, perhaps attracted by his bright red chestnut color, and runs into him head on. I feel Deuter jitter and suck back behind the bit. Is he going to rear and then plunge forward to escape?

"Easy, Dude," I tell him. "Eas-ay, eas-ay," words he knows but doesn't always honor.

Finally, one of the owners runs out with a lead shank and captures the little loose horse. Crisis past, Deuter seems to relax in my hands. He rounds over nicely on the bit, and comes across the diagonal at an extended trot, a little overeager but presumably none the worse for the encounter.

"Talk about déjà vu all over again," the instructor says as we come past her. "That was quite a flashback he had. Some things they never forget." She's a highly regarded woman in the horse world, not only as a trainer and driver but also for what I call horse charisma, her ability to "read" an animal from the way he is moving and responding.

I agree with her as we trot past. "He almost lost it there but I think he's over it," I say, and we cross the field once more out of her line of sight. The very first time we hitched him at this same facility, he was run into by a bridleless horse still attached to his cart. (Taking the bridle off before detaching the horse from the carriage is a breach of etiquette serious enough to get the miscreant disbarred.) Luckily, Deuter was safely out of the shafts at the time, but he fled in terror from the assault and ran two miles up a steep dirt road before the groom on a coach-and-four that was coming down the hill jumped off and retrieved him.

For at least a year Deuter became restive whenever another rig came toward him, particularly if the carriage was drawn by a pair of horses, with the attendant extra rattle and banging sounds. Now, though, he feels like his old self. My navigator, who has been riding on the back step of the carriage, dismounts and joins a group of observers on the sidelines.

Then, as we come to the top of the field along the stone wall, an immense piggyback logging truck roars up behind us, its multiple chains making a considerable racket.

Without warning, Deuter shifts out of his soft floating trot into a gallop. It takes me about three seconds to realize what he's done; I keep thinking he'll come back into my hands in another stride or two. We tear around one corner by the buildings and he bounces me out of my seat. I struggle to regain my balance and finally find the brake with my right foot, but even with all my weight on it, the mechanism is powerless to slow him down. There are all those carriages to steer around. I don't dare bail out. What if he runs into someone?

The carriage that I'm driving is a four-wheel metal marathon vehicle with a wedge seat that is supposed to hold the driver, or "whip, "securely in place. There's a stand on the rear for the navigator, or "groom," who accompanies the driver during the marathon phase of a driving show; the whole rig weighs about 350 pounds.

For the accident itself I have total amnesia. I come back to consciousness facedown, arms and legs asprawl. My limbs are numb, I am only vaguely aware they are still attached to me. Kathy, an old carriage-driving buddy who happens to be an emergency room nurse, is kneeling beside me, keeping me absolutely immobile. It is she who saves my life.

I gasp, "I can't breathe," and she comforts me. "Yes, you can. Just keep taking little sips of air."

Before the helicopter comes, before it swoops down beside me, the menacing roar of its rotors rousing me momentarily, I fade in and out of consciousness. Troughs and swells of pain suck me down, then spit me out. They roll me over and over, a pebble caught in this ocean where time has no limits and agony is without beginning or end....

* * *

The helicopter lands on its tidy pad just outside the Trauma Center. I remember only fleeting moments of this experience -- the terrible jolts of my stretcher being loaded and unloaded, the unspeakable, all-over pain. Victor, my husband, tells me they worked on me in the Trauma Center for about five hours while he sat in the waiting room. The doctors came and went every half hour with further news--of my punctured lung, of multiple broken ribs, of internal bleeding, and bruised kidney and liver, and loss of neurological function. "Oh my God, oh my God," was all he could say at each notification, this man who is seldom at a loss for words.

July 22

Imagine a bird cage big enough for a large squawking parrot. Nothing fancy; no rococo bars with curlicues at the top, just a sturdy cage fashioned from titanium and graphite, but missing a few bars front and back. Imagine a human head inside the cage fastened by four titanium pins that dig into the skull. The pins are as sharp as ice picks. I wake up in this cage, disoriented, desperate, sicker than I have ever been. No feeling in my arms or legs, but a vague sense that my head is entrapped forever. No movement left or right, up or down. I am a stationary parrot inside my strict cage.

* * *

Some orthopedic wag dubbed this form of axial traction a halo. First applied in 1959, it was attached to a rigid full-body cast and was used to immobilize paralyzed polio patients whose airways were in danger because they could not hold their heads upright. Later, its usage extended to postop patients with cervical spine injuries, tumor removals, and congenital spinal malformations. The early halos, weighing upwards of ten pounds, were made of metal, which was opaque to X ray and was not MRI or CT scan compatible. Modern halos are made of lightweight composites. The full-body cast has given way to an adjustable plastic vest and the metal uprights of the cage are made of anodized metals so that they don't "seize" during tightening. Knurled bars are designed to prevent slipping; the entire halo must remain structurally intact.

Ancient Hindu epics report that Lord Krishna corrected the hunchback of one of his devotees using a similar device. What it was attached to is not recorded. In the modern version, the one-piece plastic vest is cut low enough in front to accommodate a woman's breasts, and is solid in back except for an opening for the spinal column. The vest fastens securely at the waist with thumbscrew fasteners spaced two inches apart. The instructions that come with the synthetic sheepskin liner caution against ever removing it. (It is, however, removable and replaceable after a shower or a workout in the therapy pool, neither of which I am permitted.)

The halo pins are still being redesigned. The exposed ends are secured with locknuts, and a little wrench is attached to the lower part of the cage, presumably to undo it in emergencies. The places where the picks grind into the cranium are euphemistically called pin sites. They must be kept clean by swabbing them twice a day with hydrogen peroxide in a normal saline solution.

I read that the "broad-shouldered pointed pin" is giving way to "a broad-shoulder pin with a bullet-shaped point" to make better contact with the skull and ensure "more rigidity at pin-bone interface." I read with a certain horrified fascination that the pins must be placed over the thicker portions of the skull--it had never occurred to me that there were thicker and thinner portions--so that the skull itself is not punctured. It follows that the pressure of the pins has to be applied correctly to get maximum fixation without breaking through the cranium. When the correct position for the pins has been determined, it takes a team of two using a torque wrench to tighten the pins by half turns at a time on opposite sides until the proper pressures--six pounds of torque--are reached. (Torque wrenches are calibrated to a certain force which cannot be exceeded; one need not be a physicist measuring force times distance to arrive at the appropriate measurement.) The front pins are placed on the forehead; the rear ones below the equator of the skull, which I take to be the greatest circumference of the head in question.

There are a number of caveats when it comes to pin placement: if a pin impacts the temporalis muscle, the patient may not only be in pain, he/she may not be able to chew. A pin inserted at the temporal bone may penetrate the thin layer there. The supraorbital nerve and frontal sinus are to be avoided. There are also issues of pin migration, which may dislocate the halo crown itself, and pin-site infection, which could endanger the whole process of restraint. (I was either unconscious or very heavily drugged when my pins were inserted; I am grateful to learn about these pitfalls after the fact.)

Applying the vest involves logrolling the patient, with support, so that the back shell of the vest can be slipped into place, then laying the patient supine to fit the front vest. The uprights of the cage must be evenly spaced on either side of the patient's head, the lateral bars connected to the uprights and to the halo and all bolts tightened to the proper torque--thirty feet/pounds for an adult. Fitting a child is dicier, as the young skull is thinner and may require more pins at a lower torque.

The medical articles that I have scanned stress how important it is to maintain communication between patient and physician. The patient should be informed of possible side effects and signs of problems. In my case, there was no such communication. I am glad I did not know that if a loose pin required more than two turns of the wrench to tighten, a new pin should be inserted in an adjacent site and the old pin removed. Nor was I aware that patients with foreheads that slope at a strong angle and patients with highly developed shoulder muscles, such as weight lifters, may require an extra pin behind each ear. Neither of these applied to me. I was uncomfortably familiar with pressure sores developing under the vest, with contact dermatitis and sweat rashes, and, most of all, with muscle tightness when lying down, for which the palliative of a small towel used as a neck roll provided little relief.

I am also glad I did not know that the halo does not totally inhibit motion of the vertebrae and that the most motion occurs when the patient goes from supine to upright or vice versa. In one study the overall motion measured was almost one third of normal range of motion; nevertheless, healing under this condition can take place.

Thousands of people are confined in halo restraints in the United States and Europe every year. At least ten companies are manufacturing these devices in the U.S. alone. Gradually I meet others of my kind, doggedly slogging around under the burden of our equipment, some tipped slightly forward, some tipped slightly back, to compensate for the neck fractures that landed us in this predicament in the first place.

I don't remember, or choose to remember, much about how I got here. It was Kathy who stabilized my head for almost an hour as I lay paralyzed on the field, Kathy who sent someone to call the rescue squad and who lobbied, once they arrived, for them to call in the Medivac team. Getting a helicopter takes protocol in this rural area, but once it was on the ground beside me, only six or eight minutes elapsed before I was airlifted to a local major medical center. I remember coming to and begging for painkillers en route, which the team is not permitted to administer. I remember kind strangers calling me "honey" and "sweetheart" and how this intimacy surprised me. I did not know then that they were afraid I would not survive the trip.

The vertebrae I broke are at the very top of the spinal column: C1, which is ring-shaped and fits around the odontoid, C2, which looks rather like a thumb. In the trade, one form of C2 break is known as the hangman's fracture, because the same vertebra is snapped when the trapdoor opens under the gallows. Mine, I learn long after the fact, is a Type II fracture, located in the narrowest region of the odontoid, the "waist" of the thumb.

Things are coming back to me little by little, but I am stuffing them down in a dirty laundry bag to be reviewed and shaken out later, when I get my courage back. I realize from the outset, though, that I've lost all feeling in all four limbs, and I think at that moment I'd rather be dead. In fact, thinking about being dead absorbs a lot of my energy these first days. While I am pinioned flat on my back, I am almost as black and blue with grief and guilt for causing anguish to my family as is my torn body. I have two black eyes and a large contusion on my right cheekbone. My whole right side is purple, shoulder and arm especially brilliant. Apparently I have also punctured a lung, broken eleven ribs, braised a kidney and my liver, and suffered considerable internal bleeding. I've been given two units of packed red blood cells. There's an IV line in the vein below my right shoulder supplying me with morphine and glucose and an oxygen tank feeds the tubes in my nostrils. These accompany me as I am wheeled from CT scan to angiogram to MRI.

(Later, I learn from my medical records, which I devour with hungry voyeurism, that I occasionally came to and spoke clearly while the paramedics applied a cervical spine board and turned me over, like an immense beetle specimen, for transport. From my husband Victor's E-mails to family and friends, I further learn how many people were pulling for me from the outset. His communiqués are detailed and invariably upbeat, even in the first worst days: "Max's eye blink responses have indicated alertness and she has begun to whisper-talk with the breathing tube out. Breathing gets better by the hour. Hematomas are receding. She's a REAL fighter which is of course why I wanted to marry her!")

I plead guilty to being a jock. I've been a jock all my life, from my adolescent days working out in the Broadmoor Pool in Philadelphia racing freestyle for the Women's Athletic Association, to my lengthy stint as a water safety instructor at summer camp. Horses, which had always been my passion, came back into my life when my daughter Judith was nine and caught the fever. It didn't take long to infect Victor as well. By then we had moved to the New Hampshire farm and were immersed in livestock. For more than a decade Victor and I travelled together as competitive trail riders on horses we had bred and midwifed and cared for, logging literally thousands of miles to condition our horses for the long rides.

Competitive trail rides and/or drives, over distances that range from twenty-five to one hundred miles, typically involve forty to fifty horses departing at one-minute intervals to complete a prescribed course within an ideal time. This is not a race. Every equine starts with a perfect score of 100. Points are deducted for fatigue, virtually imperceptible lamenesses, and pulse and respiration in excess of the parameters for that day, which are based on temperature, humidity, and so on. The horses are subjected to very thorough veterinary checks before they leave; along the way they are observed by the judges. At a midpoint they are held for several minutes while their pulse and respiration are taken and dehydration tests are performed. After the ride or drive, they undergo even more rigorous checks. The winning horse is the one in the best condition. With a score in the high 90s, he will look, after, say, fifty miles, as if he had not yet left the barn.

The horse who almost killed me is seventeen. His mother was a Standardbred who had failed at the track and fallen on bad times. We took her out of a deplorable situation one bitter January day, and trailered her down to Princeton, where I was to teach for a semester in the creative writing program. The mare, then a four-year-old, had been confined for months in a space barely big enough to turn around in. Her front hooves had grown out and around her shoes. She had lost so much muscle tone that her body felt like an immense Jell-O mold. Once in Holmdel, New Jersey, in a forty-acre field shared with several Welsh ponies, she relearned how to gallop and cavort. At the end of the term we returned to New Hampshire to begin her career as a distance horse under saddle.

I soon discovered her fatal flaw. In a group of horses dispatched at one-minute intervals she became increasingly agitated, indeed uncontrollable from the saddle. "If you'd a' breathed on her belly she'd a' gone over," an equestrian friend remarked, observing her rearing in place. I learned not to put my toe in the stirrup until my number was called. Then, as she felt me shift my weight, bringing my right leg down on her right side, we would set out at the ground-eating trot Standardbreds are famous for.

The mare's name was Genesis. Her firstborn son we called Deuteronomy, Deuter, or The Dude for short. I was the first thing he saw when he slipped out of his mother. He stood almost immediately that cold March night, a wide-eyed and stiff-legged chestnut with a white star and two white hind socks. Although he grew into his head and ears, at that moment he looked like a miniature draft horse.

Privileged from the outset, he was easy to live with and easy to train. He bonded with humans, invariably whinnying back when either of us went out to the pasture to call him. Our only gelding, he observed his place in the pack, deferring always to the imperious mares, and casually accepted the company of our dogs, who often travelled at his heels. He only took offense when the youngest, a little white foundling mutt, would squirm into a culvert on one side of the road and emerge from it on the other as we trotted by; this called for a vigorous sidestep and a little grunt before Deuter recovered his composure.

He loved distance work, attacked the hills of New England as if they were mere hummocks, and was comfortable in a group of horses. Horse people in general liked his agreeable nature and sturdy build. They said things like, "He has a very large motor in the hind end," and "Well, he's a little over-endowed in the ears department but he sure can cover ground." He was the horse I had waited for all my life.

By the time he was about ten, arthritis was making long hours in the saddle painful for me and I reluctantly switched from riding horses to driving them. We began with a lightweight two-seater phaeton made of ash. Because of our hilly terrain we had a hydraulic brake installed so that the driver could hold the weight of the cart back from the horse's hind end while going downhill, a great boon in distance work. A little later, we acquired a small sleigh, a replica of the famous Portland cutter once used by rural doctors to make their rounds in winter.

All four of our horses made the transition from working under saddle to going in harness, some more readily than others. Our youngest, a three-quarters Arabian mare of impeccable bloodlines, spent the better part of her fourth year protesting that shafts must never touch her sides, but eventually grew into a very correct driving horse.

The genes from his Arabian sire combined with his Standardbred half to make The Dude a natural harness horse. He could travel all day at a steady open trot without apparent effort. On woods roads he was sane and clever about negotiating the twists and turns. Out on asphalt he was never entirely relaxed but gradually learned to put up with traffic whizzing past. We brought home some blue ribbons--typically, driving event ribbons are long and flowing affairs--and proudly hung them in the living room, temporarily obliterating two pen-and-ink drawings by Boston artist friends, Harold Tovich and Barbara Swan. Barbara's are the originals of pen-and-ink drawings she had done to accompany some of the poems in my collection, Up Country , which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1973.

We also attended some sleigh rallies and then moved on to combined-driving events, where obedience, speed, and lightness and ease of movement are key requisites. Deuter had incurred a strained ligament on the final stretch of the hundred-mile drive and I felt that he needed a break from distance work. In combined driving he enlarged his vocabulary to embrace several new verbal commands: "slow trot," "working," "trot on," "back," and "come up." Because he was so responsive to my voice, he scored well in dressage.

In addition to dressage, the other two phases of a combined-driving show involve weaving between an often tricky obstacle course of cones in correct numerical order without dislodging any of the tennis balls perched atop the cones, and traversing a marathon that typically concludes with five to seven "hazards." Deeming this term too fraught with danger, the American Driving Society seeks to replace it with the word "obstacle," but among drivers, hazard is the common word still. Hazards frequently involve crossing brooks and streams, covered or other bridges, and making tight turns up and down hill as well.

We had now reached a level of competition in which my two-seater phaeton was no longer safe. It's a road cart, great on the straightaway, but tippy on the slant. At this juncture, I bought the marathon four-wheeler. The navigator on the rear step provides ballast for the carriage as it swings around sharp corners, negotiating the hazards at a speed commensurate with the whip's and the horse's ability. For three halcyon seasons with this vehicle I worked hard to improve my driving skills and bring Deuter to ever-higher levels of performance. My navigator and I went to clinics and horse trials; we trailered north and south to adjoining states. Still a jock, I was so caught up in the competitive driving world that I turned down all summer poetry seminar and reading options between May 1 and October 1. My hubris knew no bounds. If only it had been otherwise! If only some Cassandra had whispered in my ear.

(Continues...)

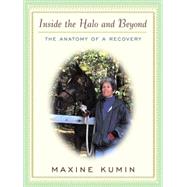

Copyright © 2000 Maxine Kumin. All rights reserved.