Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

| Foreword | xi | ||||

|

|||||

|

1 | (28) | |||

|

29 | (24) | |||

|

53 | (18) | |||

|

71 | (14) | |||

|

85 | (16) | |||

|

101 | (18) | |||

|

119 | (26) | |||

|

145 | (14) | |||

|

159 | (20) | |||

|

179 | (22) | |||

|

201 | (8) | |||

|

209 | (18) | |||

|

227 |

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

After I moved to Illinois, my sister and I wrote to each other once a year, if that, and neither of us liked to talk long-distance. We were happier apart. I could never see Julie, or hear her voice, without becoming at some point, then or later, aware of our drab and banal defeat. I had married an ungenerous woman; Julie, a big good-looking fool. I had started out to be a surgeon and ended up a druggist; and Julie, who had too much beauty and arrogance and wit for any single ambition, never even left home. She had planned to be a world rover-an artist, if she had the talent; an adventuress, if she didn't-and in the end she never, literally never, lived anywhere but in the house where we were born.

No matter what we talked about, all we ever really said was, Here we are. This is how we turned out. And she never offered us the comfort of a shrug, the summing up and laying to rest of a sigh. She never accepted it, or even complained, which would have been at least a kind of acceptance. Seeing her always produced a delayed disturbance in me, an obscure panic.

"She depresses you," observed my wife, who thought Julie cold and critical, and chose to believe that I, not she, was jealous of Julie's money, her "business acumen." This was absurd, but so was the truth: Julie always made me feel that time had not quite run out for us, that I only had to do some simple, obvious thing and everything would be all right. I didn't know if the feeling came from Julie or from me, or which of us I was supposed to save, and from what. The future, vague and sad, did not frighten me half as much as knowing that it was not carved in stone.

She didn't dote on her children, it's true. They'll make hay out of that. She was a competent mother, when I still knew her, and she often scolded me for not having kids myself, but she let Samson do the doting, the clowning. Samson was the one who made faces and talked baby talk. "He's so good at it," she said.

She treated him with an affectionate contempt that suited him well. Their marriage, begun in heat like my own, had become an antiseptic partnership, amiable, frictionless, curiously graceful. She regarded all her losses squarely, with unforced humor and a perverse delight, as if at some ragtag parade of shabby miracles. She took none of it personally, not even the early loss of her beauty. "I am going to be," she once observed, "one of those barrel-chested women with stick legs." She made it sound like a caprice.

The last time I saw her we sat in her kitchen, our old kitchen, and her children played outside in the summer grass, and Samson puttered in the basement with his electronic kits, or ham radio, or whatever it was that year. Julie said, "Here's another one for the scrapbook. There was, until recently, an Australian crocodile hunter by the name of Basil Hubbard. Leguminous by name and, as it turned out, by nature as well. His widow-this was in Collier's -claims that all his life he was `obsessed' by the fear that a big croc was going to `get him.'" Julie grinned. "You're way ahead of me. Well, that's the beauty of this story.

"One day, while hunting, he sat down on a riverbank to eat his lunch and take a nap, which proved to be his last. Basil may have cursed his destiny, but he certainly didn't fight it. I picture him as a sort of cross between Hamlet and Mortimer Snerd. Anyway, in a couple of days they found his boots ... with his feet inside, hatch."

Julie had been collecting these stories since she was twelve. To qualify, the story had to be "All Too True," the title of her scrapbook. "They caught the croc, a behemoth with no tail, and Basil the Squash inside. Here's the wonderful part: this crocodile had been stalking him for months ." She hunched over the table and walked two fingers around the sugar bowl and pepper shaker in a figure eight. "They found the tracks of the Squash, some of them pretty old, leading up at last to his final resting place ... and right behind him, all the way, the unmistakable trail of You-Know-Who. Hah!"

"Captain Hook," I said. I couldn't laugh.

"Don't you love it!"

Well, no, I didn't. I didn't always have the stomach for the All Too True.

But I remember it now, and the red afternoon light on the kitchen table, and her children's voices outside the window. I remember, it all, in amazing detail, as my night plane whines toward Pennsylvania, and I am tempted, for one sickening minute, to give it significance . To make sense of the way my sister died.

And sure, how "wonderful," if she had been pregnant then, with the one who killed her. If, while she told about the crocodile, the Demon Baby had kicked out and bumped the table and given us a scare, so that later I could remember and add it to the list of things that make sense now, when you think about them, you know? But all the children she would ever have were playing outside in the yard.

Too bad for the storytellers. Too bad for the sense makers, the apologists, that nothing, then or ever, nothing was inevitable. It's just too bad.

* * *

I learned about my sister's death from a radio news report. My cashier, like the one before her, and the one before that, tunes in eight hours a day to our local all-news and information station. I hate what radio has become, and most of all these talk stations, with their constant hysterical updates. Why do we have to know these things? What are we supposed to do about them?

A kidnapped ambassador is heard on tape begging for his life. Forty thousand Soviet troops are put on battle alert. A fifth-grade class in Des Moines adopts an ailing zoo hippo. Record turnip unearthed in Greensboro. Bizarre double murder in Pennsylvania; children sleep through shotgun slaying of their parents. In Clarion, Pennsylvania. My home town.

I was filling Mrs. Holley's Librium prescription. Mrs. Holley is a pretty woman in her thirties, chubby like a doll. Mrs. Holley has had it. She comes in here with her full-length fox and orders refills of diet pills and tranquilizers and roams the aisles loading a wire basket with bath beads, tampons, bags of licorice and candy corn, boxes of Dots and nonpareils; tortoiseshell barrettes, panatelas, coloring books, Harlequins, and the New York Times . She spreads the evidence of her domestic life before me on the counter with a demure and wicked lopsided grin, and lets her coat fall open, flashing her pink flannel bathrobe. Mrs. Holley's grocer doesn't know what I know. Even her liquor dealer doesn't know her this well.

I love Mrs. Holley and would take her home with me, and punish her, and comfort her, if I were not myself so tired and old and incompetent. I was thinking of this, of poor timing and lost opportunity, of sad clues and hopeless mysteries, while Mrs. Holley, clowning sweetly, waved the empty Librium container in my face like a lacy handkerchief, telling me as always to "Fill her up," and smiling her smile, when the news came over the radio that Julie was dead.

* * *

When she heard about Julie, my wife drove all the way from Urbana, and let herself into my apartment with a key I forgot she had. She was there when I got home. Coffee was brewing and my old suitcase was open on the bed and half-packed. She had already booked my flight to Pittsburgh. When I walked in she just hugged me; and her ruined hair, clipped and brittle and bottle-red, held a trace of its old clean perfume. For a while she sat beside me on the couch and massaged the muscles of my neck and shoulders while I leaned forward, elbows on knees, and my hands, long and white like my father's, dangled pointing at the floor. When my eyes filled it was not for Julie, not yet, but for my wife and our failure and the astonishing fact of her kindness at this time.

But then she said, "I don't know why, but I'm not surprised. She was a bitter woman. You refused to see it." And I said, "You're not surprised that my sister was murdered? You're not surprised ?" She said she had called the Petersons, old neighbors in Clarion, and gotten "the inside story" from them. As she related the details her voice revealed, despite itself-for my wife is not a bad person, no worse than I-a mean excitement, and she drew out her tale for maximum shock effect, saving until last the horrendous and apparently well-founded suspicions of the police. As I listened, at the dead center of my horror and disbelief I felt ashamed of her and sorry for the silly woman she had become. She ran with me once, right beside me, matching stride for stride, down a clean white stretch of the Atlantic coast in early morning; and her hair was long and gold.

* * *

According to the papers, Samson Willoughby died on his feet, in the doorway to his wife's room, shot twice in his chest with his own shotgun. They say Julie died in bed. "As she slept." She was shot just once, point-blank, in the back of the head.

The three children, ages twelve to sixteen, said they heard no shots, but woke up in the morning to find the living room in disarray, their father's safe open and ransacked, the clock overturned and broken at some early morning hour. They found their parents, and the daughter, Samantha, four years old when I saw her last, called the police.

Their story made no sense. Even small-town police could tell there were no intruders, no robbery. Every piece of evidence, beginning with the temperature of the bodies, argued otherwise. The bodies were too cold. I'll remember that. The rest of it-tire tracks, deadbolts, broken windows-could not possibly matter less to me. Julie's children should have been more clever. When challenged, they turned sullen and briefly silent. They swiveled their heads toward one another and blinked like owls.

"The Willoughbys were not a close family," says an anonymous neighbor; "Looking back you could see it coming"; and I honestly wonder if the papers don't invent these people. (Julie would have clipped this for the All Too True and pasted it beside that old yellow photograph from the Clarion Call of a horse-faced woman in a straw hat captioned PAINFULLY INJURED. She was twelve when she cut that one out.) Another Solomon reports that Julie and Samson were "workaholics," whatever the hell that means, and seldom home, and "the kids ran wild." So naturally. "Drugs." Michael and Samantha, the older two, were often "spaced out." Therefore.

Mr. Peterson is quoted in the Sunday Tribune , and bless his sensible old soul. "They were strangers," he says. "They came and went like strangers. There's a lot of families like that now."

But everywhere they display the same picture of Julie the Real Estate Woman, heavy, hard-eyed, thin-lipped, vulgar, her terrible professional smile framed by deep crescents of discontent; her regulation helmet of brassy hair. A face I have never seen and will never accept. A photographer's trick; falsified evidence, for the storytellers. Here is a fitting subject for cheap tragedy. These are the women whom their young must turn on and devour.

* * *

I'm staying at the Petersons', waiting for the funeral. I can see the old house from my bedroom window. Julie had it painted tan, or beige, or camel, one of those new colors you can't remember from one time to the next. The grounds are landscaped now. It looks like someone lifted up the house and unrolled the grass beneath it. There are flower beds and fruit trees set out on the green like furniture. Out back all that's left of the woods where Father took his long walks are a few birch trees, to mark where the next property, the next lawn, begins. I didn't know she'd sold the woods.

Yesterday a gardener came and worked on the rose garden in the backyard, a perfect square with sunburst gravel paths and a sundial and a birdbath; where once there was a smaller, shapeless plot of dirt, dug and planned and turned by children, that summer we tried to grow tomatoes and I used to pick green hornworms off the leaves and throw them onto the roof for the birds to eat.

Mrs. Peterson caught me watching the gardener, and she said, "The inside's all changed around, too. You wouldn't know it." Somehow she knew she was comforting me.

It's the Murder House now, and the neighborhood kids are going to want to believe that it's haunted. But it isn't. I can tell that from here. It really was once, haunted, by living children. I wonder if Julie exorcised our ghosts before she died; if in her lifetime she ever stopped running into the ghosts of those children whose kingdom this had been. All I know is, now the house is truly quiet, now that she is gone.

The night before the funeral I sit up with Mr. Peterson and we drink Iron City in the rumpus room, where the electric trains used to be, and stare at the black screen of his old RCA TV. He tells me all he knows. I can stand to hear this much, and only this much, and only from him. He knew us when we were children.

Samantha and Michael planned to rob the house and steal Julie's Mercedes. They were going to run away and they needed money for drugs to sell, in New York City, or Timbuktu. Samson had an old-fashioned safe in his basement office, and when they discovered the combination they set their plan in motion: a complicated, romantic thing involving sunglasses, wigs, and phases of the moon. They could have ripped their parents off in the daytime, when they were out. But this wouldn't have been as much fun.

Mr. Peterson shakes his head. "All I can tell you is what Larry told us," he repeats. Mr. Peterson's youngest son is a reporter for the Clarion Call . "The police kept asking the kids, `But why take risks when you didn't need to?' They were trying to make sense out of it, you know. And you know what Samantha said? Something like, `It made a better movie this way.' A better movie! And they asked her, `Were you planning to make a movie? What are you talking about?' But she just laughed at them and said, `Yes, that's right, we were going to Hollywood to make a movie!' She said the cops were stupid. She said, `Don't worry about it. There's no way you could ever understand us.' You know, the way kids do." Mr. Peterson sips his beer. "Although, I think maybe she was right about that.

Continue...

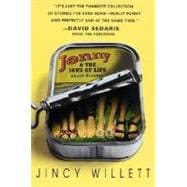

Excerpted from JENNY AND THE JAWS OF LIFE by Jincy Willett Copyright © 1987 by Jincy Willett

Excerpted by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.