Note: Supplemental materials are not guaranteed with Rental or Used book purchases.

Purchase Benefits

What is included with this book?

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

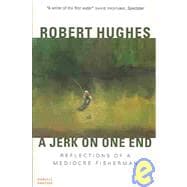

Excerpt

Most fish become familiar if you go after them regularly. Yet not completely so, for each fish is new, and there are moments when the sense of strangeness revives and sits bolt upright; these are among the high points of any fisher's career. The one I remember most vividly happened off Montauk, at the eastern tip of Long Island, in the summer of 1985. I was on an overnight trip to fish for tuna on the Canyon, a part of the continental shelf about seventy miles out in the Atlantic, in a no-frills offshore boat skippered by an artist friend, Alan Shields. After the long night's run out, the sun rose golden and glorious out of the Atlantic and the sea was flat calm; you could see the smallest ripple a mile away. We set the trolling lines and the "bird," a teaser with two wings that fluttered on the surface sixty feet back from the stern and was supposed to excite the curiosity of fish. That done, there was nothing to do but wait. An hour later, nothing had come up. And then Alan saw something dead ahead: the unmistakable sickle fins of two giant bluefin tuna, hovering on the light-stricken surface as though sunning themselves. They were perhaps half a mile ahead. If we went past them at trolling speed, we would scare them down. There was probably no way of get-ting them to strike at a lure. But Alan wanted one of those fish (at the prices the Japanese were paying dockside at Montauk for prime bluefin, he could have paid for a whole season's fuel with it), and he decided to go after them with a harpoon. He would steer the boat and I would be up in the bow with the spear, whose detachable bronze head was already rigged to several hundred feet of line and an orange balloon buoy. There I would stand, intrepidly balanced out on the bow pulpit, as we treacherously sneaked up on the fish, and when I was within range, I would fling the harpoon into the tuna's vitals. There was only one snag about this arrangement. I am not Queequeg. My only experience of spearing fish was sniggling eels with a small trident. Of hitting a tuna from above with a ten-foot spear, I had no conception, and the fact that fishermen used to do this as a matter of course in their pursuit of tuna, swordfish, and other monsters of the deep off Montauk meant very little to me. I was a rank novice, a mere art critic, and (worse) an art critic who had read several cautionary yarns of what happens to incautious harpooners who happen by accident to get a coil of line around their arm, leg, or even neck as it comes burning out of the tub, pulled by a quarter-ton of potential sashimi, maddened with shock and pain, accelerating down and away into the oceanic abyss. Tuna can do sixty miles an hour. This thought hung before me as I drew closer to the fish, nervously balancing the shaft in my hand. I focused on the nearer fish. It seemed to hover in the water: the silver flanks, the dark blue back, not the leaden darkness of a dead fish, but alive, inexpressibly vital, the small dorsal finlets glowing yellow. Closer and closer. And then I caught its eye, that huge eye with its hypnotic black center, evolved to capture every last photon in the deep sea. God, it occurred to me, was looking at me through that fish. I was frozen. Dimly I heard a voice from the flying bridge behind me: "Stick him! Stick him!" But I couldn't; I couldn't imagine throwing the harpoon. The eye had paralyzed me. Later I would learn from other fishermen, such as Peter Matthiessen, that this was not an uncommon occurrence. Never look at the tuna's eye, ran the conventional wisdom. Or at a swordfish's, either, which is even larger and more hypnotic. But I will never forget the sight of that bluefin, in the splendor of its unreflective life, or how it slid out of sight with the merest quiver of its body, cleanly accelerating through the blue, gone forever. It took Alan some time to forgive me.

Copyright © 1999 Robert Hughes. All rights reserved.