LEON HENDRIX lives in Los Angeles and is pursuing his art and music full-time in the Leon Hendrix Band. In addition to touring across North America and Europe, he is also the owner of Rockin Artwork LLC, a company that licenses Jimi Hendrix’s likeness and image.

ADAM MITCHELL is also the author of Street Player: My Chicago Story with legendary drummer Danny Seraphine. He lives in Los Angeles.

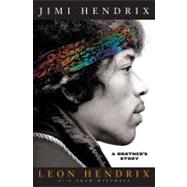

“His little brother Leon gives us ‘Buster,’ the Jimi Hendrix only his family knew. Keeping it real all the way, Leon Hendrix gives us an entirely new, life-size portrait of Jimi."—Joel Selvin, author of the classic Summer of Love and co-author of Sammy Hagar’s New York Times #1 bestseller Red: My Uncensored Life in Rock

The New copy of this book will include any supplemental materials advertised. Please check the title of the book to determine if it should include any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.

The Used, Rental and eBook copies of this book are not guaranteed to include any supplemental materials. Typically, only the book itself is included. This is true even if the title states it includes any access cards, study guides, lab manuals, CDs, etc.